By Kyle McKenney

November 15, 2023

Introduction

For the first time in 20 years, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) has revised its principal guidance on regulatory review.1Office of Mgmt. & Budget, Circular A-4: Regulatory Analysis, Draft for Public Review (2023) [hereinafter Circular A-4 (2023)]. OIRA, an office within the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB), is responsible for reviewing all major regulations in the U.S. Since 2003, agencies and OIRA have relied on the guidance in Circular A-4 when assessing regulations.2Office of Mgmt. & Budget, Circular A-4: Regulatory Analysis 14 (2003) [hereinafter Circular A-4 (2003)]. Across vastly different presidential administrations, 15 different administrators of OIRA, and shifting political landscapes, Circular A-4 has stood firm. While OIRA has offered supplemental guidance on topics such as environmental justice,3Exec. Order 12,898, 59 Fed. Reg. 31 (Feb. 16, 1994) (directing federal agencies to identify and address the disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of regulatory actions on minority and low-income populations). it has never updated Circular A-4 — until now. In April 2023, OIRA, under new Administrator Richard L. Revesz, circulated a revised draft of Circular A-4.4Request for Comments on Proposed OMB Circular No. A–4, ‘‘Regulatory Analysis,” 88 Fed. Reg. 20915, (April 7, 2023). Henceforth, the two versions of Circular A-4 will be distinguished. as Circular A-4 (2003) and Circular A-4 (2023). Given the centrality of Circular A-4 to regulatory policy and its staying power, it is crucial this revision make lasting improvements.

The primary mechanism for regulatory review under Circular A-4 is cost-benefit analysis (CBA).5Circular A-4 (2003) at 10. CBA is an analytical tool wherein costs and benefits of potential regulatory options are expressed in a common measure, dollars, and weighed against one another to determine which produces the highest net benefits.6Id. However, the size of total benefits is not the only important factor; who receives the benefits and burdens of regulation matters as well. To understand the impact of regulations, agencies can use distributional analysis to examine how the magnitude and nature of effects vary across demographic lines, including income, race, sex, gender, disability, occupation, geography, and so on.7Circular A-4 (2023) at 61.

Regulatory guidance has recommended the consideration of such distributional effects since the Clinton Administration.8Exec. Order No. 12,866, §§ 1(a), (b)(5), 58 Fed. Reg. 190 (Sept. 30, 1993). However, agencies consistently disregard distributional analysis and OIRA has never made a serious effort to require it.9See Richard L. Revesz, Regulation and Distribution, 93 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1489, 1491 (2018). This led current OIRA Administrator Richard Revesz to argue, shortly before his appointment, that “efforts to make distributional analysis a meaningful component of the evaluation of regulation, or, for that matter, even a non-trivial component, cannot be regarded as anything other than a failure.”10Richard L. Revesz & Samantha P. Yi, Distributional Consequences and Regulatory Analysis, 52 Envtl. Rev. 53, 55 (2022). This is in spite of decades of research showing certain communities suffer greatly disproportionate harms from hazards such as pollution and receive disproportionately fewer benefits from regulations.11See H. Spencer Banzhaf et al., Environmental Justice: Establishing Causal Relationships, 11 Ann. Rev. Res. Econ. 377, 379 (2019); see Jack Lienke et al., Making Regulations Fair: How Cost-Benefit Analysis Can Promote Equity and Advance Environmental Justice, Inst. for Pol’y Integrity 4 (2021). The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) noted over 30 years ago that “[r]acial minority and low-income populations experience higher than average exposures to pollutants, hazardous waste facilities, contaminated fish and agricultural pesticides in the workplace.” Env’t Prot. Agency (hereinafter, EPA), Environmental Equity: Reducing Risk for All Communities 3 (June 1992). The new Circular A-4 (2023) may overhaul how agencies consider and analyze distributional effects. One of the primary mechanisms it seeks to expand and systematize distributional analysis is income weighting.12Circular A-4 (2023) at 65-66.

At a basic level, an additional dollar of benefit or burden to a poor person is worth more than the same benefit or burden to a wealthy person. Income weighting is a function to incorporate that principle into regulatory analysis by varying the value of benefits or costs based on the income of those benefitted or burdened.13Marc Fleurbaey & Rossi Abi-Rafeh, The Use of Distributional Weights in Benefit-Cost Analysis: Insights from Welfare Economics, 10 Rev. Envtl. Econ. & Pol’y 286, 286 (2016). OIRA’s endorsement of income weighting in Circular A-4 (2023) is perhaps the most significant change in the treatment of distributional analysis. By incorporating income weighting into their CBAs, agencies will be able to examine the distributional effects of regulations based on income, enabling relatively simple and interoperable comparisons of regulatory options.

This article begins with an overview of distributional analysis. It then examines the changes made in Circular A-4 (2023), particularly with respect to income weighting. It also provides background on income weighting, examines potential legal and practical constraints on the use of income weighting, and explores certain critiques of income weighting. I conclude that income weighting, if it can overcome the constraints, should lead to more rational and equitable regulation.

I. Background on Distributional Analysis

Distributional analysis, which examines how effects of regulatory options vary across demographic categories, is crucial to ensure regulations do not perpetuate inequities for disadvantaged or marginalized groups through consistent, disproportionate allocation of costs and benefits in otherwise net beneficial regulations.14Exec. Order No. 13,985 § 1, 86 Fed. Reg. 7009 (Jan. 20, 2021). A robust distributional analysis should enable agencies to prevent such disproportionate allocations and go a step further by answering the question of “when are the better distributional consequences of one alternative sufficient to overcome another alternative’s higher net benefits?”15Revesz, supra note 10 at 53. Agencies have been explicitly directed to consider distributional effects of regulations since the Clinton administration’s Executive Order 12,866.16Exec. Order No. 12,866 §§ 1(a), (b)(5).5, 58 Fed. Reg. 190 (Sept. 30, 1993). The Obama administration updated regulatory guidance with Executive Order 13,563, but its guidance on distributional consequences of regulations was substantively the same as Executive Order 12,866.17Compare Exec. Order No. 13,563 §§ 1(b)-(c), 76 Fed. Reg. 3831 (Jan. 21, 2011) with Exec. Order No. 12,866 §§ 1(a), (b)(5).5, 58 Fed. Reg. 190 (Sept. 30, 1993). OIRA is charged with ensuring compliance with these executive orders,18Exec. Order No. 12,866 § 2(b), 58 Fed. Reg. 190 (Sept. 30, 1993); Exec. Order No. 13,563 § 6(b), 76 Fed. Reg. 3831 (Jan. 21, 2011). but has made little to no effort to force or even encourage agencies to measure or analyze distributional effects.19Revesz, supra note 10. As it now stands, agencies rarely engage in distributional analysis, and, even when they do, it is cursory, rarely quantitative, and often serves to simply affirm predetermined regulatory decisions.

A study of 24 major Obama-era regulations found none engaged in comprehensive quantitative distributional analysis.20Lisa A. Robinson et al., Attention to Distribution in U.S. Regulatory Analyses, 10 Rev. Env’t Econ. & Pol’y 308, 314-16 (2016). This study analyzed “major environmental, health, and safety regulations” reviewed by the OMB in fiscal years 2010–2013 “for which a reasonably complete [CBA] was developed.”21Id. at 311. With just three exceptions, the regulations only provided national-level estimates of health-related benefits.22Id. at 313. Of those regulations that addressed distribution of benefits among population subgroups, none “report[ed] the monetary value of the benefits” or “indicate[ed] how the costs are distributed across population subgroups.”23Id. at 314. Instead, the regulation simply made conclusory statements that it was “not expected to adversely affect the health of minorities, low-income groups, or children.”24Id. at 313. This isn’t distributional analysis — there is no computation of how benefits and burdens are distributed across various demographics, merely a bare assertion that a few demographics are not actively harmed by the regulation.

More recently, an analysis of 15 proposed or final agency rules from the first 18 months of the Biden Administration found little improvement in the intervening decade.25Richard L. Revesz & Burçin Ünel, Just Regulation: Improving Distributional Analysis in Agency Rulemaking 3 (Ecology L. Q., Working Paper No. 23-26, 2023), https://ssrn.com/abstract=4314142. The study found agencies seldom consider distributional consequences of proposed rules and even more rarely consider distributional consequences of alternative rules.26Id. at 11. When agencies did look at distributional consequences, they only performed baseline analyses of the pre-rule status quo and suggested the proposed rule would benefit disadvantaged communities.27Id. The examination of alternatives is one of the foundational elements of analysis identified by Circular A-4 (2003).28Circular A-4 (2003) at 2 (the other key elements are “a statement of the need for the proposed action” and “an evaluation of the benefits and costs.”). Without an analysis of alternatives, agencies cannot genuinely weigh better distributional consequences of one proposed regulation against the higher net benefits of another, making distributional analysis little more than a rubber stamp on the proposed regulation.29Revesz, supra note 25 at 23.

Disregarding distributional effects can lead not just to ineffective, but harmful regulation. Traditional CBA relies on monetary values to compare costs and benefits, regardless of how much utility (or disutility) recipients of benefits and burdens actually receive.30Circular A-4 (2003) at 10. Frank Ackerman and Lisa Heinzerling, in an analysis of agency CBA practice, argue “[i]f decisions are based strictly on cost-benefit analysis and willingness to pay, most environmental burdens will end up being imposed on the countries, communities, and individuals with the least resources.”31Frank Ackerman & Lisa Heinzerling, Pricing the Priceless: Cost-Benefit Analysis of Environmental Protection, 150 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1553, 1575 (2002). As such, the “fundamental defect of cost-benefit analysis is that it tends to ignore, and therefore has the effect of reinforcing, patterns of economic and social inequality.”32Id .at 1573. Melissa J. Luttrell and Jorge Roman-Romero argue that reliance on CBA undermines policies and statutes meant to address disparities by “by ignoring—or dramatically undervaluing—equity concerns” and “by promoting weak health, safety, and environmental standards.”

It is into this context that President Biden issued a memorandum in January 2021 on “Modernizing Regulatory Review.”33Modernizing Regulatory Review, 86 Fed. Reg. 7223 (Jan. 26, 2021). This memorandum directs OMB to revise Circular A-4 and “propose procedures that take into account the distributional consequences of regulations, including as part of any quantitative or qualitative analysis of the costs and benefits of regulations, to ensure that regulatory initiatives appropriately benefit and do not inappropriately burden disadvantaged, vulnerable, or marginalized communities.”34Id. A little over two years later, following the confirmation of Richard Revesz as the new Administrator of OIRA, the office proposed the first revision to Circular A-4 in 20 years.35Circular A-4 (2023).

The proposed draft of Circular A-4 (2023) represents an overhaul of how regulatory analysis should treat distributional effects. A-4 (2003) spent only two paragraphs discussing distributional analysis — the first explained what distributional analysis is and the second gave vague recommendations to agencies to engage in distributional analysis when distributional effects “are thought to be important.”36Circular A-4 (2003) at 14. A-4 (2023) dedicates five pages to explaining distributional analysis in detail.37Circular A-4 (2023) at 61-66. Perhaps the most significant change is the explicit endorsement of income weighting.38Id. at 65. As the next section discusses, income weighting should bolster rationality and equity in regulatory decisions by directing more benefits and fewer burdens to low-income communities.

II. Income Weighting in Circular A-4 (2023)

Regulatory analysis and CBA have always proceeded on the irrational assumption that a dollar of benefits or burdens is worth the same to everyone.39Id. at 65; Matthew D. Adler, Benefit–Cost Analysis and Distributional Weights: An Overview, 10 Rev. Envtl. Econ. & Pol’y 264, 264 (2016) (“BCA does not take into account whether those made better off by a policy have higher or lower incomes, or higher or lower levels of nonincome welfare-relevant attributes (e.g., health), than those made worse off.”). A-4 (2023) rectifies this error, allowing agencies to use distributional weights to account for the diminishing marginal utility of income.40Circular A-4 (2023) at 65. While this choice is not uncontroversial, income weighting should make regulatory analysis more rational by incorporating well-established economic principles on social welfare and more equitable by encouraging the deployment of regulatory benefits to low-income communities and individuals.

A. Income Weighting Will Make Regulatory Analysis More Rational and Equitable

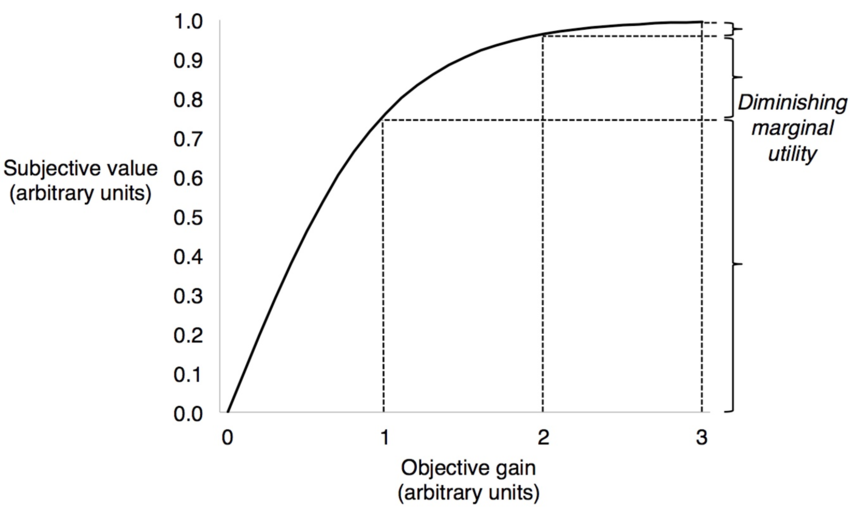

In economics, the law of diminishing marginal utility posits that “each additional unit of gain leads to an ever-smaller increase in subjective value” (see Fig. 1 for a graphical illustration of this concept).41E.T. Berkman, L.E. Kahn, J.L. Livingston, Valuation as a Mechanism of Self-Control and Ego Depletion within Self-Regulation and Ego Control (Academic Press 2016) 255, 265-66. When applied to money, this means that identical increases in income for a poor person and a wealthy person provide less utility to the latter because the utility associated with marginal increases in income decrease as total income increases.42Gregory M. Mikkelson, Diversity and the Good, in Handbook of the Philosophy of Science, 406 (2011). Put another way: “$1,000 in the hands of a destitute person would add significantly to that person’s utility. In contrast, that money would add very little, if any, utility to Jeff Bezos.”43Revesz, supra note 10 at 94. In the context of regulatory analysis, an additional dollar of benefit or burden to a poor person is worth more than the same benefit or burden to a wealthy person.

This law of diminishing marginal utility can be functionalized through a social welfare function. Social welfare functions are mathematical models that measure well-being based on the distribution of a utility (such as income) in response to policy interventions.44Adler, supra note 39. Income weighting is a social welfare function in which the value of costs and benefits factor in the income of those benefitted or burdened.45Fleurbacey, supra note 11, at 286. Social welfare functions can also be applied to non-income utility measures, such as health or environmental quality, but those are more difficult to measure and operationalize.46Lienke, supra note 11 at 19.

Fig. 1, illustrating the concept of diminishing marginal utility47Berkman, supra note 41.

A-4 (2023) draws on a strong pedigree of economics and social welfare research in recommending the use of an income-based social welfare function. Distributional weights have been described since at least the 1950s,48Adler, supra note 39. but have never been endorsed by U.S. federal officials (though they have been used by the World Bank and regulators in the United Kingdom).49Id. While prior CBAs have not explicitly engaged with income weighting, A-4 (2023) recognizes that all CBAs inherently include income weights.50Circular A-4 (2023) at 65. Omitting an explicit income weight simply assumes benefits and burdens are worth the same to everyone, which is an income weight of 1. Thus, A-4 (2023) refers to this method as “traditionally-weighted estimates” rather than “’unweighted’ estimates.”51Id.

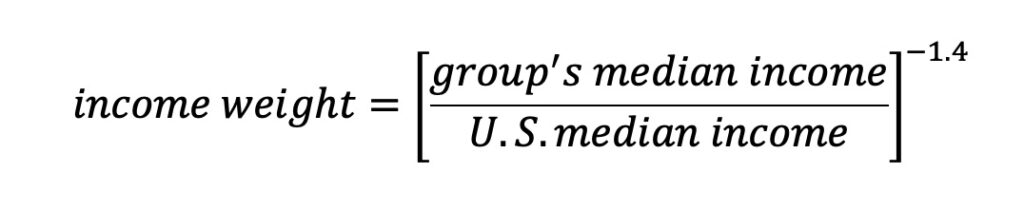

However, for the reasons discussed above, a weight of 1 is an irrational weight. As such, A-4 (2023) suggests agencies consider using weights “for each income group affected by a regulation.”52Office of Mgmt. & Budget, Preamble: Proposed Circular No. A-4, ‘Regulatory Analysis’ 12 (2023) [hereinafter Circular A-4 (2023) Preamble]. The weight would “equal the median income of the group divided by median U.S. income, raised to the power of the elasticity of marginal utility times negative one.”53Id. The elasticity of marginal utility is the rate at which utility varies based on income (how “elastic” it is).54Disa Asplund, Household Production and the Elasticity of Marginal Utility of Consumption, 17 B.E. J. of Econ. & Pub. Pol’y 2 (2017). In formulating this function, OMB surveyed the literature and took the mean of nine different studies’ calculation of the elasticity of marginal utility, arriving at a value of 1.4.55Circular A-4 (2023) Preamble at 12-15. The formula is as follows:

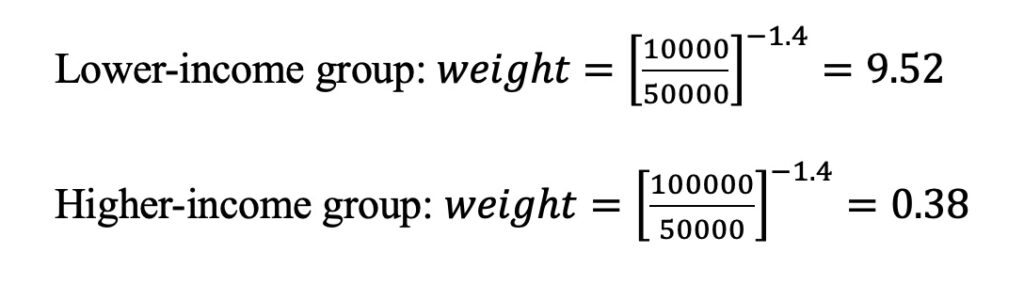

To illustrate what this means, we can use some simple numbers as an example. Let’s say the U.S. median income is $50,000 and a proposed regulation will distribute $100 in benefits to two equal-sized groups: one with a median income of $10,000 and another with a median income of $100,000.

This means that, for the lower income group, the $100 benefit would be multiplied by 9.52, resulting in a weighted benefit of $952. For the higher income group, the $100 benefit would be multiplied by 0.38, resulting in a weighted benefit of $38. In this simplified example, the benefit to the lower income group is worth about 25 times more than the benefit to the higher income group.

Executive Orders 12,866 and 13,563 both command agencies to consider regulatory alternatives and choose the approach that maximizes net benefits.56Exec. Order No. 12,866 § 1(a), 58 Fed. Reg. 190 (Sept. 30, 1993); Exec. Order No. 13,563 § 1(b), 76 Fed. Reg. 3821 (Jan. 21, 2011). The use of income weighting will result in very different regulatory approaches maximizing net benefits. In the above example, using traditional weighting, a costless regulation that distributed $100 in benefit to both groups, an alternative that distributed $200 to the wealthier group and $0 to the lower-income group, and a regulation that distributed $200 to the lower-income group and $0 to the wealthier group would all look the same. However, with income weighting, the option that distributes $200 to the lower-income group and $0 to the wealthier group would be far and away the option that maximizes net benefits. Traditional CBA, by ignoring income weights, does not capture the actual utility of those burdened and benefitted and therefore cannot accurately determine whether total utility has increased. If agencies systematically use income weighting in CBAs, the design of regulation could shift substantially, increasing equity by directing more benefits to lower income groups. However, the key question then becomes whether income weighting will be used as both a practical and legal matter.

B. Legal and Practical Constraints May Diminish the Use of Income Weighting

Circular A-4 (2023) does not require income weighting; it does not even seem to recommend it.57Circular A-4 (2023) at 65 (“Agencies may choose to conduct a benefit-cost analysis that applies weights to the benefits and costs accruing to different groups in order to account for the diminishing marginal utility of goods when aggregating those benefits and costs.”) (emphasis added). Rather, it simply presents it to agencies as an option.58Id. Thus, as a practical matter, it is possible that income weighting will simply never be used, much as distributional analysis writ large has gone largely unused despite its presence in Circular A-4 for 20 years. Furthermore, as courts have become increasingly antagonistic to the regulatory state, a novel (at least in the U.S. context) mechanism such as income weighting could pose a legal liability that stymies its use.

While agencies have been reticent to engage in distributional analysis, in at least some circumstances, agencies may be incentivized to use income weighting without OIRA needing to recommend it more aggressively. Any regulations in which benefits are distributed more to those with lower incomes and in which costs are distributed more to those with higher incomes should appear even more net beneficial when income weighting is used. Given the command in A-4 (2003) and (2023) to maximize net benefits, agencies may have an easier time showing that benefits have been maximized by using income weighting. Thus, agencies should be drawn to use income weighting in at least some of their regulations on its own merits. However, OIRA may need to actively encourage the use of income weighting to analyze a wider range of regulatory proposals.

Beyond not mandating income weighting, OIRA appears to be hedging its bets further: if an agency does choose to use income weighting in its analysis, it must still present a CBA with the traditional income weight of 1.59Id.59 This may be an effort to protect against any potential legal liability of income weighting, as it is an untested methodology in U.S. administrative law.60Revesz, supra note 10 at 94. As Administrator Revesz has previously cautioned, since there is not a preexisting method for incorporating income weights into regulatory analysis that has been blessed by the courts, “any choice of a social welfare function could prove controversial and be the focus of challenges in court to any rules that were justified by reference to such functions.”61Id.

In a legal environment in which courts appear increasingly averse to the regulatory state generally, income weighting could provide judges a reason to invalidate regulations. A court could align with criticisms of OMB’s calculation of the elasticity of marginal utility. Legal avenues of attack are magnified if a regulation only appears net beneficial when using income weights that incorporate the decreasing marginal utility of income (i.e., income weights not equal to 1). The Supreme Court has previously stated that “[n]o regulation is ‘appropriate’ if it does significantly more harm than good.”62Michigan v. EPA, 576 U.S. 743, 752 (2015). If a regulation only appears beneficial when using income weights not equal to 1 (e.g., if it directs benefits to low income groups and imposes cost on high income groups, but in standard dollar amounts the costs exceed the benefits), then opponents of said regulation could argue it violates the Administrative Procedure Act by, in some sense, doing more harm than good.

These are untested waters and innovation can often meet hostile responses from a judiciary predisposed to be skeptical or outright hostile to the regulatory state. Of even greater concern, should the Chevron doctrine be eliminated or curtailed in the forthcoming Supreme Court case Loper Bright Enterprises v. Riamondo, courts may accord agencies less deference in determining whether a statute allows for cost-benefit analysis or income weighting in the first place.6345 F.4th 359 (D.C. Cir. 2022), cert. granted (U.S. May 1, 2023) (No. 22-451). If the ability to use a CBA is restricted as a result, income weighting could become a non-starter.

C. Criticisms of Income Weighting

Even if agencies do engage in income weighting properly and regularly and if courts do not use it as an excuse to overturn regulations, there are nevertheless criticisms of the very use of income weighting. A full accounting of all counterarguments to income weighting is beyond the scope of this article. However, this section serves to highlight a few of the major reasons why agencies may reasonably hesitate to use income-weighted CBAs even if they are able to do so as both a practical and legal matter.

One criticism is that income weighting may provide more limited guidance than it appears. As Richard Revesz argued, income weighting will generally only lead to changes within the scope of the regulation.64Revesz, supra note 9 at 1570. Income weighting cannot account for measures that would mitigate regressive distributional effects through other agency actions or even through measures outside the agency.65Id.65 Coordinated regulatory action with another agency, other levers of redistribution such as taxation, or the actions of another branch of government, such as Congress, could all serve to address the perhaps regressive but net beneficial results of a regulation.66Id. Agencies must understand that income weighting is an analytical tool internal to the regulatory proposal and its alternatives, and should not be blinded to possible mitigating measures beyond the scope of the regulation.

Some have argued that traditional CBA is in fact a better tool, despite the diminishing marginal utility of income. Daniel Hemel argues that “the status quo approach . . . makes practical sense in light of expressive concerns, informational burdens, and institutional constraints.”67Daniel Hemel, Regulation and Redistribution with Lives in the Balance, 89 U. Chi. L. Rev. 649, 650 (2022). Hemel cautions that income weighting could lead to irrational results, giving the wellbeing of lower income individuals far greater weight than the wellbeing of higher income individuals.68Id. at 712. He argues that the traditional CBA strikes the best balance of expressivity concerns, rationality, and workability.

Additionally, some argue that the tax system is inherently better equipped to address distributional concerns than environmental, health, and safety regulations.69Id. at 730. David Weisbach argues that, fundamentally, agencies are not meant to nor equipped to redistribute wealth or benefits or even to maximize welfare; they are meant to “perform specialized tasks” such as regulating pollution or workplace safety.70David A. Weisbach, Distributionally Weighted Cost-Benefit Analysis: Welfare Economics Meets Organizational Design, 7 J. Legal Analysis 151 (2015). Weisbach argues that the tax-and-transfer system is the best tool for addressing distributional concerns: “it is less efficient to redistribute through modifications to regulatory rules than to achieve the same level of redistribution directly by taxing the wealthy more or the poor less.”71Id. at 152.

Reasonable minds can differ on all these issues. Perhaps that is another reason OIRA has not mandated income weighting, but merely presented it as an option to agencies. There may be instances where income weighting makes more sense than others. The very fact that those with lower incomes will generally derive greater economic utility from certain benefits than those with higher incomes provides a strong theoretical foundation for income weighting. Furthermore, to the extent that the use of income weighting leads to more benefits being directed to those with lower incomes, the progressive distributional effects may outweigh some of the above concerns, even if there are limits to the usefulness of income weighting or if other tools (such as taxation) could accomplish redistribution more efficiently.

Conclusion

Circular A-4 (2023) is a vast improvement upon its predecessor in almost every way. It specifically bolsters distributional analysis guidance by providing agencies the option of using income weighting, advising agencies to perform analysis of alternatives, and explicitly allowing agencies to advance regulations that do not maximize net benefits if the distributional effects of an alternative outweigh the foregone benefits. The use of income weighting should lead to regulations that are more rational (by incorporating the law of diminishing marginal utility of income) and more equitable (by directing greater regulatory benefits and fewer regulatory burdens to lower income groups). A-4 (2023) still preserves a great deal of agency discretion, so the effect of this new guidance will ultimately be borne out in practice. It remains to be seen whether agencies will use distributional analysis or if it will continue to be an unused tool of regulatory analysis and review, but A-4 (2023) has the potential to improve both regulatory analysis and the lives of countless Americans that benefit from regulation.

Kyle McKenney, J.D. Class of 2024, N.Y.U. School of Law.

Suggested Citation: Kyle McKenney, Updating Circular A-4: How Adding Income Weighting to Decades-Old Guidance Could Make Government Regulations More Rational and Equitable, N.Y.U. J. Legis. & Pub. Pol’y Quorum (2023).

- 1Office of Mgmt. & Budget, Circular A-4: Regulatory Analysis, Draft for Public Review (2023) [hereinafter Circular A-4 (2023)].

- 2Office of Mgmt. & Budget, Circular A-4: Regulatory Analysis 14 (2003) [hereinafter Circular A-4 (2003)].

- 3Exec. Order 12,898, 59 Fed. Reg. 31 (Feb. 16, 1994) (directing federal agencies to identify and address the disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of regulatory actions on minority and low-income populations).

- 4Request for Comments on Proposed OMB Circular No. A–4, ‘‘Regulatory Analysis,” 88 Fed. Reg. 20915, (April 7, 2023). Henceforth, the two versions of Circular A-4 will be distinguished. as Circular A-4 (2003) and Circular A-4 (2023).

- 5Circular A-4 (2003) at 10.

- 6Id.

- 7Circular A-4 (2023) at 61.

- 8Exec. Order No. 12,866, §§ 1(a), (b)(5), 58 Fed. Reg. 190 (Sept. 30, 1993).

- 9See Richard L. Revesz, Regulation and Distribution, 93 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1489, 1491 (2018).

- 10Richard L. Revesz & Samantha P. Yi, Distributional Consequences and Regulatory Analysis, 52 Envtl. Rev. 53, 55 (2022).

- 11See H. Spencer Banzhaf et al., Environmental Justice: Establishing Causal Relationships, 11 Ann. Rev. Res. Econ. 377, 379 (2019); see Jack Lienke et al., Making Regulations Fair: How Cost-Benefit Analysis Can Promote Equity and Advance Environmental Justice, Inst. for Pol’y Integrity 4 (2021). The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) noted over 30 years ago that “[r]acial minority and low-income populations experience higher than average exposures to pollutants, hazardous waste facilities, contaminated fish and agricultural pesticides in the workplace.” Env’t Prot. Agency (hereinafter, EPA), Environmental Equity: Reducing Risk for All Communities 3 (June 1992).

- 12Circular A-4 (2023) at 65-66.

- 13Marc Fleurbaey & Rossi Abi-Rafeh, The Use of Distributional Weights in Benefit-Cost Analysis: Insights from Welfare Economics, 10 Rev. Envtl. Econ. & Pol’y 286, 286 (2016).

- 14Exec. Order No. 13,985 § 1, 86 Fed. Reg. 7009 (Jan. 20, 2021).

- 15Revesz, supra note 10 at 53.

- 16Exec. Order No. 12,866 §§ 1(a), (b)(5).5, 58 Fed. Reg. 190 (Sept. 30, 1993).

- 17Compare Exec. Order No. 13,563 §§ 1(b)-(c), 76 Fed. Reg. 3831 (Jan. 21, 2011) with Exec. Order No. 12,866 §§ 1(a), (b)(5).5, 58 Fed. Reg. 190 (Sept. 30, 1993).

- 18Exec. Order No. 12,866 § 2(b), 58 Fed. Reg. 190 (Sept. 30, 1993); Exec. Order No. 13,563 § 6(b), 76 Fed. Reg. 3831 (Jan. 21, 2011).

- 19Revesz, supra note 10.

- 20Lisa A. Robinson et al., Attention to Distribution in U.S. Regulatory Analyses, 10 Rev. Env’t Econ. & Pol’y 308, 314-16 (2016).

- 21Id. at 311.

- 22Id. at 313.

- 23Id. at 314.

- 24Id. at 313.

- 25Richard L. Revesz & Burçin Ünel, Just Regulation: Improving Distributional Analysis in Agency Rulemaking 3 (Ecology L. Q., Working Paper No. 23-26, 2023), https://ssrn.com/abstract=4314142.

- 26Id. at 11.

- 27Id.

- 28Circular A-4 (2003) at 2 (the other key elements are “a statement of the need for the proposed action” and “an evaluation of the benefits and costs.”).

- 29Revesz, supra note 25 at 23.

- 30Circular A-4 (2003) at 10.

- 31Frank Ackerman & Lisa Heinzerling, Pricing the Priceless: Cost-Benefit Analysis of Environmental Protection, 150 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1553, 1575 (2002).

- 32Id .at 1573.

- 33Modernizing Regulatory Review, 86 Fed. Reg. 7223 (Jan. 26, 2021).

- 34Id.

- 35Circular A-4 (2023).

- 36Circular A-4 (2003) at 14.

- 37Circular A-4 (2023) at 61-66.

- 38Id. at 65.

- 39Id. at 65; Matthew D. Adler, Benefit–Cost Analysis and Distributional Weights: An Overview, 10 Rev. Envtl. Econ. & Pol’y 264, 264 (2016) (“BCA does not take into account whether those made better off by a policy have higher or lower incomes, or higher or lower levels of nonincome welfare-relevant attributes (e.g., health), than those made worse off.”).

- 40Circular A-4 (2023) at 65.

- 41E.T. Berkman, L.E. Kahn, J.L. Livingston, Valuation as a Mechanism of Self-Control and Ego Depletion within Self-Regulation and Ego Control (Academic Press 2016) 255, 265-66.

- 42Gregory M. Mikkelson, Diversity and the Good, in Handbook of the Philosophy of Science, 406 (2011).

- 43Revesz, supra note 10 at 94.

- 44Adler, supra note 39.

- 45Fleurbacey, supra note 11, at 286.

- 46Lienke, supra note 11 at 19.

- 47Berkman, supra note 41.

- 48Adler, supra note 39.

- 49Id.

- 50Circular A-4 (2023) at 65.

- 51Id.

- 52Office of Mgmt. & Budget, Preamble: Proposed Circular No. A-4, ‘Regulatory Analysis’ 12 (2023) [hereinafter Circular A-4 (2023) Preamble].

- 53Id.

- 54Disa Asplund, Household Production and the Elasticity of Marginal Utility of Consumption, 17 B.E. J. of Econ. & Pub. Pol’y 2 (2017).

- 55Circular A-4 (2023) Preamble at 12-15.

- 56Exec. Order No. 12,866 § 1(a), 58 Fed. Reg. 190 (Sept. 30, 1993); Exec. Order No. 13,563 § 1(b), 76 Fed. Reg. 3821 (Jan. 21, 2011).

- 57Circular A-4 (2023) at 65 (“Agencies may choose to conduct a benefit-cost analysis that applies weights to the benefits and costs accruing to different groups in order to account for the diminishing marginal utility of goods when aggregating those benefits and costs.”) (emphasis added).

- 58Id.

- 59

- 60

- 61Id.

- 62Michigan v. EPA, 576 U.S. 743, 752 (2015).

- 6345 F.4th 359 (D.C. Cir. 2022), cert. granted (U.S. May 1, 2023) (No. 22-451).

- 64Revesz, supra note 9 at 1570.

- 65

- 66

- 67Daniel Hemel, Regulation and Redistribution with Lives in the Balance, 89 U. Chi. L. Rev. 649, 650 (2022).

- 68Id. at 712.

- 69Id. at 730.

- 70David A. Weisbach, Distributionally Weighted Cost-Benefit Analysis: Welfare Economics Meets Organizational Design, 7 J. Legal Analysis 151 (2015).

- 71Id. at 152.