By: Tyler Valeska, Michael Mills, Melissa Muse & Anna Whistler of the Cornell Law School First Amendment Clinic1The views represented herein reflect only those of the authors. They do not represent the institutional views of Cornell University, Cornell University Law School, or the Cornell First Amendment Clinic.

January 28, 2021

I. Executive Summary

The First Amendment’s protections for speech about government help form the nucleus of American democracy. Yet since President Donald Trump’s inauguration, the White House has sought to stem the flow of information that enables speech about its own inner workings. Deeply unsettling are the increasing attacks on the press and its most important sources—government employees. One method the White House is employing to cut off the link between journalists and sources is unprecedented: actively limiting current and former employees’ ability to speak about unclassified material through the use of nondisclosure agreements (“NDAs”).

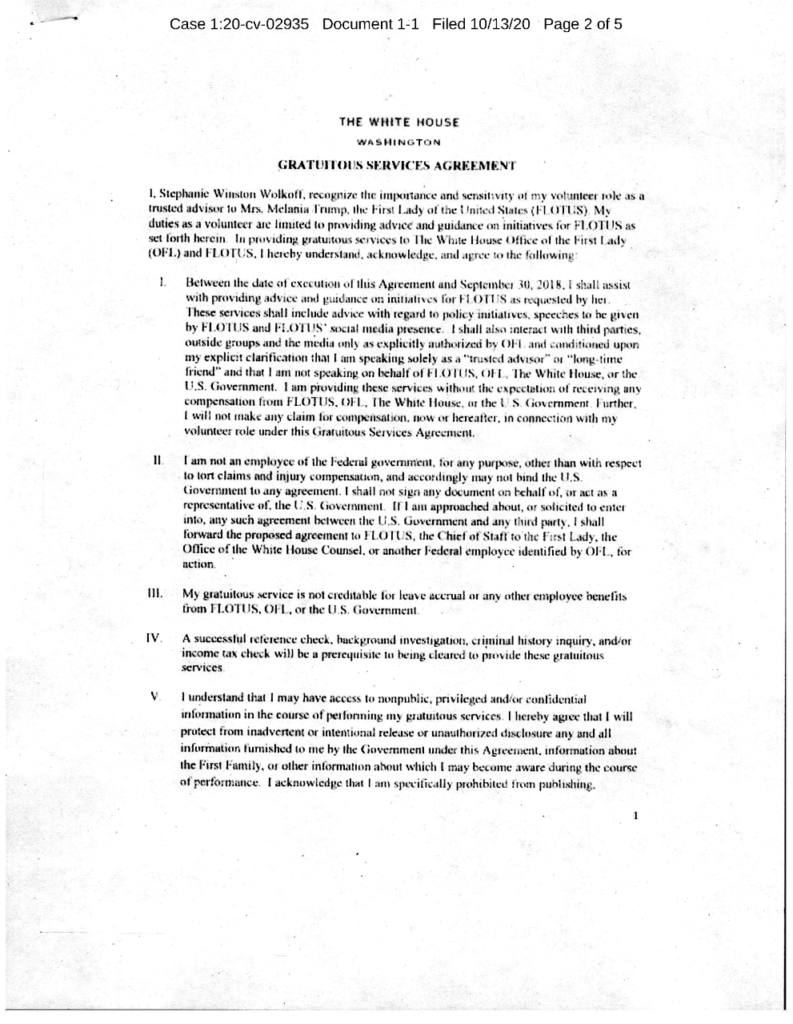

NDAs are commonplace in the corporate world and have been used in certain public sector contexts. But they have never been used to bar White House employees and aides from informing the people about daily happenings at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. Until recently. On October 13, 2020, the Department of Justice brought suit against Stephanie Winston Wolkoff, First Lady Melania Trump’s former unpaid aide. DOJ seeks to enforce—on behalf of the United States—an NDA Wolkoff signed, on White House stationary, as part of her agreement to work on a volunteer basis for the First Lady.

The terms of the White House NDAs far exceed the generally accepted bounds of public-employee speech restrictions. Their scope and vagueness swallow speech that is constitutionally protected; in effect, they prevent White House employees—and, by extension, the press—from speaking and reporting on matters of significant public interest. They thus infringe on the First Amendment rights of both government employees and the press.

Historically, the Executive has enjoyed great deference in administrative and managerial matters. It is this deference that makes the White House NDAs so concerning. If courts allow the NDAs to survive constitutional scrutiny, they could usher in a new era of heightened speech restrictions on those best positioned to inform the public about the inner workings of government. In this paper, we examine the history of NDAs, the government’s interests in enforcing them, and the First Amendment rights implicated by enforcement.

Relying on Supreme Court precedent, we identify the constitutional boundaries of speech restrictions for public employees and show why President Trump’s White House NDAs are likely unconstitutional.

A. President Trump’s Use of NDAs in the White House

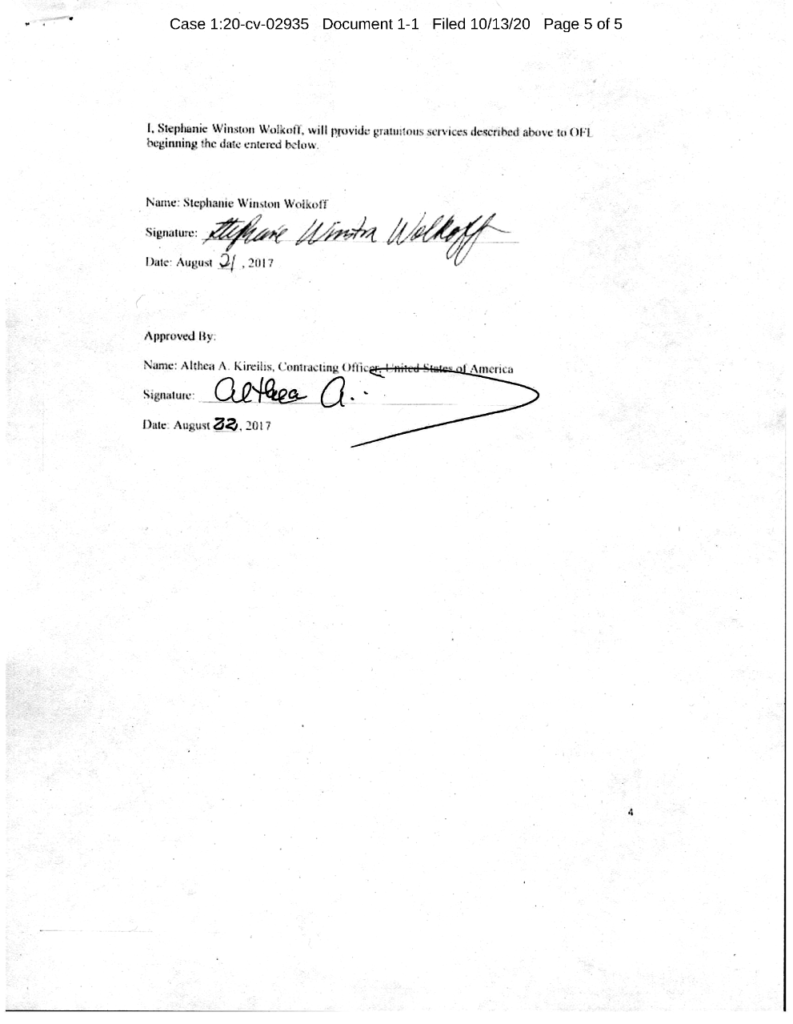

The Wolkoff case is the first time the Trump administration has sought to enforce a White House NDA, and the first time it has sought to enforce any information agreement for stated reasons entirely unrelated to the protection of classified information.2See Michael Schmidt, Justice Dept. Sues Ex-Aide Over Book about Melania Trump, N.Y. Times (Oct. 13, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/13/us/politics/stephanie-winston-wolkoff-justice-department.html. The Department of Justice (“DOJ”) is also currently seeking to enforce standard secrecy agreements against former National Security Advisor John Bolton based on his memoir published this past summer,3Michael Kranish, Trump Long Has Relied on Nondisclosure Deals to Prevent Criticism. That Strategy May be Unraveling., Wash. Post (Aug. 7, 2020, 6:00 AM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-nda-jessica-denson-lawsuit/2020/08/06/202fed1c-d5ad-11ea-b9b2-1ea733b97910_story.html. but unlike the White House NDAs, those agreements concern only classified information.4See infra Part II. Bolton did not sign a White House NDA.5Kranish, supra note 3. The Wolkoff suit focuses on a book Wolkoff published about her time volunteering for the First Lady.6Schmidt, supra note 2. DOJ brings claims against Wolkoff for breach of contract and fiduciary duty, based on unauthorized disclosure of nonpublic and confidential information, and seeks a constructive trust for all profits from her book.7Id. A DOJ spokesperson characterized Wolkoff’s White House NDA as “a contract with the United States and therefore enforceable by the United States.”8Id.

The Wolkoff agreement—attached as an exhibit to DOJ’s complaint—is the public’s first look at a White House NDA.9Government’s Exhibit A, United States v. Wolkoff, No. 20-2935 (D.D.C. filed Oct. 13, 2020) (hereinafter “Wolkoff NDA”). But much uncertainty remains. It is unclear who has been forced to sign White House NDAs and when. And we do not know the extent to which Wolkoff’s NDA—a gratuitous service agreement with the White House Office of the First Lady—differs in some ways from agreements paid White House employees signed. What we do know is that many employees, aides, and interns signed White House NDAs before and during their White House tenure.10Josh Dawsey & Ashley Parker, ‘Everyone Signed One’: Trump is Aggressive in His Use of Nondisclosure Agreements, Even in Government, Wash. Post (Aug. 13, 2018, 8:43 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/everyone-signed-one-trump-is-aggressive-in-his-use-of-nondisclosure-agreements-even-in-government/2018/08/13/9d0315ba-9f15-11e8-93e3-24d1703d2a7a_story.html. They began signing White House NDAs soon after Trump took office11Id. and continued to do so at least as late as 2019.12Asawin Suebsaeng, Trump White House is Forcing Interns to Sign NDAs and Threatening Them With Financial Ruin, Daily Beast (Feb. 21, 2019, 7:43 AM),https://www.thedailybeast.com/trump-white-house-is-forcing-interns-to-sign-ndas-and-threatening-them-with-financial-ruin.

Some initial uses were reactionary. In the midst of multiple early 2017 leaks, President Trump had senior White House staff members sign NDAs that reportedly mirror many of the terms found in Wolkoff NDA.13Dawsey & Parker, supra note 10.

They indefinitely prohibit staff from disclosing any confidential or nonpublic information to any person outside the White House without President Trump’s consent.14Id. As noted, this reporting is consistent with the terms of Wolkoff’s NDA. See infra Section II.I.

Former White House Counsel Donald McGahn reportedly convinced aides to sign the agreements after first refusing to draft or distribute them because he did not think they were enforceable.15Id. Former Chief of Staff Reince Priebus also allegedly pressured many leery senior staff members to sign.16Report: Trump Made White House Senior Staff Sign NDAs, Daily Beast (Mar. 19, 2018, 5:14 AM), https://www.thedailybeast.com/report-trump-made-white-house-senior-staff-sign-ndas.

In 2018, multiple current and former White House employees confirmed the administration’s use of White House NDAs. Former Press Secretary Sarah Sanders stated—inaccurately17Nancy Cook & Andrew Restuccia, Trump Tried to Ban Top Aides from Penning Tell-All Books, Politico (Aug. 13, 2018, 8:13 PM), https://www.politico.com/story/2018/08/13/white-house-staff-non-disclosure-agreements-books-776313 (citing lawyers and ethic experts for the premise that Trump’s White House NDAs have no modern precedent).—that “every administration prior to the Trump administration has had NDAs” and that “despite contrary opinion, it’s actually very normal.”18Jeremy Stahl, Is It Normal for White House Officials to Sign Nondisclosure Agreements?, Slate (Aug. 14, 2018, 10:23 PM), https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2018/08/trump-white-house-ndas-are-these-nondisclosure-agreements-normal.html (reviewing the historical precedent for NDAs in the White House compared to the Trump administrations’ use). Former White House counselor Kellyanne Conway argued that White House employees signed NDAs because they were needed to ensure privacy.19Julia Manchester, White House Spokesman: I’ve Never Seen an NDA in Trump White House, The Hill (Oct. 15, 2018), https://thehill.com/hilltv/rising/401908-white-house-spokesman-ive-never-seen-an-nda-the-trump-white-house. But assuming accounts are accurate, not all employees were forced to sign. Former Deputy Press Secretary Hogan Gidley, for example, told reporters that he never saw an NDA in the White House and was never asked to sign one.20Id.

Reports of White House NDA usage continued into 2019, when incoming White House interns were asked to sign agreements as part of their orientation.21Suebsaeng, supra note 12. The White House allegedly did not provide interns with their own copies of the agreements and characterized their required signing as an “ethics training.”22Id.

II. History of Governmental Use of NDAs/Suppression of Classified Information

A. Executive Secrecy Agreements

Past presidential candidates have used NDAs on the campaign trail and during the transitional period between presidential administrations; none have carried them over to the White House.23Orly Lobel, Trump’s Extreme NDAs, Atlantic (Mar. 4, 2019), https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/03/trumps-use-ndas-unprecedented/583984/ (explaining that the 2016 Clinton presidential campaign used NDAs); Cook & Restuccia, supra note 17 (noting that the use of NDAs for key political appointees in the White House is unprecedented). This practice is partially attributable to the widespread belief that NDAs restricting disclosure of unclassified information are not legally enforceable for government employees, who work for the people rather than any administration or officeholder.24Dawsey & Parker, supra note 10.

While the Trump White House NDA is unprecedented in its scope and duration, previous administrations have regulated the disclosure of information by executive branch employees.25Lobel, supra note 23.

Many presidents have availed themselves of executive privilege, the constitutional power that most closely approximates the use of White House NDAs. Executive privilege allows the president to keep information from other branches of government.26Mark J. Rozell, Executive Privilege and the Modern Presidents: In Nixon’s Shadow, 83 Minn. L. Rev. 1069, 1069 (1999). The privilege is properly asserted if it is determined that the protection of certain government communications is in the public interest.27U.S. v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683, 713–15 (1974) (Nixon I). It includes the deliberative process privilege, which protects “communications and documents evidencing the ‘predecisional’ considerations of agency officials.”28Todd Garvey, Presidential Claims of Executive Privilege: History, Law, Practice, and Recent Developments, at 20, Cong. Research Serv. (Dec. 15, 2014), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/secrecy/R42670.pdf. Confidentiality interests in the president’s internal communications with White House advisors, such as policy deliberations, have long been protected under this privilege.29See Memorandum for the Attorney General Re: Confidentiality of the Attorney General’s Communications in Counseling the President, 6 Op. O.L.C. 481, 484–90 (1982). Traditionally, presidents have asserted executive privilege by citing a combination of dteliberative process and national security needs, which often merit maximum protection.30Rozell, supra note 26, at 1071.

B. The Eisenhower and Nixon Administrations: Executive Privilege

The term “executive privilege” was coined during the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration,31Heidi Kitrosser, Secrecy and Separated Powers: Executive Privilege Revisited, 92. Iowa L. Rev. 489, 496 (2007). when President Eisenhower asserted it more than forty times.32Mark J. Rozell, The Law: Executive Privilege: Definition and Standards of Application, 29 Presidential Stud. Q. 918, 923 (1999); see also Congressional Testimony, Statement of Mark J. Rozell on the Presidential Records Act (Nov. 6, 2001), available at https://fas.org/sgp/congress/2001/110601_rozell.html. He believed that candid advice was necessary for executive branch deliberations, arguing that subjecting advisors to subpoenas by other branches would limit candor and, in turn, hurt the public interest.33Id. Eisenhower applied the privilege broadly. He invoked it on behalf of the entire executive branch, rather than just himself and senior White House officials.34Id. He went so far as to claim that all advice to the president—on matters public or private—was beyond the purview of disclosure requests by the other branches.35Id.

In response to this expansive approach, members of Congress sought to narrow the scope of executive privilege.36Id. Ironically, President Richard Nixon assisted in this effort after entering office, issuing standard procedures for when the privilege could be used—ostensibly to limit the power of the privilege.37Id. at 923–24. The standards Nixon introduced cabined invocation of executive privilege to “only the most compelling circumstances and after a rigorous inquiry into the actual need for its exercise.” Id. at 924. Nixon nonetheless later invoked the privilege multiple times during his presidency to hide incriminating information about his administration’s wrongdoings.38Rozell, supra note 26, at 1071. He argued that disclosing the incriminating materials violated the president’s “generalized interest in confidentiality.”39Nixon I, 418 U.S. at 713. The Watergate proceedings40Nixon’s use of executive privilege resulted in two prominent cases: Nixon I and Nixon v. Administrator of General Services, 433 U.S. 425 (1977) (Nixon II). marked the first time that the Supreme Court recognized a “presumptive privilege” for presidential communications and established that the privilege is structurally rooted in the Constitution’s separation of powers.41Nixon I, 418 U.S. at 705–06, 708, 711.

The Court determined that the confidentiality of the president’s communications with his close advisors is protected under Article II,42Nixon II, 433 U.S. at 447. but that the privilege is qualified and not absolute.43Nixon I,418 U.S. at 705–06, 708. A balancing test is required when competing public values are implicated,44Nixon II, 433 U.S. at 447. and the privilege is limited to “communications ‘in performance of a President’s responsibilities . . . of his office.’”45Id. at 449. The privilege allows the president and important executive branch officials to withhold, under certain circumstances, sensitive material from Congress and the courts.46Nixon I, 418 U.S. at 708. The president can thus, for example, sometimes preserve the confidentiality of information and documents that pertain to executive-congressional relations if subject to a congressional investigation.

C. The Reagan Administration: Presidential Directives

President Ronald Reagan created a modern framework for expanded secrecy via two national security directives: Executive Order 12356 (“E.O. 12356”) and National Security Directive 84 (“NSD 84”). E.O. 12356 marked the first time in forty years that a president moved to restrict access to government information and to facilitate classification.47Mark J. Rozell, Executive Privilege in the Reagan Administration: Diluting a Constitutional Doctrine, 27 Presidential Stud. Q. 760, 762 (1997). The order tipped the scales balancing the public’s right to know and the government’s interest in secrecy in favor of the latter.48Id. It lowered the standard for classification to information designated as “confidential”49Exec. Order No. 12356, 47 Fed. Reg. 14,875, at § 1.1(a)(3) (Apr. 2, 1982) (allowing for “confidential” designation if an “unauthorized disclosure . . . reasonably could be expected to cause damage to the national security”). and eliminated the previous requirement that government demonstrate “identifiable damage”50Exec. Order No. 12065, 43 Fed. Reg. 28,949, at § 1-104. to security interests before classification.51Rozell, supra note 47. It also allowed agencies to classify or reclassify information after receiving a FOIA request.52Exec. Order No. 12356, § 1.6(d), 47 Fed. Reg. 14,874, 14,880 (Apr. 2, 1982).

Much like President Trump, President Reagan was particularly concerned about White House leaks. He responded by issuing restrictive policies for federal officials’ interactions with the press.53Rozell, supra note 47, at 763. The policies required, inter alia, that any contact with the press touching on classified information receive advance approval from a senior White House official, and that the employee submit a memorandum detailing all information disclosed.54Id. The policies also mandated that administration officials investigate leaks by “all legal methods.”55Id. These changes generated substantial negative media coverage, and in response the Reagan administration eliminated the controversial provisions from the policies.56Id.

President Reagan’s attempts to control access to information continued throughout his presidency. One year after implementing E.O. 12356, Reagan issued NSD 84 as something of an addendum.57Statement of Thomas Emerson to the Legislation and National Security Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations of the U.S. House of Representatives on the Constitutionality of the Presidential Directive on Safeguarding National Security Information on March 11, 1983, at 608. Downloaded as: “Review of the President’s National Security Decision Directive 84 and the Proposed Department of Defense Directive on Polygraph Use.” NSD 84 and its implementing nondisclosure agreements applied to every agency of the government that dealt with “classifiable” information, and to former and current government employees alike.58Id. at 618; see also Neil Roland, Reagan Agrees to Nine-Month Ban on Secrecy Pledge, UPI (Dec. 22, 1987), https://www.upi.com/Archives/1987/12/23/Reagan-agrees-to-nine-month-ban-on-secrecy-pledge/3070567234000/. NSD 84 mandated that all persons with authorized access to classified information be required to sign a nondisclosure agreement.59Id. The nondisclosure agreements restricted federal employees from disclosing any information that was “classified or [was] classifiable” to Congress or to the public.60Id. The term “classifiable” was not defined.61Peter Raven-Hansen & William C. Banks, Pulling the Purse Strings of the Commander in Chief, 80 Virginia L. Rev. 834, 924 n.464 (1994). Its vagueness substantially broadened the amount of restricted government information.62Stahl, supra note 18.

As with E.O. 12356, vociferous bipartisan criticism followed the implementation of NSD 84.63Id. Members of Congress argued that the directive violated government officials’ free speech rights and that the term “classifiable” was overly broad.64Id.; see also High Court to Review Congress’ Access, Daily News (Bowling Green, Ky.), Oct. 31, 1988, at 16, available at https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=KT01AAAAIBAJ&sjid=FkgEAAAAIBAJ&pg=4574%2C5784700. Critics contended that the term’s vagueness would chill the disclosure of executive information to the other branches.65Roland, supra note 58. Members of Congress argued that, by permitting information to be classified after the fact, NSD 84 amounted to a ham-handed effort to punish whistleblowers who disclosed information that embarrassed government officials.66Id. Senator Chuck Grassley stated that NSD 84’s practical effect was “not to maintain secrecy but to place a blanket of silence over federal workers.”

In response to the criticism, the Reagan administration narrowed the agreement’s scope to “unmarked classified information . . . in the process of a classification determination”67Stahl, supra note 18. and defined “classifiable” as applying to federal employees “who know, or reasonably should know” that the unclassified material is being reviewed for classification.68National Security Information Standard Forms, 52 FR 48367-01, 52 Fed.Reg. 48,367 (Dec. 21, 1987) (adding 32 C.F.R. § 2003.20(h)(1)32 C.F.R. § 2003.20(h)(1)). Congress in turn enacted legislation that blocked funding to implement President Reagan’s standard forms under NSD 84.69High Court to Review Congress’ Access, supra note 64, at 16. The legislation prohibited any standard form agreement that concerned information other than information specifically marked as classified, contained the term “classifiable,” or obstructed an individual’s ability to disclose information to Congress.70U.S. General Accounting Office, Information Security: Federal Agency Use of Nondisclosure Agreements 11 (1991).

The use of “classifiable” in the agreements and the responsive legislation were simultaneously challenged in court. A federal district court for the District of Columbia found the legislation unconstitutional due to its impermissible restriction on the president’s ability to execute the obligations imposed upon him “by his express constitutional powers and the role of the Executive in foreign relations.”71Nat’l Fed’n of Fed. Emps. v. United States, 688 F.Supp. 671, 685 (D.D.C. 1988). However, while the court ruled in favor of the Reagan administration with regard to the legislation, it acknowledged that the term “classifiable” was vague and that government officials’ First Amendment rights were “potentially impaired.”72Id. at 683; see also U.S. General Accounting Office, supra note 70 at 12. It therefore allowed the plaintiffs’ First Amendment challenges to the agreements to proceed. As the case wound its way through the appellate process, members of Congress put intense pressure on the Reagan administration to water down the agreements: Senator Chuck Grassley went so far as to urge federal employees to disregard the agreements they had signed.73Stahl, supra note 18. As a result, the administration dropped the “classifiable” language from NSD 84’s implementing nondisclosure agreements.74Id.

D. Standard Form 312

The modern manifestation of the Reagan administration secrecy agreements is Standard Form 312 (“SF 312”).75Id. It applies to government employees and contractors who have been granted security clearances for classified information.76Standard Form 312, Classified Information Nondisclosure Agreement, available at https://fas.org/sgp/othergov/sf312.pdf. It is indefinite in duration and prohibits the unauthorized disclosure of classified information in the interest of national security.77Id. Classified information is defined as “marked or unmarked classified information, including oral communications, that is classified under” any statute “that prohibits the unauthorized disclosure of information in the interest of national security; and unclassified information that meets the standards for classification and is in the process of a classification determination.”78Id.

Before President Trump took office, SF 312 was the government agreement most closely resembling a corporate NDA. Of course, there is a critical difference between these types of private and public agreements.

Corporate employers have broad legal latitude to restrict employees’ speech rights through mutual agreements between private parties. Government employers, on the other hand, are bound by constitutional constraints on state action, including the First Amendment.

Despite this difference, the proliferation of NDAs in the private sector is instructive in understanding why and how the White House is using them now.

E. Corporate NDAs

In the business context, NDAs are designed to protect a company’s business interest in shielding its proprietary information from competitors.79E. J. Dickson, What, Exactly, Is an NDA?, Rolling Stone (Mar. 19, 2019, 6:17 PM), https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/nda-non-disclosure-agreements-809856/ (citing attorneys and other legal experts describing the terms and uses for NDAs in the corporate context). In the early 20th century, employers in various industries began to use NDA clauses in employment contracts to protect their companies’ inner workings and reputations.80Id. These clauses constitute a legally binding contract that typically precludes employees from disclosing sensitive information—as defined by the employer.81Id. Usage first became widespread among Silicon Valley tech companies in the 1970s and has exploded in recent years to include a broad field of industries.82Lobel, supra note 23. Breach of an NDA subjects employees to termination and, in some cases, significant financial penalties.83Dickson, supra note 79.

The extensive use of private NDAs has drawn increasing reprobation in recent years, particularly in light of the #MeToo movement.84Id. One prominent example is the 2020 Democratic presidential primary debates, in which candidate Michael Bloomberg faced hostile questions and criticisms about NDAs that several female employees had signed as part of settlements for sexual harassment complaints against Bloomberg.85Lauren Egan, #MeToo Moment: Bloomberg on Debate Hot Seat for Comments about Women, NDAs, NBC News (Feb. 19, 2020, 10:25 PM), https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/politics-news/bloomberg-hot-seat-comments-about-women-non-disclosure-agreements-n1139411. Bloomberg’s company was sued multiple times over hostile work environment allegations, but the NDAs kept the content of the allegations and resulting settlements private.86Benjamin Swasey & Juana Summers, Bloomberg: 3 Women Who Made ‘Complaints About Comments’ Can Seek NDA Releases, NPR (Feb. 21, 2020, 4:35 PM),https://www.npr.org/2020/02/21/808280695/bloomberg-women-who-made-complaints-about-comments-can-now-seek-nda-releases. The Bloomberg example is unfortunately emblematic of a broader trend of secrecy agreements preventing women from speaking out about workplace sexual harassment; as a result, there is a nascent effort in the legal community to limit or ban the use of NDAs, at least for these purposes.87Dickson, supra note 79.

F. Corporatization of the Government

Tracking the long-term expansion of private NDAs, the federal government has increasingly “corporatized” over the last few decades. Intelligence agencies adopted the government-as-business metaphor as a guiding principle as far back as the 1940s, viewing policy makers as their customers.88Andrew L. Brooks, The Customer Metaphor and the Defense Intelligence Agency 2–3 (2016). In the 1960s, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara introduced the Planning, Programming and Budgeting System, a program designed by the Rand Corporation89Carol L. DeCandido, Evolution of Department of Defense Planning, Programming, and Budgeting System: From SECDEF McNamara to VCJCS Owens ii (1996), available at https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=447081. that structured defense agencies to analyze and respond to demands of its market consumers: the American people.90Samuel M. Greenhouse, The Planning-Programming-Budgeting System: Rationale, Language, and Idea-Relationships, 26 Pub. Admin. Rev. 271, 272 (1966). The 1990s saw further proliferation of businesslike approaches to government that were designed to implement corporate practices into public administration.91One prominent example is President Clinton’s doomed 1994 proposal to establish a public corporation to carry out the Federal Aviation Administration’s air traffic functions. See Bart Elias, Air Traffic Inc.: Considerations Regarding the Corporatization of Air Traffic Control, at 6, Cong. Research Serv. (May 16, 2017), available at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43844.pdf. Former Vice President Al Gore put it bluntly: “[A] lot of people don’t realize that the federal government has customers. We have customers. The American people.”92Albert Gore, From Red Tape to Results: Creating a Government that Works Better and Costs Less 43 (1993).

That sentiment still permeates the Executive Branch today. Jared Kushner, a senior adviser and the president’s son-in-law, set forth the Trump administration’s modus operandi as it assumed power in 2017: “The government should be run like a great American company. Our hope is that we can achieve successes and efficiencies for our customers, who are the citizens.”93Ashley Parker & Philip Rucker, Trump Taps Kushner to Lead a SWAT Team to Fix Government with Business Ideas, Wash. Post (Mar. 26, 2017, 10:00 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-taps-kushner-to-lead-a-swat-team-to-fix-government-with-business-ideas/2017/03/26/9714a8b6-1254-11e7-ada0-1489b735b3a3_story.html. Kushner’s statement came shortly after President Trump unveiled the new White House Office of American Innovation—consisting of former business executives with little-to-no political experience—with the mission of harvesting strategies and ideas from the business world and implementing those ideas into the government.94Id. It is hardly surprising, then, that one of the Trump White House’s first steps was to bring NDAs, a hallmark of private sector employment agreements, into federal government, particularly given President Trump’s longstanding affinity for the use of NDAs in his business and personal affairs.

G. President Trump’s Private Use

of NDAs

President Trump and the Trump Organization have utilized NDAs as standard practice for decades. President Trump has publicly confirmed his use of NDAs in business proceedings, boasting that his agreements were “so airtight” that “[he] never had a problem” with unauthorized disclosures.95Julie Pace & Chad Day, For Many Trump Employees, Keeping Quiet is Legally Required, AP News (June 21, 2016), https://apnews.com/14542a6687a3452d8c9918e2f0bf16e6 (describing Trump’s previous use of NDAs). He has routinely required employees and associates to sign NDAs prohibiting them from revealing information about the Trump Organization.96Id. These NDAs have typically included a non-disparagement clause, designed to prevent the employee from disclosing any disparaging secrets about Trump or his family.97Id. One such agreement prohibits employees indefinitely from disclosing information “of a private, proprietary or confidential nature or that Mr. Trump insists remain private or confidential.”98Id. Those bound by the agreement must return or destroy any confidential information in their possession upon Trump’s request.99Id.

President Trump has aggressively enforced his private NDAs through litigation. In 2013, his Miss Universe pageant sued a former contestant after she claimed the pageant was rigged.100Id. The organization won a $5 million judgment based on a non-disparagement provision in the contestant’s contract that prohibited any conduct that would bring “public disrepute, ridicule, contempt or scandal or might otherwise reflect unfavorably” on President Trump and associated businesses.101Id. In 1996, President Trump brought an unsuccessful suit against Barbara Corcoran, a New York businesswoman, who he claimed breached a confidentiality agreement.102Id.

President Trump has likewise liberally employed and enforced NDAs in his personal life. One prominent example is the lawsuit he brought in 1992 against his ex-wife, Ivana Trump, for allegedly breaching the nondisclosure portion of their divorce documents.103Id. He argued that her romance novel, For Love Alone, was based on the couple’s marriage and violated the divorce settlement NDA.104Id. The suit was settled out of court.105Id. In 2018, Stephanie Clifford publicly challenged the validity of an NDA (signed days before the 2016 election) intended to keep secret her alleged extramarital affair with President Trump.106Vanessa Romo, Stormy Daniels Files Suit, Claims NDA Invalid Because Trump Didn’t Sign At the XXX, NPR (Mar. 7, 2018, 10:17 AM), https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2018/03/07/591431710/stormy-daniels-files-suit-claims-nda-invalid-because-trump-didnt-sign-at-the-xxx. The agreement included a financial penalty of $1 million for each breach of its terms.107Id. Ultimately, the president agreed not to enforce the agreement following intense public scrutiny.108James Hill, Trump Won’t Enforce Stormy Daniels Nondisclosure Agreement, ABC News (Sept. 8, 2018, 6:40 PM), https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/trump-enforce-stormy-daniels-nondisclosure-agreement/story?id=57697574. In 2019, during an unplanned trip to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, President Trump required doctors and staff to sign NDAs before they could be involved in his treatment.109Carol E. Lee & Courtney Kube, Trump Asked Walter Reed Doctors to Sign Nondisclosure Agreements in 2019, NBC News (Oct. 8, 2020, 8:23 PM), https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/trump-asked-walter-reed-doctors-sign-non-disclosure-agreements-2019-n1242293.

And just this summer, the president attempted to enforce an NDA against his niece, Mary Trump, to prevent publication of a damaging family memoir.110Kranish, supra note 3. Mary Trump signed the agreement as part of a 2001 inheritance settlement, but the president was unable to prevent the book from being published.111Id. In an interview, Mary Trump accused the president of routinely using NDAs as swords to silence critics, leaning on “his power, his position and his money and his apparently endless supply of lawyers to run out the clock. Or just to outspend people who can’t afford it.”112Id. She described his NDAs as “a weapon to advance his own agenda.”113Id.

H. Trump Campaign and Transition Team NDAs

President Trump’s reliance on NDAs extended to his 2016 presidential campaign. His campaign team required the majority of staffers and associates to sign NDAs—including volunteers and even the distributor of his “Make America Great Again” hat.114Pace & Day, supra note 95. As noted above, use of NDAs has become relatively common in presidential campaigns.115See supra Section II.A. For example, former Senator Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign also required employees to sign NDAs.116Id.

Under the Trump Campaign NDA, employees are prohibited from disclosing any “confidential” information that is in “any way detrimental to the Company [referring here to the corporate campaign enterprise], Mr. Trump, any Family Member, any Trump Company or any Family Member Company.”117Trump Organization Nondisclosure Agreement 1–2, available at https://www.texastribune.org/2018/03/19/donald-trump-texas-campaign-non-disclosure-agreement/. The Campaign NDA also has a “[n]o [d]isparagement” clause requiring that signatories not “demean or disparage publicly the Company, Mr. Trump, any Family Member, any Trump Company or any Family Member Company.”118Id. Both clauses are indefinite, applying during the term of the service and “at all times thereafter.”119Id.

Mirroring President Trump’s business NDAs, the Campaign NDA defines “confidential information” as “all information (whether or not embodied in any media) of private, proprietary or confidential nature or that Mr. Trump insists remain private and confidential.”120Id. The provision lists examples of confidential information, including any information related to the personal life or finances of Trump, his family members, Trump companies, and family member companies.121Id. It also encompasses a broad range of communications—including meetings, conversations, notes “and other communications” of Trump and associates.122Id.

The president’s campaign relied on these NDAs in unsuccessfully pressuring former White House staffers Cliff Sims and Omarosa Manigault Newman not to publish tell-all books about their employment under Trump, ultimately taking Newman to arbitration.123Veronica Stracqualursi & Pamela Brown, Trump Claims He’s Suing ‘Various People’ For Violating Confidentiality Agreements, CNN (Aug. 31, 2019, 4:37 PM), https://www.cnn.com/2019/08/31/politics/madeleine-westerhout-trump-lawsuits/index.html. There, the campaign has suggested that Newman should pay nearly $1 million to cover the costs of an advertisement the campaign ran to respond to claims made in her book.124Maggie Haberman, Trump Campaign Suggests Omarosa Manigault Newman Pay for $1 Million in Ad Spending, N.Y. Times (Oct. 13, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/13/us/politics/trump-campaign-omarosa.html. Meanwhile, former campaign worker Jessica Denson is currently litigating a class action suit against the Trump campaign, seeking to have its NDAs voided on First Amendment grounds.125Kranish, supra note 3. The First Amendment issue presented by Denson’s lawsuit differs materially from that addressed here because, unlike the White House, the Trump Campaign is a private (or at least quasi-private) entity. In defending the lawsuit, the campaign’s legal team has characterized the agreement as a “standard business confidentiality agreement.” Id. She summarized her lawsuit to The Washington Post:“These NDAs are representative of the levers of fear that this campaign and administration wield over people. And if this lever of these NDAs is lifted, it is significant not only for the direct effect it has on people who have signed it, but for a general environment of people who are afraid to speak out.”126Id.

I. White House NDAs

President Trump’s White House NDAs differ immensely from the practices of previous administrations, bearing much more resemblance to a corporate agreement than a typical governmental restriction on classified information. Reporting characterizes the agreements as similar to those “typically given to reality show contestants.”127Cook & Restuccia, supra note 17; see also Kranish, supra note 3. Based on the Wolkoff NDA and reporting on agreements that other employees signed, we know that the general framework for the terms is as follows:

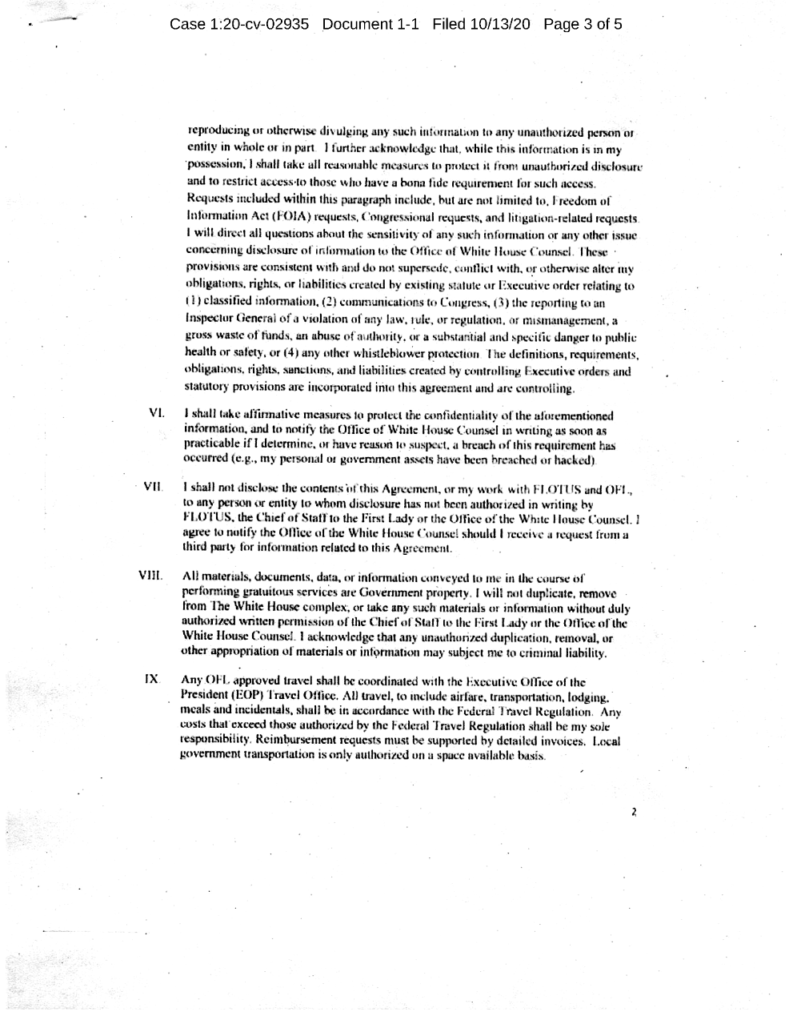

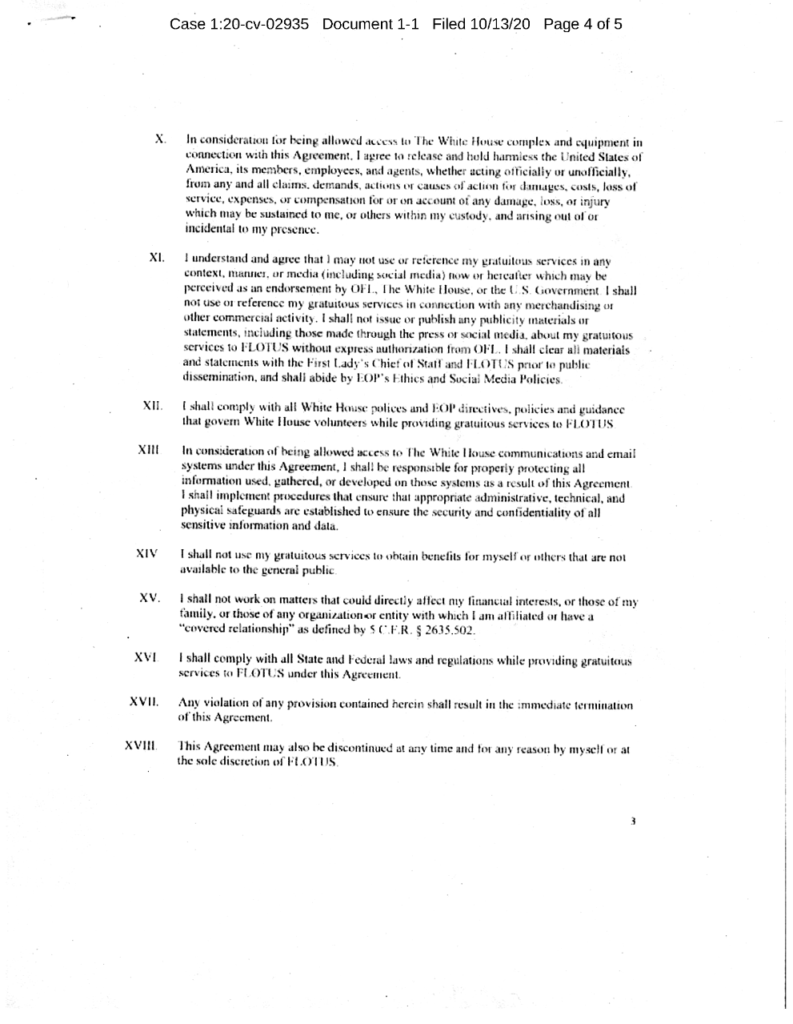

It applies indefinitely.128Wolkoff NDA at 2–3; Ruth Marcus, Trump Had Senior Staff Sign Nondisclosure Agreements, Wash. Post (Mar. 18, 2018, 3:56 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/trumps-nondisclosure-agreements-came-with-him-to-the-white-house/2018/03/18/226f4522-29ee-11e8-b79d-f3d931db7f68_story.html (citing sources who claimed to have seen and/or signed Trump White House NDA drafts). It bans employees from any unauthorized disclosure of “nonpublic, privileged and/or confidential information.”129Wolkoff NDA at 1. This includes information about the Trump family.130Id. The Wolkoff NDA restricts disclosure of “any and all information furnished” by the government, “information about which [signatory] may become aware during the course of performance,” and “the contents of [the NDA] and of [signatory’s] work with FLOTUS and OFL.”131Wolkoff NDA at 2–3. Unauthorized disclosures include “publishing, reproducing, or otherwise divulging” information “to any unauthorized person or entity in whole or in part.”132Id. These provisions reportedly mirror NDAs other staffers signed, prohibiting unauthorized disclosure of confidential work. An early draft prohibited individuals from revealing “confidential information” in any form, defined as “all nonpublic information [learned or accessed] in the course of . . . official duties in the service of the United States Government on White House staff.”133Marcus, supra note 128. It is unclear if this exact language was used in any final versions of the NDA, but it is consistent with the Wolkoff NDA’s scope. Some of the agreements reportedly reference the possibility of monetary damages of unspecified amount,134Cook & Restuccia, supra note 17. although Wolkoff’s does not.135Wolkoff NDA.

The early draft imposed a $10 million penalty, but this provision was not included in the version staffers signed.136Alison Frankel, Trump NDAs Can’t Silence ex-White House Officials: Legal Experts, Reuters (Mar. 19, 2018, 5:24 PM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-otc-nda/trump-ndas-cant-silence-ex-white-house-officials-legal-experts-idUSKBN1GV2UT. And unlike the Trump Campaign NDA, the White House NDA does not include a non-disparagement clause.137Wolkoff NDA.

As discussed in the following section, the White House NDA has profound constitutional implications for the dissemination of critical information about the inner workings of the executive branch. Speech about what happens in the White House will usually involve a matter of public concern. Suppressing information relevant to an administration’s competency or ethics information from the electorate harms the public interest. The last four years have served as a strenuous reminder of how much newsworthy conduct and conversation takes place behind closed doors in the West Wing. A blanket ban against sharing that information with the people—the polis charged with holding the president electorally accountable—is antithetical to the core values underlying the First Amendment.138In addition to constitutional challenges, the White House NDAs could be challenged on contractual grounds. Given the vagueness of their terms, it is unlikely that former employees were, at the time of signing, capable of knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily waiving their constitutional rights. Seegenerally Kathleen M. Sullivan, Unconstitutional Conditions, 102 Harv. L. Rev. 1415 (1989).

III. White House NDAs and First Amendment Rights

The First Amendment generally restrains the government’s ability to punish or limit speech. But its protections are circumscribed when the speech intrudes on certain governmental functions. These functions enjoy special solicitude because they drive our government’s operational purpose: enactment of the people’s democratic will. In other words, the executive branch requires some latitude in implementing the agenda on which the governing administration was elected.

To this end, the government must operate as an employer.139See generally Robert Post, Between Governance and Management: The History and Theory of the Public Forum, 34 UCLA L. Rev. 1713 (1987). And in that role, it must exercise some power to restrict speech based on a person’s status as a government employee.140See Heidi Kitrosser, The Special Value of Public Employee Speech, 2015 Sup. Ct. Rev. 301, 303 (2015). This means that the government “may impose restraints on the job-related speech of public employees that would be plainly unconstitutional if applied to the public at large.”141United States v. Nat’l Treasury Employees Union, 513 U.S. 454, 465 (1995). However, this power is not unbounded.142Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 563, 574 (1968).

Government employees, both current and former, retain First Amendment speech rights despite their employment by the government.143These employees also enjoy statutory whistleblower protections for disclosure of certain information in limited contexts (such as to Congress). These protections are acknowledged in the Wolkoff NDA. This paper addresses only the NDAs’ constitutional dimension. The press’s First Amendment rights are also implicated when government employees are prohibited from speaking.

In this section, we examine the government’s interests in regulating employee speech, the protections afforded to the press in receiving speech, and former and current government employees’ speech rights. After setting forth the relevant doctrinal frameworks, we apply them to the White House NDAs as enforced against hypothetical employee speakers.

We conclude that the NDAs are unconstitutional in a wide range of potential applications.

A. The Government’s Interests

The government’s right to restrict its employees’ speech derives from certain interests the government maintains as an employer. One such interest is in cultivating an efficacious work environment. For example, the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) exempts from disclosure the advice, recommendations, and opinions of government officials that are derived from deliberative, consultative, and decision-making processes of the government.1445 U.S.C. § 552(b)(5) (2016); see Dep’t of Interior v. Klamath Water Users Protective Ass’n, 532 U.S. 1, 8 (2001). The considerations underlying this exemption dovetail with those underlying executive privilege and other instances of government secrecy, such as the closure of Supreme Court conferences.145Benjamin S. DuVal, Jr., The Occasions of Secrecy, 47 U. Pitt. L. Rev. 579, 621 (1986). Protecting deliberative speech between presidents and their closest advisors allows for candid discussion of sensitive matters without concern that comments will later be publicized.146Nixon I, 418 U.S. at 705.

In addition to its interests as an employer, the government has an interest in national security, and it is this interest where the First Amendment offers employees the least protection: “[When] there is a reasonable danger that compulsion of the evidence will expose military matters which, in the interest of national security, should not be divulged . . . the occasion for the privilege is appropriate, and the court should not jeopardize the security which the privilege is meant to protect.”147U.S. v. Reynolds, 345 U.S. 1, 10 (1953); see also Aptheker v. Sec’y of State, 378 U.S. 500, 509 (1981) (“That Congress under the Constitution has power to safeguard our Nation’s security is obvious and unarguable.”). However, courts have struggled with the vagueness of the word “security.” In New York Times v. United States (hereinafter “the Pentagon Papers case”), Justices Black and Douglas stated that the term should not be used in order to “abrogate the fundamental law embodied in the First Amendment.”148403 U.S. 713, 719 (Black, J., concurring). Although courts and Congress often defer to the executive in matters of national security, that deference is not absolute, and government invocations of security interests are met with particular skepticism when fundamental rights—especially the rights of free political discussion and of the press—are implicated.149Id. at 719–20. The Court in the Pentagon Papers case not only recognized the competing values, interests, and rights at stake, but also illustrated that the presumption against prior restraints extends to cases in which the restricted speech relates to matters of national security.150Id.

B. Former Government Employees’ First Amendment Rights

Generally speaking, the First Amendment prevents the government from restricting expression because of its content.151Reed v. Town of Gilbert, 576 U.S. 155, 163 (2015). Thus, content-discriminatory laws are presumptively unconstitutional and must pass strict scrutiny—meaning the regulation must be narrowly tailored and further a compelling governmental interest.152See id. A law is content discriminatory on its face if it applies to particular speech because of the topic being discussed.153Id. Alternatively, a law can be content discriminatory if it cannot be justified without reference to the speech’s content. Id.

Former government officials receive the full protections of the First Amendment, but these protections may be curtailed as a consequence of government employment. One way the government has historically prevented disclosure of information by former employees is through prior restraints. Prior restraints—a preventive restriction on expression before it occurs—are considered “the most serious and the least tolerable infringement on First Amendment rights,”154Nebraska Press Ass’n v. Stuart, 427 U.S. 539, 559 (1976). and the government must rebut “a heavy presumption against” any prior restraint’s “constitutional validity.”155Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58, 70 (1963). “A long line of [Court decisions] makes it clear that [the government] cannot require all who wish to disseminate ideas to present them first to [government] authorities for their consideration and approval, with a discretion . . . to say some ideas may, while others may not, be disseminate[d].”156Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536, 557 (1965) (internal citations omitted). The government may nonetheless impose such a restraint if it fits “one of the narrowly defined exceptions” and if the government provides “procedural safeguards that reduce the danger of suppressing constitutionally protected speech.”157Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v. Conrad, 420 U.S. 546, 559 (1975).

Given that the government routinely imposes prior restraints on speech based on content through its classification system, one might wonder whether such a system is unconstitutional.158Indeed, the modern prepublication review regime is currently being challenged as unconstitutional under the First Amendment. See Notice of appeal, Edgar v. Ratcliffe, No. 20-1568 (4th Cir. 2020). The classification system first came under scrutiny in the landmark case Snepp v. United States, where the Supreme Court addressed the constitutionality of the CIA’s prepublication review requirement.159444 U.S. 507 (1980). Frank Snepp was a former CIA agent who had published a book, Decent Interval, which detailed CIA operations in Vietnam. Snepp failed to submit his manuscript for prepublication review and approval to the CIA, as contractually required. The Court found the prepublication review requirement to be a reasonable means to protect classified information, denying Snepp’s argument that the prior restraint was unconstitutional. Crucially, the Court’s ruling in Snepp did not extend to unclassified information.160McGehee v. Casey, 718 F.2d 1137, 1141 (D.C. Cir. 1983).

The Court did not squarely address the constitutionality of the classification system itself in Snepp, but the D.C. Circuit did so a few years later in McGehee v. Casey.161Id. at 1139. As in Snepp, the employee in McGehee signed an agreement with the CIA that barred him from revealing classified information without prior approval.162Id. at 1141. However, unlike in Snepp, the employee in McGehee did submit his manuscript to the CIA for prepublication approval, portions of which the CIA censored.163Id. The court applied a two-part test which heavily resembled strict scrutiny.164See id. at 1142–43. Oddly, the court did not label the test strict scrutiny. First, the court determined whether the restriction protected a “substantial government interest unrelated to the suppression of free speech.”165Id. at 1142 (internal quotation marks omitted). Then, the court examined whether the restriction was “narrowly drawn to ‘restrict speech no more than is necessary to protect the substantial government interest.’”166Id. at 1143. Applying these principles, it determined that the government had a compelling interest in protecting information important to national security.167Id. The court also found that the regulation was narrowly drawn—since the classification system was not overly vague and required a reasonable probability of harm—and thus concluded that the classification system did not violate the First Amendment.168Id. Importantly, the court noted that there was no government interest in censoring unclassified material, and therefore the government could not censor it.169Id. at 1141.

When classified material is not at issue, the First Amendment generally proscribes governmental discrimination of speech based on content or viewpoint.

While viewpoint discrimination is often seen as a subset of content discrimination—“the distinction [between the two] is not a precise one”170Rosenberger v. Rector & Visitors of Univ. of Va., 515 U.S. 819, 831 (1995).—it is considered an especially egregious species.171Id. at 829. In cases addressing viewpoint discrimination, the Court has expressed an extremely low tolerance for the government imposing any particular point of view.172See Matal v. Tam, 137 S. Ct. 1744, 1763 (2017) (“[P]ublic expression of ideas may not be prohibited merely because the ideas are themselves offensive to some of their hearers.”) (quoting Street v. New York, 394 U.S. 576, 592 (1969)).

C. White House NDAs as Applied to Former Government Employees

A former government official challenging the White House NDAs’ constitutionality would have a strong case. The NDAs are prior restraints that do not sufficiently cabin governmental discretion. They are also content-based and therefore must survive strict scrutiny.

The White House NDAs are ex ante restrictions on the communication of non-classified information obtained through governmental employment. In other words, the NDAs prohibit discussing certain non-classified information about the Trump White House obtained through employment, and thus restrict speech based on its content. And because they require governmental permission for such discussions, they are prior restraints on speech. But unlike the restrictions at issue in McGehee, the White House NDAs extend well beyond classified information.

The White House NDAs do not provide adequate standards or procedural safeguards to justify their prior restraint on speech. The Wolkoff NDA requires signatories to “direct all questions about the sensitivity of any such information or any other issue concerning disclosure of information to the Office of White House Legal Counsel.”173Wolkoff NDA at 2. It likewise bars disclosures about the NDA or Wolkoff’s work with the First Lady that “have not been authorized in writing by FLOTUS, the Chief of Staff to the First Lady or the Office of the White House Counsel.”174Id. This language includes no standards that might cabin governental discretion. White House Counsel could thus refuse to authorize disclosure of a host of information falling into broad categories—such as nonpublic information—which the government has no legitimate interest in suppressing.175See Cox, 379 U.S. at 557 (collecting cases where prior restraints were invalidated for failure to limit governmental discretion). Nor does the White House NDA require White House Counsel to make an authorization determination within any specific time frame, or provide for any mechanism to challenge a denial of authorization.176See Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U.S. 51, 58–60 (1965) (setting forth procedural requirements for prior restraints); United States v. Marchetti, 466 F.2d 1309, 1317 (4th Cir. 1972) (requiring that speech subject to authorization be reviewed within thirty days). Snepp and McGehee provide the government no shelter, given that the White House NDAs target unclassified information.177See supra text accompanying notes 161–70.

There are further constitutional defects. The Wolkoff NDA bans unauthorized disclosure of all “information about the First Family,” about Wolkoff’s “work with FLOTUS,” and about the contents of the NDA itself.178Wolkoff NDA at 1–2. And Newman, the former campaign and White House staffer now in arbitration against the Trump campaign, reportedly refused to sign a White House NDA which would have prohibited her from disclosing information about a broad variety of categories, including the “assets, investments, revenue, expenses, taxes, financial statements, actual or prospective business ventures, contracts, alliances, affiliations, relationships, affiliated entities, bids, letters of intent, term sheets, decisions, strategies, techniques, methods, projections, forecasts, customers, clients, contacts, customer lists, contact lists, schedules, appointments, meetings, conversations, notes and other communications” of “Trump, Pence, any Trump or Pence Family member, any Trump or Pence company, or any Trump or Pence Family Member Company.”179Dawsey & Parker, supra note 10. The language in the Wolkoff and Newman180Assuming that reporting on the NDA Newman allegedly refused to sign is accurate. NDAs baldly forecloses multiple topics of discussion, thus discriminating based on content.

Determining that the White House NDAs are content-based does not end the inquiry. Content discriminatory restrictions can be upheld if they pass strict scrutiny. This means that the White House NDAs must serve a compelling governmental interest, a potentially insurmountable hurdle for the government given the McGehee court’s assessment that there is no governmental interest in protecting unclassified information. However, this analysis would depend on the specific situation at issue, as the governmental interest will change depending on the circumstances of any particular NDA enforcement scenario. A separate and even more daunting obstacle for the government is the requirement of narrow tailoring, a difficult argument for the government given the NDAs’ remarkably broad terms.

Consider the following hypothetical: a White House aide who signed an NDA sits in on a conversation between Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. Pompeo informs Trump that killing Iranian Major General Qassim Soleimani would be “disastrous” for Middle Eastern policy.181This fictitious hypothetical is loosely drawn from Soleimani’s assassination earlier this year. See The Killing of Gen. Qassim Suleimani: What We Know Since the U.S. Airstrike, N.Y. Times (Jan. 4, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/03/world/middleeast/iranian-general-qassem-soleimani-killed.html. The next day, Trump orders an air strike which kills Soleimani. Shortly after, the aide leaves the administration and wants to reveal to a newspaper what she heard. The White House gets word that the former aide has contacted a journalist and threatens to enforce the NDA if the former aide discloses Pompeo’s statement. Would the NDA violate the First Amendment if enforced in this way?

If the NDAs were narrowly tailored—which they are not, based on what we know182See infra text accompanying notes 200–04.—one might argue that the NDA could pass strict scrutiny as applied here. The argument would hinge on the premise that keeping deliberations of this type private furthers a compelling government interest because it allows officials to speak their minds without fear of the public scrutinizing every idea.183See Rozell, supra note 26, at 1122. This line of argument borrows from the executive privilege that presidents invoke to shield information from other branches of government.184See supra Section II.A. Here, if every opinion Pompeo expresses to Trump could potentially become public, Pompeo may be more reserved with his advice in order to avoid the perception of discord within the White House.185See id. at 1070. There is perhaps a colorable argument to be made that a narrowly tailored NDA might survive strict scrutiny in this scenario, given that the Secretary of State is one of the president’s closest advisors.

DOJ invokes this same deliberative interest in enforcing Wolkoff’s NDA.186See Complaint, United States v. Wolkoff, No. 20-2935 (D.D.C. filed Oct. 13, 2020). It cites multiple portions of Wolkoff’s book.187See id. at 12. In one, she describes “her view (based on inferences that she derived from information received during the course of her confidential position) that, had the First Lady been present at the White House during a particular period in time leading up the issuance of the [Travel Ban], the President might not have signed Executive Order 13769 [implementing the Travel Ban].”188Id. Executive Order 13769 suspended entry into the United States of individuals from seven predominately Muslim countries: Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. A later iteration of the ban was upheld by the Supreme Court in Trump v. Hawaii, 138 S. Ct. 2392 (2018). In another portion, she recounts a discussion with the First Lady about “the President’s decision to eliminate a ban on the importation of big game trophies” and how the First Lady “convinced the President to put that decision on hold.”189Id. DOJ contends that publicizing these accounts will “undermine the expectation of future Presidents and First Ladies that their confidential deliberations will be protected and preserved from the public glare.”190Id. This justifies enforcement of the NDA, DOJ concludes, because the “President’s policy conversations are self-evidently core matters on which the President is entitled to receive confidential advice without fear that such internal deliberations will be leaked to the press.”191Id.

DOJ’s argument seems quite weak, highlighting the limitations of the deliberative process interest.192It is not even clear whether the deliberative process interest applies (or if it does, to what extent) to discussions between the President and First Lady, as opposed to between the President and senior policy advisors. See Schmidt, supra note 2 (quoting Professor Heidi Kitrosser). The passage in Wolkoff’s book about the Travel Ban includes no advice given by the First Lady at all—it instead sets forth Wolkoff’s opinion on how the president might have potentially made a different policy decision had he been privy to the First Lady’s advice. This is well beyond the bounds of any governmental interest in protecting important deliberations. While the First Lady’s input regarding the trophy hunting ban could be construed as policy advice, the government’s only interest in protecting it is based “solely on the broad, undifferentiated claim of public interest in the confidentiality of such conversations.”193See Nixon I, 418 U.S. at 706. Because this is a far cry from an interest in protecting “military, diplomatic, or sensitive national security secrets,” the deliberative interest is diminished and must be weighed against competing values.194See id. And there is a significant countervailing public interest at stake: informing the electorate that the president’s policy decision on trophy hunting hinged on the determinative advice of the First Lady—someone with no expertise in issues related to animal conservation. Allowing these types of deliberative concerns—unrelated to highly sensitive national security matters—to prevent the release of valuable information to the public would mark a troubling elevation of executive privilege-type interests.195See Heidi Kitrosser, Stephanie Wolkoff’s Revelations Are Exactly What the First Amendment Should Protect, Atlantic (Oct. 15, 2020 6:15 AM), https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/10/first-amendment-disgrace/616745/.

Consider another hypothetical. A White House aide who has signed an NDA is sitting in on an Oval Office meeting in the wake of the September 2020 New York Times report disclosing details of the president’s federal tax returns.196In September 2020, the New York Times reported that President Trump’s tax returns show that he has paid no income tax in ten of the previous fifteen years. See Russ Buettner, Susanne Craig & Mike McIntire, Long-Concealed Records Show Trump’s Chronic Losses and Years of Tax Avoidance, N.Y. Times (Sept. 27, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/09/27/us/donald-trump-taxes.html. In the course of the meeting, Trump chuckles and says, “Isn’t it a beautiful thing that I’ve paid virtually no federal income tax in fifteen years? I’ll just call this reporting fake news and it won’t have any effect on my re-election.” The aide leaves the administration shortly after and now wants to relay the story to the Times to help confirm their reporting. Could the NDA be applied to prevent the former aide from disclosing Trump’s comment?

The answer would likely be no as the application would not pass strict scrutiny. There is no plausible governmental interest in hiding Trump’s embarrassing or damaging personal statements. One of the First Amendment’s goals is to prevent governmental suppression of embarrassing information.197See Pentagon Papers, 403 U.S. at 723–24 (1971) (Douglas, J., concurring).

Thus, the government has no substantial interest in preventing information becoming public that may embarrass the president—the compelling government interest must have an interest unrelated to suppressing speech.

Instead, such information contributes to the “uninhibited, robust, and wide-open” public debate that the First Amendment is designed to encourage.198See id. at 724 (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 269–70 (1964)). One might attempt to argue that public revelation that the president is in serious debt constitutes some sort of national security interest, but this claim is weak given that the Times has already published extensive details on the president’s debts drawn from his tax returns. And if anything, a president’s significant debt is itself a national security concern of which the public should be aware. Any interest the government might claim beyond mere avoidance of embarrassment would be vastly overshadowed by the public’s interest ahead of an election in vital information about the president’s financial obligations.

Regardless of the governmental interest at stake, the NDAs are not narrowly tailored and are thus unconstitutional. As noted above, they apply to all “nonpublic” information. The Wolkoff NDA also bars unauthorized disclosure of all information about the First Family, “any and all information furnished” by the government, and all “information about which [signatory] may become aware during the course of performance.”199Wolkoff NDA at 1. This startlingly broad language is consistent with that of the reported Newman NDA (and other past Trump agreements), which restricted information about Trump’s family, the Pence family, or Trump’s businesses.200Dawsey & Parker, supra note 10.

These provisions would be overbroad under any circumstance, since they extend well beyond what is needed to protect legitimate governmental interests.201These overbreadth concerns would render the NDAs constitutionally suspect even if they were not content discriminatory. See United States v. Stevens, 559 U.S. 460, 473 (2010) (holding that, in the First Amendment context, a speech restriction “may be invalidated as overbroad if a substantial number of its applications are unconstitutional, judged in relation to the [restriction’s] plainly legitimate sweep.” (internal quotation marks omitted). Indeed, it is difficult to conceive of a provision more emblematic of textbook overbreadth than one restricting all “information about which” an employee “may become aware during the course of performance.” And the lack of legitimate governmental interest is particularly apparent in the ban on sharing of any information whatsoever about the First Family.

The only purpose these provisions might serve would be to protect the president’s image, which there is no legitimate governmental interest in protecting.

Perhaps even more troubling is the agreements’ infinite duration. This indefinite application202Wolkoff NDA at 1–2; see also Dawsey & Parker, supra note 10. surely exceeds the timeframe necessary to protect legitimate governmental interests. Recall the earlier hypothetical involving Secretary Pompeo. While protection of the deliberative process could (at least in theory) be deemed necessary in rare circumstances to ensure that the president receives uninhibited advice, the burden on the aide’s speech need not last indefinitely to achieve that goal. Pompeo would not plausibly be discouraged from giving the president advice because of a risk that his statements will be disclosed twenty years from now. An indefinite prohibition restricts far more speech than necessary.203A court could, however, blue-pencil the NDA such that it only applies for a reasonable period. A court may alter a contractual provision if the contract “is susceptible of division and apportionment.” 17A Am. Jur. 2d Contracts § 394 (2020).

Because of their overbroad scope and indefinite duration, the NDAs are not narrowly tailored and should fail strict scrutiny.

Turning now to viewpoint considerations, based on the Wolkoff NDA and other reported language, the NDAs are likely viewpoint neutral. On their face, the NDAs only prohibit speech based on the speech’s content. While Trump’s Campaign NDAs contained a clause preventing disparagement—which would be blatant viewpoint discrimination—all sources indicate that this clause is not included in any White House NDAs.204Frankel, supra note 136. Instead, unauthorized disclosure of content the NDAs restrict would be a violation, regardless of whether the breach painted Trump in a positive or negative light. The NDAs are therefore facially viewpoint neutral. But Trump’s enforcement of the NDAs might still constitute viewpoint discrimination.

Facially neutral laws may violate the Constitution if they are applied in a discriminatory manner.205See Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 373–74 (1886). For example, prosecutors are not allowed to prosecute individuals based upon arbitrary classifications, such as race or religion, using facially neutral laws.206Wayte v. United States, 470 U.S. 598, 608 (1985) (quoting Bordenkircher v. Hayes, 434 U.S. 357, 364 (1978)). One such arbitrary classification includes exercising one’s First Amendment rights.207See id. As a result, the government cannot criminally prosecute an individual based on that individual’s viewpoint. This claim is known as selective prosecution and the remedy is for the court to dismiss the criminal charges.208Stephen E. Arthur & Robert S. Hunter, 1 Federal Trial Handbook: Criminal § 12:30 (4th ed. 2019). In a similar vein, a government official can be sued under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for bringing a civil lawsuit or counterclaim against an individual in retaliation for that individual’s protected speech.209See DeMartini v. Town of Gulf Stream, 942 F.3d 1277, 1300 (11th Cir. 2019); see also Greenwich Citizens Comm., Inc. v. Ctys. Of Warren & Wash. Indus. Dev. Agency, 77 F.3d 26, 30–31 (2d Cir. 1996);Harrison v. Springdale Water & Sewer Comm’n, 780 F.2d 1422, 1427–28 (8th Cir. 1986); Bell v. Sch. Bd. of Norfolk, 734 F.2d 155, 158 (4th Cir. 1984) (Rosenn, J., concurring).

Just as the Constitution forbids selective enforcement of facially neutral criminal laws, it does not allow Trump to enforce his NDAs in a viewpoint-discriminatory manner.

While we have located no case where a defendant has invoked this defense against a civil lawsuit, the argument logically follows as a synthesis of the above case law. If the government cannot criminally prosecute an individual because of that individual’s viewpoint, and the government can be sued under § 1983 if it brings a civil suit against an individual in retaliation for that individual’s viewpoint, it naturally follows that a court should prevent Trump from enforcing an NDA based on an individual’s viewpoint.

Recall the earlier hypothetical where the Trump aide reveals to the New York Times Trump’s confirmatory statement that he has paid hardly any federal income tax in fifteen years. Imagine that the day following the story about that statement, a different aide who also signed an NDA goes on a nightly cable news program. She says that she saw copies of Trump’s tax returns on the Resolute desk and, upon inspecting them, concluded that the Times’reporting does not accurately reflect his tax returns’ contents. In both situations, the aides breached the NDA. Now imagine DOJ subsequently sues the first aide for revealing Trump’s statement about not paying his taxes. Since that aide can point to a similarly situated individual who also breached the agreement (but to Trump’s benefit) and who was not sued, the aide can claim that the administration is enforcing the NDAs in a viewpoint-discriminatory manner and should succeed in having the lawsuit dismissed.210Cf. United States v. Armstrong, 517 U.S. 456, 465 (1996) (allowing dismissal of criminal charges if defendant shows similarly situated individuals of a different race that were not prosecuted). While selective prosecution claims can practically be difficult to prove, see generally Michael G. Mills, Note, The Death of Retaliatory Arrest Claims: The Supreme Court’s Attempt to Kill Retaliatory Arrest Claims in Nieves v. Bartlett, 105 Cornell L. Rev. 2059, 2091 n.199 (2020) (collecting sources criticizing how difficult it is to prove a selective prosecution claim), it still provides a theoretical framework in the civil context for future litigators to fight selective enforcements of government NDAs.

More direct evidence would also suffice. For example, if Trump tweeted in response to the first aide’s statement to the Times, “This is what low energy backstabbers get when they betray me! I’ll sue this SAD aide for everything she’s worth!” the aide should also be able to dismiss the lawsuit. In these scenarios, the facially neutral NDA is being applied in a viewpoint-discriminatory manner.

D. The Press’s First Amendment Rights

The First Amendment rights of the press are twofold: the right to receive speech and the right to gather news.211See Va. State Bd. of Pharmacy v. Va. Citizens Consumer Council, Inc., 425 U.S. 748, 756–57 (1976); Branzburg v. Hayes, 408 U.S. 665, 681 (1972); CBS Inc. v. Young, 522 F.2d 234, 238 (6th Cir. 1975).

Because the right to receive speech is understood as an extension of a protected speaker’s right to speak, the press must establish the presence of a willing speaker in order to seek coverage by the First Amendment.212Price v. Saugerties Cent. Sch. Dist., 305 Fed. App’x 715, 716 (2d Cir. 2009); see also Pa. Family Inst. Inc. v. Black, 489 F. 3d 156, 166 (3d Cir. 2007). Meanwhile, the right to gather news, albeit subordinate to the duty to obey generally applicable laws, protects news agencies from government restrictions that target newsgathering activities.213Branzburg, 408 U.S. at 707–08.

As a corollary to the right of free speech, the Supreme Court clearly recognizes the listener’s right to challenge an abridgement of speech.214See Va. State Bd. of Pharmacy, 425 U.S. at 756–57. Such a challenge presupposes a willing speaker. In fact, “the success of a third-party recipient’s First Amendment claim is entirely derivative of the First Amendment right of the [willing] speaker subject to the challenged regulation.”215Price, 305 Fed. App’x at 716. Showing a willing speaker’s existence is therefore essential for standing.216Pa. Family Inst., 489 F. 3d at 166. Once the listener shows a willing speaker, the listener’s claim becomes entirely derivative of the speaker’s claim.217Price, 305 F. App’x at 716.

To show a willing speaker’s existence, “a party must show at least that but for a challenged regulation of speech, a person would have spoken.”218Pa. Family Inst., 489 F. 3d at 166; see ACLU v. Holder, 673 F.3d 245, 255 (4th Cir. 2011); Fox v. Leavitt, 572 F. Supp.2d 135, 141 (D.D.C. 2008) (“To maintain a ‘right to listen’ claim, a plaintiff must clearly establish the existence of an otherwise willing speaker, and that the challenged policies caused the speaker to be unwilling to speak.”). Some courts refuse to find a willing speaker where the restrained person waived the speech restriction.219Town of Verona (Oneida County) v. Cuomo, 2013 WL 5839839, at *5 (N.D.N.Y. Oct 30, 2013); see Democratic Nat. Committee v. Republican Nat. Committee, 673 F.3d 192, 206 (3d Cir. 2012) (“A court can enforce an agreement preventing disclosure of specific information without violating the restricted party’s First Amendment rights if the party received consideration in exchange for the restriction.”). For example, if a person has bound themselves to refrain from some speech as part of a settlement agreement, that person is not a willing speaker for a right-to-receive-speech claim.220Town of Verona, 2013 WL 5839839, at *5. However, just because a speaker has waived their right to speak does not mean a court can presume that the speaker is not willing.221Stephens v. County of Albemarle, 2005 WL 3533428, at *7 (W.D. Va. Dec. 22, 2005). For example, if the waiver was an unconstitutional condition, courts will not presume the speaker is not willing.

E. White House NDAs as Applied to the Press

To assert a claim that the NDAs violate the press’s right to receive speech, the press would need to find a willing speaker—either a former or current government official who signed a White House NDA—and document that speaker’s willingness to provide unclassified information about the president. Assuming a press plaintiff could satisfy that burden, it could demonstrate that the Trump NDAs would infringe upon its right to receive speech and gather news. Upon demonstrating a willing speaker, the press’s claim becomes wholly derivative of the willing official’s claim.

Consider again a former White House employee who wishes to speak to the press. By unconstitutionally infringing on the former employee’s First Amendment speech in a content discriminatory manner,222Seesupra Section II.G. the NDAs also infringe on the press’s right to receive speech and gather news. The NDAs would prevent the press from receiving, among other things, information related to President Trump’s relationships, decisions, conversations, and notes, as well as information related to the president’s family and any affiliated business organizations.223Id. In such an instance, courts would not presume that the former employee waived First Amendment rights by signing the NDA because the NDA would constitute an unconstitutional condition for the reasons set forth above.

To place this example in more tangible terms, recall the earlier hypothetical about the aide who wants to disclose to the New York Times that Trump confirmed that he has paid virtually no federal income tax in fifteen years. Change the facts a little so that a Times reporter instead approaches the aide once she leaves the Trump administration and asks her whether Trump made any comments in her presence about his tax returns. The aide responds, “He did, and I would tell you all about it but I’m prohibited by this NDA.” The aide does not want to bring a lawsuit challenging the NDAs’ validity herself. Since the press has established a willing speaker, it may sue to invalidate the NDA on the grounds that it violates its right to receive speech. Since the NDA violates the aide’s First Amendment rights,224Id. the press may successfully assert its derivative claim to invalidate the NDA.

F. Current Governmental Employees’ First Amendment Rights

Compared to former government employees, current employees enjoy narrower First Amendment protections. For example, the government may impose some restrictions on current employees’ speech on the basis of content.225See infra.

But the Supreme Court “has made clear that public employees do not surrender all their First Amendment rights by reason of their employment. Rather, the First Amendment protects a public employee’s right, in certain circumstances, to speak as a citizen addressing matters of public concern.”226Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410, 417 (2006).