By: Nick Lussier

December 22, 2021

There are 1.1 million doctors in the United States and just about half of them have received some form of remuneration from pharmaceutical companies.1Remuneration can include gifts as mundane as pens and pads of paper, food and beverage, “honoraria” payments (which are payments for certain kinds of consulting services), lodging, and expensive travel. See Charles Ornstein et al., We Found Over 700 Doctors Who Were Paid More Than a Million Dollars by Drug and Medical Device Companies, ProPublica (Oct. 17, 2019, 12:00 PM), https://www.propublica.org/article/we-found-over-700-doctors-who-were-paid-more-than-a-million-dollars-by-drug-and-medical-device-companies; Triangle et al., Types and Distributions of Payments From Industry to Physicians in 2015, JAMA. 2017 May 2;317(17):1774-1784 (May 2017), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28464140/. It is well established that remuneration provided to doctors by pharmaceutical companies influences prescribing,2Puneet Manchanda & Elisabeth Honka,The Effects and Role of Direct-to-Physician Marketing in the Pharmaceutical Industry: An Integrative Review, 5 Yale J. Health Pol’y L. & Ethics 785 (2005), https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1127&context=yjhple; Susan F. Wood et al., Influence of Pharmaceutical Marketing on Medicare Prescriptions in the District of Columbia, PLOS ONE (Oct. 25, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186060; Elliot Morse et al., The Association Between Industry Payments and Brand-Name Prescriptions in Otolaryngologists, 161 J. Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery 605 (2019). even when the medication is costly or of questionable medical benefit.3Manvi Sharma et al., Association Between Industry Payments and Prescribing Costly Medications: An Observational Study Using Open Payments and Medicare Part D Data, BMC Health Servs. Res. (Apr. 2018), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324211217_Association_between_industry_payments_and_prescribing_costly_medications_An_observational_study_using_open_payments_and_medicare_part_D_data (to access, follow the “Download full-text PDF” hyperlink); Freek Fickweiler et al., Interactions Between Physicians and the Pharmaceutical Industry Generally and Sales Representatives Specifically and Their Association with Physicians’ Attitudes and Prescribing Habits: A Systematic Review, BMJ Open (Sept. 17, 2017), https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/7/9/e016408.full.pdf. Indeed, the inducement transcends gifts (like notepads or pens) and covers payments for services as well.4Roy H. Perlis & Clifford S. Perlis, Physician Payments from Industry Are Associated with Greater Medicare Part D Prescribing Costs, PLOS ONE (May 16, 2016), https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155474. Critically, health care professionals often see themselves as immune from such influence, yet suspect others might be susceptible.5Edward C. Halperin et al., A Population-Based Study of the Prevalence and Influence of Gifts to Radiation Oncologists from Pharmaceutical Companies and Medical Equipment Manufacturers, 59 Int’l J. Radiation Oncology Biology Physics 1477 (2004), doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.01.052, PMID: 15275735. That is, they acknowledge the corrupting influence a payment might carry with it, but see it as someone else’s problem. Therefore, a strange bias in the medical community actually rationalizes the behavior of gift-receiving doctors who do not question the practice of pharmaceutical gift giving.6S. Madhavan et al., The Gift Relationship Between Pharmaceutical Companies and Physicians: An Exploratory Survey of Physicians, 22 J. Clinical Pharmacy & Therapeutics 207 (1997). Despite academic and legal scrutiny, the practice of providing gifts or compensation to doctors is growing.7See Orenstein et al., supra note 1. As of 2019, at least 700 doctors have individually made more than $1 million from pharmaceutical companies–a 175-fold increase since 2013.8Id.

The Sunshine Act

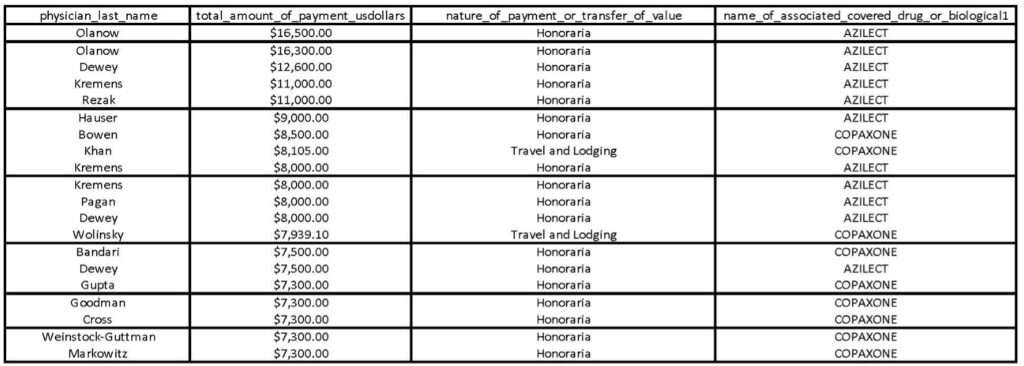

In 2010, Congress attempted to “shine a light” on payments made to certain medical professionals by passing the Physician Payments Sunshine Act (“PPSA”) requiring medical product manufacturers to disclose any payments made to physicians or teaching hospitals to the government.9 42 U.S.C. Code § 1320a-7h.The data is published annually on a website maintained by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”), called Open Payments.10The database can be searched here: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov. The data can be helpful to determine how remuneration an individual doctor, perhaps even your own doctor, recieves from pharmaceutical company marketing initiatives.11See, e.g., Teva Pharmaceuticals, Open Payments, https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/company/100000000141. Here is an example of data from Open Payments:12This is a spreadsheet downloaded from Open Payments showing the expenditures made for Copaxone or Azilect by Teva Pharmaceuticals in 2014. The spreadsheet generated from Open Payments includes approximately 33 columns, many of which are irrelevant to the scope of this article (e.g. the date of the payment, the address of the receiving party, etc). If you are interested, you can download the full dataset from https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/company/100000000141.

Critically, despite the above chart being edited for clarity, none of the information contained in the Open Payments data provides granular data about the nature of the payments. Taking Dr. Wolinsky in the chart above as an example, there is no way to know whether the travel and lodging provided includes a first-class ticket to Miami for a stay in a suite of the Four Seasons, or if they simply stayed in several motels with exorbitant holiday travel costs imposed over the course of a week or two. So, while the PPSA is a great step in the right direction, it is lacking in several critical respects exemplified in several civil lawsuit enforcement actions initiated in the last decade.

Marketing the Drug

Before digging into the enforcement actions, it is important to understand how pharmaceutical marketing works. Pharmaceutical marketing is complex and costly. At the turn of the century, pharmaceutical companies were spending $15.7 billion marketing their drugs.13Adriane Fugh-Berman & Shahram Ahari, Following the Script: How Drug Reps Make Friends and Influence Doctors, PLOSMEDICINE (2007), https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.0040150&type=printable. Since then, perhaps unsurprisingly, drug manufacturers have doubled down and accelerated spending. Pharmaceutical companies spent approximately $25 billion on pharmaceutical marketing in 2012 alone.14Persuading the Prescribers: Pharmaceutical Industry Marketing and Its Influence on Physicians and Patients, The Pew Charitable Trusts (Nov. 11, 2013), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2013/11/11/persuading-the-prescribers-pharmaceutical-industry-marketing-and-its-influence-on-physicians-and-patients.

We all know the commercials – the endless ones with disclaimers almost as long as the commercial themselves. We may even have seen a poster or leaflet in our doctors’ offices. In truth, these direct-to-consumer advertisements represent approximately 20 percent of pharmaceutical marketing budgets nationwide.15Id. The majority of pharmaceutical marketing is the stuff you never see – here, the proverbial sausage gets made through expenditures fostering personal interactions with physicians. One example is detailing – also colloquially referred to as “a call” – which is when a pharmaceutical sales representative physically goes into a doctor’s office to talk about the drug.16It is well-known that some pharmaceutical sales representatives fake their calls, see, e.g., Anonymous, How Many FAKE Calls You Make a Day?, Cafepharma: Daiichi-Sankyo (Mar. 19, 2014), http://www.cafepharma.com/boards/threads/how-many-fake-calls-you-make-a-day.553719/; Anonymous, Fake Calls – Enough Is Enough!!!!!!!!, Cafepharma: AstraZeneca (May. 12, 2012), http://www.cafepharma.com/boards/threads/fake-calls-enough-is-enough.501743/; Anonymous, HOW MANY FAKE CALLS DO YOU FAKE EACH DAY?, Cafepharma: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Apr. 3, 2011), http://www.cafepharma.com/boards/threads/how-many-calls-do-you-fake-each-day.462063/page-2. Nearly $8 billion is spent on tactics including providing free samples, sponsoring Continuing Medical Education events, and controversially, Speaker Programs.”17The Pew Charitable Trusts, supra note 14.

Speaker Programs: Peer-to-Peer and Patient Programs

Speaker Programs come in two different forms, “Peer-to-Peer” and “Patient Programs.” Peer-to-Peer programs involve a doctor being paid to present a slide presentation, over a meal, to an audience ideally comprised of other health care providers likely to prescribe the presented drug.18Pharmaceutical companies have spent billions on “compensation for services other than consulting, including serving as faculty or as a speaker at a venue other than a continuing education program” for years 2017, 2018, and 2019 combined. Open Payments Complete 2017, 2018, and 2019 Program Year Datasets, CMS, https://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/Explore-the-Data/Data- Overview (accessed Sept. 9, 2020). By contrast, Patient Programs, another form of direct-to-consumer marketing like television ads, involve a paid speaker presenting drug information to patients. For both Peer-to-Peer and Patient Programs, speakers receive a fee commensurate to their medical experience. So far, so good. Right?

As detailed below, pharmaceutical companies have abused Speaker Programs as a means of rewarding high-prescribing doctors and as leverage to make doctors maintain or increase their prescriptions of company drugs. Such programs may not even be informative. Many take place in opulent venues with lavish meals and presentations that teach the audience nothing of substance – if there is even an audience.19See Plaintiff-Relators’ Mot. Opp’n Summ. J. at 21, Dkt. # 135, United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals 1:13-cv-0702 (CM), September 13, 2018.

Enforcement Actions: Novartis, Teva, and Gilead

Recently, Speaker Programs have come under intense scrutiny. The federal government has probed several companies for misconduct under the False Claims Act and Anti-Kickback Statute. In 2020, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York settled two cases alleging that Speaker Programs served as the conduit through which two pharmaceutical companies, Novartis and Teva, paid physicians kickbacks to influence prescribing habits.20Jaclyn Jaeger, Teva to Pay $54M in FCA Whistleblower Settlement, Compliance Week (Jan. 7, 2020, 3:01 PM), https://www.complianceweek.com/whistleblowers/teva-to-pay-54m-in-fca-whistleblower-settlement/28281.article; Press Release, U.S. Att’y’s Off. S.D.N.Y., Acting Manhattan U.S. Attorney Announces $678 Million Settlement of Fraud Lawsuit Against Novartis Pharmaceuticals for Operating Sham Speaker Programs Through Which It Paid Over $100 Million to Doctors to Unlawfully Induce Them to Prescribe Novartis Drugs (July 1, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/acting-manhattan-us-attorney-announces-678-million-settlement-fraud-lawsuit-against. Together, the two cases represented nearly 40 percent of the Department of Justice’s total recovery under the False Claims Act in 2020.21Press Release, Dep’t Just. Off. Pub. Affs., Justice Department Recovers Over $2.2 Billion from False Claims Act Cases in Fiscal Year 2020 (Jan. 14, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-recovers-over-22-billion-false-claims-act-cases-fiscal-year-2020. A third case in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania against Gilead settled in 2021.22Order in Purcell v. Gilead, Dkt. # 282, 2:17-cv-03523 (MAK), July 28, 2021. Each of the three cases focused on four aspects of a companies’ nationwide speaker program scheme: (1) the sheer number of programs conducted; (2) evidence of an intent to induce or reward prescribers; (3) lavish food, venues, and entertainment; and (4) the lack of educational content in the program presentations. At least with respect to Novartis and Teva, the government unearthed evidence of tens of thousands of sham speaker programs.23See United States ex rel. Bilotta v. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Dkt. # 50 1:11-v-00071, July 10, 2013; United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Third Amended Complaint, Dkt. # 53, March 23, 2016; United States ex rel. Purcell et al. v. Gilead, Fourth Amended Complaint, Dkt. # 118, September 30, 2020.

Novartis

The Novartis case alleged a nationwide kickback scheme to induce physicians to prescribe the cardiovascular drugs Lotrel, Diovan, and Exforge, among others. The government alleged Novartis conducted 525,000 programs between January 2002 and November 2011, amounting to nearly 100 programs per day.24Government Mot. Opp’n Summ. J. at 11, Dkt. # 230, 1:11-cv-00071, August 29, 2018. Each speaker was paid between $500 and $2,000 per event, putting the total expenditure on Speaker Programs in the hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars.25Id. at 12.

One Novartis sales representative testified that “the “primary purpose of speaker programs and roundtables was to keep the doctors happy— by paying them honoraria and treating them to meals, often at high-end restaurants—so they would write prescriptions for Novartis drugs.”26Id. So, the Government alleged that Novartis, to make the doctors happy, took doctors and their spouses to dinner, hosted dozens of supposedly educational programs at Hooters, organized “Happy Hours” for doctors and their staff, and let physicians attend programs with their friends in clusters.27The Government alleged that doctors would attend programs together and “take turns” speaking to each other, even though their audience was comprised of speakers who were trained to speak on the very same presentation they were hearing. Id. In their opposition to summary judgment, the Government noted one cluster that attended 34 programs together in a single year. Id.; see also Stipulation and Order of Dismissal, Dkt. # 342 at 11, 1:11-cv-00071, July 21, 2020 (Novartis admitted “[i]n thousands of instances, Novartis paid for the same group of doctors, often colleagues or friends, to have dinners together repeatedly (along with other doctors or health care providers on occasion). Doctors in these groups would sometimes rotate being the speaker and receiving the honorarium payment.” Despite the pharmaceutical industry’s own guidance explaining that Speaker Programs should be held at modest venues with occasional meals that are incidental to the program,28Code on Interactions with Health Care Professionals, PhRMA, https://www.phrma.org/-/media/Project/PhRMA/PhRMA-Org/PhRMA-Org/PDF/A-C/Code-of-Interaction_FINAL21.pdf (last visited Dec. 3, 2021). the Government described programs at venues like The Four Seasons hotel, Eleven Madison (a Michelin three-star restaurant in New York City), and Peter Luger (a historic Brooklyn steakhouse).29See Stipulation and Order of Dismissal, Dkt. # 342, 1:11-cv-00071, July 21, 2020. At such venues, it is perhaps unsurprising that dinner tabs were high. The Government found 6,500 programs where sales representative spent more than $250 per person.30The data is likely understated as the Government noted “sales representatives often doctored the paperwork associated with these events to reduce the average per person cost reflected in the data,” Stipulation and Order of Dismissal, Dkt. # 342 at 11, 1:11-cv-00071, July 21, 2020. Novartis, like the Pharmaceutical Industry writ large, defines a “modest meal” as $125 per person for dinner. Under that definition, an individual can have $50 steak, a $50 bottle of wine, tip 20% and still fall below the threshold. See United States ex rel. Bilotta v. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Dkt. # 50 1:11-v-00071, July 10, 2013; United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Third Amended Complaint, Dkt. # 53, March 23, 2016; United States ex rel. Purcell et al. v. Gilead, Fourth Amended Complaint, Dkt. # 118, September 30, 2020; see also David F. Essi, “Mixing Dinner and Drugs – Is it Ethically Contraindicated?,” American Med. J. of Ethics, August 2015, Volume 17, Number 8: 787-795. Novartis tried to infuse entertainment into its purportedly educational programs by conducting programs at venues like wineries, golf clubs, sports venues, and who can forget Hooters.31Stipulation and Order of Dismissal, Dkt. # 342 at 7, 1:11-cv-00071, July 21, 2020.According to the Government, they even invited non-health care professionals, undercutting the argument that these programs aimed to persuade practitioners to prescribe the drug.32Government Mot. Opp’n Summ. J. at 5, Dkt. # 230, 1:11-cv-00071, August 29, 2018. If doctors did not respond favorably to these inducements, Novartis personnel testified that they were often dropped as speakers – no fun if you do not play the game.33Id. at 19. In total, the Government found 95,000 physicians who received compensation from Novartis.34Id. at 2. Meanwhile the compliance department charged with monitoring all this activity was staffed by only one person in 2003.35Id. at 12.

The Novartis case culminated in a $600 million settlement with the United States.36Stipulation and Order of Dismissal, Dkt. # 342 at 11, 1:11-cv-00071, July 21, 2020. In that agreement, Novartis admitted to aspects of the alleged conduct, including conducting “more than 12,000 speaker programs and roundtables had meal spends that were considerably in excess of the $125 per person limit set by Novartis’s compliance policies.”37Id. at 7. Critically, Novartis also admitted to falsifying records that tended to understate how much was spent per doctor at events.38Id. Given such cover, Novartis admitted “doctors demanded expensive bottles of wine and “[d]octors sometimes consumed alcohol in large quantities at these events, to the point of intoxication.”39 Id. The social nature of these programs kept doctors coming back – much to Novartis’s chagrin – and repeat attendance drove prescription sales.40Novartis admitted “the ROI for doctors who attended more than one roundtable was 1,200%. Stipulation and Order of Dismissal, Dkt. # 342 at 8, 1:11-cv-00071, July 21, 2020. The Novartis case highlights the need for mandatory disclosures of such detailed information so consumers can discern for themselves whether their doctors are engaged in similarly suspect behavior.41There is another case pending against Novartis Pharmaceuticals alleging substantially similar conduct regarding its Multiple Sclerosis drug, Gilenya. See United States ex rel. Camburn v. Novartis Pharmaceuticals, 1:13-cv-03700, Third Amended Complaint, Dkt. # 77, November 19, 2021.

Non-Intervened Cases: Teva and Gilead

Non-intervened False Claims Act cases are cases in which the Government declines to take a lead role in prosecuting the case, but still receives a significant portion of the cash recovery. This is the opposite of an intervened case, where the Government spearheads the litigation. In the former circumstance, the “relator,” the private party who brought the case, litigates the case with legal counsel of his or her own. The Teva and Gilead cases were both litigated by a relator.

Like the Novartis case, the Teva case involved allegations of a nationwide kickback scheme regarding two of Teva’s branded drugs, Copaxone (Multiple Sclerosis) and Azilect (Parkinson’s Disease).42United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Third Amended Complaint, Dkt. # 53, March 23, 2016. This non-intervened case proceeded in the Southern District of New York and settled after Judge Colleen McMahon denied Teva’s Motion for Summary Judgment. It settled for $54 million. See Jaclyn Jaeger, “Teva to Pay $54 Million in FCA Whistleblower Settlement,” Compliance Week (Jan. 7, 2020), https://www.complianceweek.com/whistleblowers/teva-to-pay-54m-in-fca-whistleblower-settlement/28281.article. Part of Relators’ allegations focused on the fact Copaxone was nearly a twenty-year-old drug with little scientific development during the relevant time period.43United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Memorandum of Law in Opposition to Summary Judgment, Dkt. # 135, September 13, 2018. As such, the Relators’ argued Speaker Program were unnecessary because there was little (if any) new information to discuss with health care professionals.

Teva did not conduct nearly as many programs as Novartis, but their conduct was similarly problematic. For example, plaintiffs-relators alleged Teva conducted thousands of programs with one or zero attendees.44United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Memorandum of Law in Opposition to Summary Judgment, Dkt. # 135, September 13, 2018. Such an allegation indicates that speakers were paid thousands of dollars for simply showing up to an empty venue. Even Teva’s own Director of Compliance from 2006 to 2012 admitted that until at least 2009, local speaker programs were being conducted without monitoring by the Compliance Department.45United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Plaintiffs-Relators’ Rule 56.1 Counterstatement, Dkt. # 136 at 87, 1:13-cv-03702 (CM), September 13, 2018. Plaintiffs alleged the events were lavish. Indeed, they cited examples including one where there was a program with eight shots of Johnnie Walker Blue priced at $32.50 per shot.46Id. at 68. At another event, the program took place at a Miami nightclub on a Friday night with several shots of hard alcohol.47Id. In many instances the paid-speaker left before the event ended.48In 4 out of 30 audited programs, the independent monitor noted that the paid speaker left early. Id. at 69. Perhaps most damning, according to the Plaintiffs-relators’ allegations, often times speakers spoke to other speakers on the same drug with nobody else in attendance.49Id. at 51.Relators even alleged that Teva took certain high-prescribing doctors to the Super Bowl!50United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Memorandum of Law in Opposition to Summary Judgment, Dkt. # 135 at 22, September 13, 2018.Ultimately, this case settled for $54 million.51This non-intervened suit did not include admissions like the Novartis case.

The Gilead case proceeded in the same way as the two aforementioned cases but settled relatively early in litigation.52See Transcript of Oral Argument Held on June 25, 2021 before Judge Honorable Mark A. Kearney, Dkt. # 273, 2:17-cv-03523 (MAK)and Order in Purcell v. Gilead, Dkt. # 282, 2:17-cv-03523 (MAK), July 28, 2021. Plaintiffs-relators alleged that Gilead funneled millions of dollars of payments to various speakers, including over $100,000 to one high-prescriber of Gilead Hepatitis drugs Viread and Vemlidy.53United States ex rel. Purcell et al. v. Gilead, Fourth Amended Complaint, Dkt. # 118, September 30, 2020. Specifically, the plaintiffs alleged that Gilead leveraged speaker program payments to force doctors to transition doctors from their older drug Viread to their new drug, Vemlidy. Curiously, one doctor attended 26 programs in 2017 alone and received nearly $12,000 in food and lodging. Plaintiffs even catalogued an example of a doctor, through his spouse, requesting more programs so he could earn more money. Similarly, plaintiffs alleged one west coast doctor would routinely request speaker programs in New York City around Chinese New Year, presumably so he could visit his family at little to no personal cost.

Conclusion

Taken together, the cases of Novartis, Teva, and Gilead exemplify the need for greater public disclosures on physician remuneration by pharmaceutical manufacturers. As it stands, nobody can discern a suspicious payment from a legitimate one – the PPSA only sheds light on quantity, not quality. To combat the abuse of Speaker Programs, the PPSA should be amended to require the disclosure of details like restaurant venue, location of lodging, total expenditures per attendee, and detailed individual alcohol expenditures. Disclosures should include the identity and professional affiliation of the attendees, especially if they are not health care professionals. The rule would likely force sales representatives to arrange price-fixed meals without variation by attendee so as to minimize the logistical issues associated with documenting who ordered what meal. This would be a positive development as it would constrain otherwise vivacious guests from ordering, say, shots Johnnie Walker Blue. Critically, much of this is information is already collected by pharmaceutical companies and mandatory disclosure would not pose a great burden.54Indeed, that is how the allegations were made in Novartis, Teva, and Gilead. That is, the reason prosecutors knew many events happened at Hooters was because Novartis collected venue information (as did Teva and Gilead).

Updating the PPSA to address the abuse of Speaker Programs is necessary due to the public cost of such fraudulent inducements of health care providers. A prescription recommended by a doctor who would not have prescribed that medication but for the incentives offered by the manufacturer needs to be paid by someone. Often times the person paying is not an insurance company, but it is you and me as taxpayers. Medicare alone spent $370 billion on prescription drugs in 2019.55[3] NHE Fact Sheet, Ctrs. Medicare & Medicaid Servs., https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet (last updated Dec. 1, 2021).Thus the harm is not merely individual; it is borne by all of us.

But there is, perhaps, a greater public harm than cost. The healthcare system functions on trust. Doctors are experts in medicine. More times than not, patients do not possess the knowledge to question decisions made by their doctors. So, patients must believe their doctor is making the best decision for them. When that decision is made based on the quality of the speaker programs or remuneration offered by the manufacturer, rather than the patient’s medical needs, that trust is eroded. The continuation of pharmaceutical Speaker Programs, without greater disclosure and public scrutiny, threatens the foundation of our healthcare system.56Even if legislative action proves futile, there is hope. Recently amended to the PhRMA Code have prompted some commentators to question whether Speaker Programs will be a thing of the past. See Ropes & Gray, PhRMA Code 2022: Speaker Programs Enter a Prohibition Era? (Sept. 20, 2021), https://www.ropesgray.com/en/newsroom/alerts/2021/September/PhRMA-Code-2022-Speaker-Programs-Enter-a-Prohibition-Era.

Nick Lussier, J.D. Class of 2022, New York University School of Law

Suggested Citation: Nick Lussier, A Little More Sunshine: How to Improve the Sunshine Act in Light of Recent Speaker Program Fraud Cases,N.Y.U. J. Legis. & Pub. Pol’y Quorum(2021).

- 1Remuneration can include gifts as mundane as pens and pads of paper, food and beverage, “honoraria” payments (which are payments for certain kinds of consulting services), lodging, and expensive travel. See Charles Ornstein et al., We Found Over 700 Doctors Who Were Paid More Than a Million Dollars by Drug and Medical Device Companies, ProPublica (Oct. 17, 2019, 12:00 PM), https://www.propublica.org/article/we-found-over-700-doctors-who-were-paid-more-than-a-million-dollars-by-drug-and-medical-device-companies; Triangle et al., Types and Distributions of Payments From Industry to Physicians in 2015, JAMA. 2017 May 2;317(17):1774-1784 (May 2017), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28464140/.

- 2Puneet Manchanda & Elisabeth Honka,The Effects and Role of Direct-to-Physician Marketing in the Pharmaceutical Industry: An Integrative Review, 5 Yale J. Health Pol’y L. & Ethics 785 (2005), https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1127&context=yjhple; Susan F. Wood et al., Influence of Pharmaceutical Marketing on Medicare Prescriptions in the District of Columbia, PLOS ONE (Oct. 25, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186060; Elliot Morse et al., The Association Between Industry Payments and Brand-Name Prescriptions in Otolaryngologists, 161 J. Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery 605 (2019).

- 3Manvi Sharma et al., Association Between Industry Payments and Prescribing Costly Medications: An Observational Study Using Open Payments and Medicare Part D Data, BMC Health Servs. Res. (Apr. 2018), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324211217_Association_between_industry_payments_and_prescribing_costly_medications_An_observational_study_using_open_payments_and_medicare_part_D_data (to access, follow the “Download full-text PDF” hyperlink); Freek Fickweiler et al., Interactions Between Physicians and the Pharmaceutical Industry Generally and Sales Representatives Specifically and Their Association with Physicians’ Attitudes and Prescribing Habits: A Systematic Review, BMJ Open (Sept. 17, 2017), https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/7/9/e016408.full.pdf.

- 4Roy H. Perlis & Clifford S. Perlis, Physician Payments from Industry Are Associated with Greater Medicare Part D Prescribing Costs, PLOS ONE (May 16, 2016), https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155474.

- 5Edward C. Halperin et al., A Population-Based Study of the Prevalence and Influence of Gifts to Radiation Oncologists from Pharmaceutical Companies and Medical Equipment Manufacturers, 59 Int’l J. Radiation Oncology Biology Physics 1477 (2004), doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.01.052, PMID: 15275735.

- 6S. Madhavan et al., The Gift Relationship Between Pharmaceutical Companies and Physicians: An Exploratory Survey of Physicians, 22 J. Clinical Pharmacy & Therapeutics 207 (1997).

- 7See Orenstein et al., supra note 1.

- 8Id.

- 942 U.S.C. Code § 1320a-7h.

- 10The database can be searched here: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov.

- 11See, e.g., Teva Pharmaceuticals, Open Payments, https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/company/100000000141.

- 12This is a spreadsheet downloaded from Open Payments showing the expenditures made for Copaxone or Azilect by Teva Pharmaceuticals in 2014. The spreadsheet generated from Open Payments includes approximately 33 columns, many of which are irrelevant to the scope of this article (e.g. the date of the payment, the address of the receiving party, etc). If you are interested, you can download the full dataset from https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/company/100000000141.

- 13Adriane Fugh-Berman & Shahram Ahari, Following the Script: How Drug Reps Make Friends and Influence Doctors, PLOSMEDICINE (2007), https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.0040150&type=printable.

- 14Persuading the Prescribers: Pharmaceutical Industry Marketing and Its Influence on Physicians and Patients, The Pew Charitable Trusts (Nov. 11, 2013), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2013/11/11/persuading-the-prescribers-pharmaceutical-industry-marketing-and-its-influence-on-physicians-and-patients.

- 15Id.

- 16It is well-known that some pharmaceutical sales representatives fake their calls, see, e.g., Anonymous, How Many FAKE Calls You Make a Day?, Cafepharma: Daiichi-Sankyo (Mar. 19, 2014), http://www.cafepharma.com/boards/threads/how-many-fake-calls-you-make-a-day.553719/; Anonymous, Fake Calls – Enough Is Enough!!!!!!!!, Cafepharma: AstraZeneca (May. 12, 2012), http://www.cafepharma.com/boards/threads/fake-calls-enough-is-enough.501743/; Anonymous, HOW MANY FAKE CALLS DO YOU FAKE EACH DAY?, Cafepharma: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Apr. 3, 2011), http://www.cafepharma.com/boards/threads/how-many-calls-do-you-fake-each-day.462063/page-2.

- 17The Pew Charitable Trusts, supra note 14.

- 18Pharmaceutical companies have spent billions on “compensation for services other than consulting, including serving as faculty or as a speaker at a venue other than a continuing education program” for years 2017, 2018, and 2019 combined. Open Payments Complete 2017, 2018, and 2019 Program Year Datasets, CMS, https://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/Explore-the-Data/Data- Overview (accessed Sept. 9, 2020).

- 19See Plaintiff-Relators’ Mot. Opp’n Summ. J. at 21, Dkt. # 135, United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals 1:13-cv-0702 (CM), September 13, 2018.

- 20Jaclyn Jaeger, Teva to Pay $54M in FCA Whistleblower Settlement, Compliance Week (Jan. 7, 2020, 3:01 PM), https://www.complianceweek.com/whistleblowers/teva-to-pay-54m-in-fca-whistleblower-settlement/28281.article; Press Release, U.S. Att’y’s Off. S.D.N.Y., Acting Manhattan U.S. Attorney Announces $678 Million Settlement of Fraud Lawsuit Against Novartis Pharmaceuticals for Operating Sham Speaker Programs Through Which It Paid Over $100 Million to Doctors to Unlawfully Induce Them to Prescribe Novartis Drugs (July 1, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/acting-manhattan-us-attorney-announces-678-million-settlement-fraud-lawsuit-against.

- 21Press Release, Dep’t Just. Off. Pub. Affs., Justice Department Recovers Over $2.2 Billion from False Claims Act Cases in Fiscal Year 2020 (Jan. 14, 2021), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-recovers-over-22-billion-false-claims-act-cases-fiscal-year-2020.

- 22Order in Purcell v. Gilead, Dkt. # 282, 2:17-cv-03523 (MAK), July 28, 2021.

- 23See United States ex rel. Bilotta v. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Dkt. # 50 1:11-v-00071, July 10, 2013; United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Third Amended Complaint, Dkt. # 53, March 23, 2016; United States ex rel. Purcell et al. v. Gilead, Fourth Amended Complaint, Dkt. # 118, September 30, 2020.

- 24Government Mot. Opp’n Summ. J. at 11, Dkt. # 230, 1:11-cv-00071, August 29, 2018.

- 25Id. at 12.

- 26Id.

- 27The Government alleged that doctors would attend programs together and “take turns” speaking to each other, even though their audience was comprised of speakers who were trained to speak on the very same presentation they were hearing. Id. In their opposition to summary judgment, the Government noted one cluster that attended 34 programs together in a single year. Id.; see also Stipulation and Order of Dismissal, Dkt. # 342 at 11, 1:11-cv-00071, July 21, 2020 (Novartis admitted “[i]n thousands of instances, Novartis paid for the same group of doctors, often colleagues or friends, to have dinners together repeatedly (along with other doctors or health care providers on occasion). Doctors in these groups would sometimes rotate being the speaker and receiving the honorarium payment.”

- 28Code on Interactions with Health Care Professionals, PhRMA, https://www.phrma.org/-/media/Project/PhRMA/PhRMA-Org/PhRMA-Org/PDF/A-C/Code-of-Interaction_FINAL21.pdf (last visited Dec. 3, 2021).

- 29See Stipulation and Order of Dismissal, Dkt. # 342, 1:11-cv-00071, July 21, 2020.

- 30The data is likely understated as the Government noted “sales representatives often doctored the paperwork associated with these events to reduce the average per person cost reflected in the data,” Stipulation and Order of Dismissal, Dkt. # 342 at 11, 1:11-cv-00071, July 21, 2020. Novartis, like the Pharmaceutical Industry writ large, defines a “modest meal” as $125 per person for dinner. Under that definition, an individual can have $50 steak, a $50 bottle of wine, tip 20% and still fall below the threshold. See United States ex rel. Bilotta v. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Dkt. # 50 1:11-v-00071, July 10, 2013; United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Third Amended Complaint, Dkt. # 53, March 23, 2016; United States ex rel. Purcell et al. v. Gilead, Fourth Amended Complaint, Dkt. # 118, September 30, 2020; see also David F. Essi, “Mixing Dinner and Drugs – Is it Ethically Contraindicated?,” American Med. J. of Ethics, August 2015, Volume 17, Number 8: 787-795.

- 31Stipulation and Order of Dismissal, Dkt. # 342 at 7, 1:11-cv-00071, July 21, 2020.

- 32Government Mot. Opp’n Summ. J. at 5, Dkt. # 230, 1:11-cv-00071, August 29, 2018.

- 33Id. at 19.

- 34Id. at 2.

- 35Id. at 12.

- 36Stipulation and Order of Dismissal, Dkt. # 342 at 11, 1:11-cv-00071, July 21, 2020.

- 37Id. at 7.

- 38Id.

- 39Id.

- 40Novartis admitted “the ROI for doctors who attended more than one roundtable was 1,200%. Stipulation and Order of Dismissal, Dkt. # 342 at 8, 1:11-cv-00071, July 21, 2020.

- 41There is another case pending against Novartis Pharmaceuticals alleging substantially similar conduct regarding its Multiple Sclerosis drug, Gilenya. See United States ex rel. Camburn v. Novartis Pharmaceuticals, 1:13-cv-03700, Third Amended Complaint, Dkt. # 77, November 19, 2021.

- 42United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Third Amended Complaint, Dkt. # 53, March 23, 2016. This non-intervened case proceeded in the Southern District of New York and settled after Judge Colleen McMahon denied Teva’s Motion for Summary Judgment. It settled for $54 million. See Jaclyn Jaeger, “Teva to Pay $54 Million in FCA Whistleblower Settlement,” Compliance Week (Jan. 7, 2020), https://www.complianceweek.com/whistleblowers/teva-to-pay-54m-in-fca-whistleblower-settlement/28281.article.

- 43United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Memorandum of Law in Opposition to Summary Judgment, Dkt. # 135, September 13, 2018.

- 44United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Memorandum of Law in Opposition to Summary Judgment, Dkt. # 135, September 13, 2018.

- 45United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Plaintiffs-Relators’ Rule 56.1 Counterstatement, Dkt. # 136 at 87, 1:13-cv-03702 (CM), September 13, 2018.

- 46Id. at 68.

- 47Id.

- 48In 4 out of 30 audited programs, the independent monitor noted that the paid speaker left early. Id. at 69.

- 49Id. at 51.

- 50United States ex rel. Arnstein et al. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Memorandum of Law in Opposition to Summary Judgment, Dkt. # 135 at 22, September 13, 2018.

- 51This non-intervened suit did not include admissions like the Novartis case.

- 52See Transcript of Oral Argument Held on June 25, 2021 before Judge Honorable Mark A. Kearney, Dkt. # 273, 2:17-cv-03523 (MAK)and Order in Purcell v. Gilead, Dkt. # 282, 2:17-cv-03523 (MAK), July 28, 2021.

- 53United States ex rel. Purcell et al. v. Gilead, Fourth Amended Complaint, Dkt. # 118, September 30, 2020.

- 54Indeed, that is how the allegations were made in Novartis, Teva, and Gilead. That is, the reason prosecutors knew many events happened at Hooters was because Novartis collected venue information (as did Teva and Gilead).

- 55[3] NHE Fact Sheet, Ctrs. Medicare & Medicaid Servs., https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet (last updated Dec. 1, 2021).

- 56Even if legislative action proves futile, there is hope. Recently amended to the PhRMA Code have prompted some commentators to question whether Speaker Programs will be a thing of the past. See Ropes & Gray, PhRMA Code 2022: Speaker Programs Enter a Prohibition Era? (Sept. 20, 2021), https://www.ropesgray.com/en/newsroom/alerts/2021/September/PhRMA-Code-2022-Speaker-Programs-Enter-a-Prohibition-Era.