By: Mari Dugas

February 11, 2022

As the adage goes, cyber knows no borders or boundaries.1Michael Daniel, Tony Scott & Ed Felton, The President’s National Cybersecurity Plan: What You Need to Know, White House Blog (Feb. 9, 2016), https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2016/02/09/presidents-national-cybersecurity-plan-what-you-need-know; Christina Bergmann, There Are No Boundaries in Cyber Space, DW (Apr. 2, 2011), https://www.dw.com/en/there-are-no-boundaries-in-cyber-space/a-14817437; Fernando Heller, EU Digital Official: Cyber Threats Know No Borders, Euractiv (Sept. 26, 2017), https://www.euractiv.com/section/cybersecurity/interview/eu-digital-official-digital-threats-know-no-borders/. A catastrophic cyber incident against infrastructure physically located in one state of the United States can have spillover effects in another state, ramifications for the federal government, or both. The National Guard’s unique quasi-state and quasi-federal nature makes it an attractive option to both supplement the federal cybersecurity mission and promote active cyber defense at the state and local level.

The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) is the legislative mechanism for amending the federal statutes that control the authority of the National Guard, dictate when the National Guard may operate as an arm of the federal government, and fund the National Guard when in federal service, but the NDAA is also increasingly the primary means through which Congress passes cyber-related legislation.2Michael Garcia, The Militarization of Cyberspace? Cyber-Related Provisions in the National Defense Authorization Act, Third Way (Apr. 5, 2021), https://www.thirdway.org/memo/the-militarization-of-cyberspace-cyber-related-provisions-in-the-national-defense-authorization-act (noting in his review of the last five NDAAs, 2017-2021, that the NDAA “is now the primary vehicle to pass all matters of cybersecurity legislation”). Given more focus on cyber-related provisions in the NDAA, it is no surprise that recent NDAAs have expanded upon the National Guard’s role in cyberspace and opened a pathway to greater National Guard involvement in national cyber resiliency.3The National Governor’s Association (NGA) has identified the National Guard’s cyberspace operations as a priority for funding and support from Congress. The NGA argues that the National Guard could serve as an augmentation for addressing future cyber threats and incidents that state governments are ill-equipped to respond to. Letter Outlining Governors’ Legislative Priorities for the National Defense Authorization Act, Nat’l Governors Ass’n (Oct. 23, 2020), https://www.nga.org/advocacy-communications/letters-nga/letter-outlining-governors-legislative-priorities-for-the-national-defense-authorization-act/. The NDAA can only alter the circumstances under which the National Guard is authorized to operate in federal and quasi-federal status. But, given the National Guard’s duality and primary role at the state-level, changes in the NDAA ultimately influence state-level operations and capacity too. This article will explore the current authorities and structures that allow the National Guard to operate in cyberspace and examine the NDAA provisions that have expanded the National Guard’s role in cyberspace.

The National Guard’s Structure of Authorities

The National Guard is one of the oldest institutions in the United States and has a complex history as the standing militia of the fifty states. Only the Army and the Air Force have National Guard components. The Army National Guard was formalized by Congressional statute in 1792,4Federal Courts have articulated the history surrounding the National Guard’s founding. See e.g., Perpich v. Dep’t of Def., 496 U.S. 334, 340–47 (1990); Rendell v. Rumsfeld, 484 F.3d 236, 244 (3d Cir. 2007). but its “official birth date” is December 13, 1636, well before the Constitution and Declaration of Independence.5How We Began, Nat’l Guard, https://www.nationalguard.mil/about-the-guard/how-we-began/. The Air National Guard was born in 1947 when the U.S. Air Force itself became a distinct branch of the armed forces.6Id.

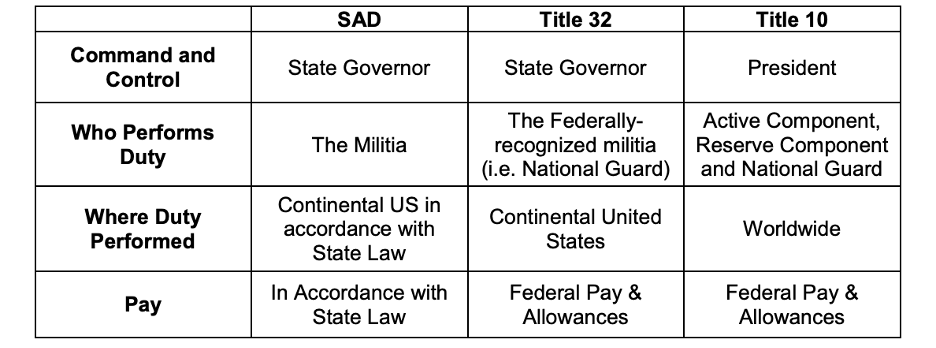

The National Guard is unique in that it can operate under three different legal statuses: State Active Duty (SAD), Title 32 authority, or Title 10 authority. The status of the National Guard dictates what the units can and cannot do, who facilitates training, who pays the units, and who takes on liability for the unit’s actions. The chart below offers a brief overview of the different operational statuses.7NGAUS Fact Sheet: Understanding the Guard’s Duty Status, Give an Hour (Sept. 27, 2018), http://giveanhour.org/wp-content/uploads/Guard-Status-9.27.18.pdf.

a) State Active Duty (SAD)

Under State Active Duty (SAD), the National Guard serves as an unambiguous instrument of state power, recalling its origin as a state militia force. Under SAD, the National Guard can be activated for a variety of state missions under the command and control of the governor. Traditional SAD duties include responding to local natural disasters, civil unrest, or health emergencies like COVID-19.8During the COVID-19 pandemic, National Guard units have been mobilized across the country to assist with emergency response and support. One article estimates that 15,600 National Guard troops are supporting the COVID-19 response, with more than 6,000 providing direct support to medical facilities. Zach Sheely, National Guard Helps Medical Facilities with COVID-19 Peak, Nat’l Guard, (Jan. 14, 2022), https://www.nationalguard.mil/News/Article/2900042/national-guard-helps-medical-facilities-with-covid-19-peak/. Governors may order the state National Guard to act in a law enforcement capacity,9NGAUS Fact Sheet – Guard Status, supra note 6. which arose as a political touchpoint after the National Guard was deployed in both state and federal capacities to respond to protests regarding the murder of George Floyd.10In response to nation-wide protests after the killing of an unarmed Black man, George Floyd, by police, President Donald Trump threatened state governors, stating that “he would dispatch the U.S. military to ‘quickly solve the problem for them’” if the governors did not deploy their own National Guard units in SAD status. Alana Wise, Trump Says He’ll Deploy Military to States if They Don’t Stop Violent Protests, NPR (June 1, 2020), https://www.npr.org/2020/06/01/867420472/trump-set-address-protests-against-police-killings-in-white-house-remarks. By June 2020, 24 states had already mobilized their National Guard units in SAD in response to protests across the country. Alexandra Sternlicht, Over 4,400 Arrests, 62,000 National Guard Troops Deployed: George Floyd Protests by the Numbers, Forbes (June 2, 2020), https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexandrasternlicht/2020/06/02/over-4400-arrests-62000-national-guard-troops-deployed-george-floyd-protests-by-the-numbers/?sh=2fa9aaed4fe1. SAD operations tend to be predicated on a declaration of an emergency by the governor (although such a state of emergency is not a mandatory prerequisite) and are supervised by the state National Guard’s Adjutant General (TAG).11 National Guard Fact Sheet Army National Guard (FY2005), Nat’l Guard Bureau 4 (May 3, 2006), https://www.nationalguard.mil/About-the-Guard/Army-National-Guard/Resources/News/ARNG-Media/FileId/137011/.

Individual states have their own statutes and regulations governing SAD. For example, Colorado’s Revised Statute 28-3-104 identifies the governor as the commander in chief and lays out some of the circumstances in which the National Guard can be deployed, such as law enforcement missions, defense of the state, or emergency response.12“The governor shall be the commander in chief of the military forces except so much thereof as may be in the actual service of the United States and may employ the same for the defense or relief of the state, the enforcement of its laws, the protection of life and property therein, and the implementation of the Emergency Management Assistance Compact; for service in a national special security event or in situations involving imminent danger of emergency or disaster; and for the training of the military forces for all appropriate state missions.” Colo. Rev. Stat. § 28-3-104 (2017). Similarly, Colorado’s Regulation 612, promulgated by the state’s Department of Military and Veteran Affairs lays out situations when the National Guard can be called up in SAD, including to protect life and property in the state and for federal training missions.13“[1] As commander in chief of the National Guard, the governor may order the National Guard to State Active Duty for the defense or relief of the state, the enforcement of its laws, and the protection of life and property in the state; [2] The governor may also order the National Guard to State Active Duty in anticipation of or in response to emergencies or disasters, to include the implementation of the Emergency Management Assistance Compact; [3] The governor may also call the National Guard to State Active Duty for their training for appropriate missions.” Regulation 612: Colorado National Guard State Active Duty Status, Dep’t Mil. & Veteran Aff. 1 (Sept. 1, 2010), https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/State%20Active%20Duty%20Regulation%20Handbook%201%20Oct%202010.pdf.

The Department of Defense Instruction (DODI) 3025.21 provides federal guidance on SAD, noting that the state National Guard “have primary responsibility to support State and local Government agencies for disaster responses and in domestic emergencies, including in response to civil disturbances; such activities would be directed by, and under the command and control of, the Governor, in accordance with State or territorial law and in accordance with Federal law.”14U.S. Dep’t of Def., Instr. 3025.21, Defense Support of Civilian Law Enforcement Agencies enclosure 4, para 4.b.

There have been recent efforts to understand how SAD operations may be utilized in cyberspace. The National Cyber Incident Response Plan (NCIRP) is one such example.15 The NCIRP was a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) document written during the Obama administration that offers guidance and institutional roles and responsibilities in the case of a national cyber incident. DHS is the executive branch agency responsible for homeland disaster and emergency planning and The Plan includes the National Guard as one of the entities that will be necessary in responding to a cyber incident. National Cyber Incident Response Plan, Dep’t Homeland Sec. (Dec. 2016), https://us-cert.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/ncirp/National_Cyber_Incident_Response_Plan.pdf. The NCIRP notes that the “National Guard may perform state missions, including supporting civil authorities in response to a cyber incident,” because National Guard members are assumed to have better understanding of state and local issues, and may have more technical expertise from private sector employment as IT or cybersecurity professionals.16Id. at 17. Since National Guard duty is not full time, National Guard members will have other careers, and in the context of cyberspace, may work for technology or cyber security companies and have strong technical backgrounds. See e.g., Monica M. Ruiz & David Forscey, The Hybrid Benefits of the National Guard, Lawfare (July 23, 2019, 8:00 AM), https://www.lawfareblog.com/hybrid-benefits-national-guard. Additionally, the NCIRP suggests that the National Guard can “perform federal service or be ordered to active duty to perform D[O]D missions, which could include supporting a federal agency in response to a cyber incident.”17Id.

Ransomware attacks provide clear precedent in favor of the deployment of the National Guard under SAD to provide cyber incident response. On March 30, 2018, Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper declared the first ever state of emergency in response to a cyber incident: Colorado’s Department of Transportation (CDOT), among other entities and state businesses, was victimized by the destructive SamSam ransomware.18SamSam is a type of ransomware that primarily targeted critical infrastructure sectors. Ransomware actors would gain access to victim computers and lock them until receiving a cryptocurrency payment. Alert (AA18-337A) SamSam Ransomware, Dep’t Homeland Sec. (Dec. 3, 2018), https://www.cisa.gov/uscert/ncas/alerts/AA18-337A. More than 2,000 CDOT computers were taken offline by the attack.19Tamara Chuang, How SamSam Ransomware Took Down CDOT and How the State Fought Back — Twice, Colo. Sun (Feb. 3, 2020), https://coloradosun.com/2020/02/03/how-samsam-ransomware-took-down-cdot-and-how-the-state-fought-back-twice/. CDOT officials refused to pay the ransom and instead spent two weeks getting their systems back online. The state struggled to contain the ransomware, get its computers back online, and make sure that the ransomware didn’t impact constituent-facing services such as traffic lights (which if taken offline, may have resulted in loss of life). By declaring a state of emergency, Governor Hickenlooper gained the authority to mobilize the National Guard and appropriate two million dollars to respond to the crisis, bringing “structure,” expertise, and relief to beleaguered Colorado officials.20Id.

In Louisiana, National Guard units were deployed in 2019 to help public schools open on time after they were targeted and temporarily taken offline by ransomware attacks.21 Terri Moon Cronk, National Guard Disrupts Cyberattacks Across U.S., Dep’t Def. (Nov. 7, 2019), https://www.defense.gov/Explore/News/Article/Article/2011827/national-guard-disrupts-cyberattacks-across-us/. Governor John Bel Edwards declared a state of emergency, freeing up resources and the authority to mobilize the state’s National Guard in a cyber incident response capacity.22State of La., Proclamation No. 115 JBE 2019, State of Emergency: Cybersecurity Incident (July 24, 2019), https://gov.louisiana.gov/assets/EmergencyProclamations/115-JBE-2019-State-of-Emergency-Cybersecurity-Incident.pdf; See also Benjamin Freed, Louisiana Declares Emergency Over Cyberattacks Targeting Schools, State Scoop (July 25, 2019), https://statescoop.com/louisiana-declares-emergency-over-cyberattacks-targeting-schools/. The National Guard members had “several goals. One [was] to try to find out where [the attack is] coming from, help salvage the IT systems that were impacted, and get things back up and running.”23Freed, supra note 22. The National Guard assisted in getting the victimized systems back online and initiating forensic investigations into the ransomware, which are both essential cyber incident response actions.

The National Guard has also been mobilized under SAD to help protect against and respond to cyber threats to elections. The impetus for this new role was evidence that Russian state sponsored hackers “probed information systems related to voter registration in 21 states, gaining access to at least two systems” in the leadup to the 2016 presidential election.24The State and Local Election Cybersecurity Playbook, Belfer Ctr. for Sci. & Int’l Affairs, Harv. Kennedy Sch.(Feb. 2018), https://www.belfercenter.org/index.php/publication/state-and-local-election-cybersecurity-playbook. Although there is no evidence that any information from voter registration databases was actively modified or destroyed, the fact that hackers had gained access to state election infrastructure drove several states to mobilize the National Guard to proactively search for adversaries on state networks ahead of the 2020 elections. In Colorado, the National Guard was tasked with “assist[ing] the Colorado Secretary of State’s Office and Office of Information Technology in network monitoring during the elections to prevent cyber-attacks and enhance integration across state agencies.”25 Colorado National Guard Teams Assist with Cyber Defense During Statewide Elections, Colo. Nat’l Guard Pub. Affairs (June 22, 2020), https://co.ng.mil/News/Archives/Article/2227488/colorado-national-guard-teams-assist-with-cyber-defense-during-statewide-electi/. In Delaware, the National Guard was authorized to hunt for threats to the state’s election infrastructure. The Illinois and Washington National Guard units were also authorized to assist state election officials with network defense.26Davis Winkie, Here’s How the National Guard Is Supporting the Nov. 3 Election, Military Times (Oct. 28, 2020), https://www.militarytimes.com/news/election-2020/2020/10/28/heres-how-the-national-guard-is-supporting-the-nov-3-election/.

b) Title 32

Title 32 status allocates the balance of authority over the National Guard between the state and federal government. Under Title 32 status, National Guard units are activated by their respective state governors with the approval of the President or Secretary of Defense. Title 32 operations must be predicated on a statutory authorization in Title 32 of the U.S. Code and are primarily used for training or homeland security purposes.27Homeland security is distinguishable from homeland defense, the former is under the Department of Homeland Security and the latter is generally governed by Title 10 of the U.S. Code and under DOD’s purview. Homeland defense is defined by Chapter 9 of Title 32 as “activit[ies] undertaken for the military protection of the territory or domestic population of the United States, or of infrastructure or other assets of the United States determined by the Secretary of Defense as being critical to national security, from a threat or aggression against the United States.” 32 U.S.C. § 901(1) (2007). The governor typically retains command and control of their respective National Guard unit in Title 32 status, but the operations are funded by DOD. Courts have confirmed that even when the National Guard is mobilized under Title 32 status, each state’s unit may serve local law enforcement duties as long as the state governor holds command and control.28Gilbert v. United States, 165 F.3d 470, 473 (6th Cir. 1999) (“The issue of status depends on command and control and not on whether . . . state or federal funds are being used…”); Stirling v. Brown, 227 Cal. Rptr. 3d 645, 651 (2018) (“When conducting domestic law enforcement support and mission assurance operations under the authorities of Title 32, National Guard members are under the command and control of the state and thus in a state status, but are paid with federal funds. Under Title 32, the Governor maintains command and control of National Guard forces even though those forces are being employed ‘in the service of the United States’ for a primarily federal purpose.”); Stirling v. Minasian, 955 F.3d 795, 799 (9th Cir. 2020) (“[M]embers of the National Guard only serve the federal military when they are formally called into the military service of the United States. At all other times, National Guard members serve solely as members of the State militia under the command of a state governor.”). Title 32 orders are capped at 30 days; after the 30-day period, federal benefits required under Title 10 status must be provided to the National Guard units.29Jim Absher, What’s the Difference Between Title 10 and Title 32 Mobilization Orders?, Military.com (Jan. 27, 2022), https://www.military.com/benefits/reserve-and-guard-benefits/whats-difference-between-title-10-and-title-32-mobilization-orders.html.

Title 32 provides statutory authorization for several distinct operations. For example, states can request funding for National Guard counterdrug missions under 32 U.S.C. § 112. Under this section, the National Guard is mobilized in a Title 32 status and funded federally for its counterdrug missions but remains under the command and control of the governor.3032 U.S.C. § 112. To mobilize counterdrug missions, the state must submit operational plans to DOD for approval.

Arguably the most ambiguous, and therefore permissive, authorization under Title 32 is Section 502(f)(2)(A), which allows members to participate in training and “[s]upport of operations or missions undertaken by the member’s unit at the request of the President or Secretary of Defense.”3132 U.S.C. § 502(f)(2)(A). Similarly, Section 503(a)(1) authorizes the National Guard to participate in “encampments, maneuvers, outdoor target practice, or other exercises for field or coast-defense instruction, independently of or in conjunction with the Army or the Air Force, or both.”32 32 U.S.C. § 503(a)(1). Participation in these types of operations can be compelled by the federal government “to prepare the National Guard for response to civil emergencies and disasters.”33Id.

Chapter 9 of Title 32 is one of the lesser-used statutory authorities, but it is especially relevant to cyberspace operations. Chapter 9 defines the National Guard’s limited “homeland defense” operations as “activity undertaken for the military protection of the territory or domestic population of the United States, or of infrastructure or other assets of the United States determined by the Secretary of Defense as being critical to national security, from a threat or aggression against the United States.”34 32 U.S.C. § 901(1) (2007). In general, Chapter 9 grants the Secretary of Defense wide latitude to define what constitutes an activity for the protection of infrastructure or other assets, which could offer particularly important flexibility to the National Guard’s operations in cyberspace under Title 32. Critically, Section 906 allows state governors to request funding for National Guard activities that fall within the umbrella of homeland defense. Since any major cyber incident could be reasonably defined as a threat to national security, and may have been by deemed so by DOD officials, governors may be able to mobilize the National Guard for cyberspace training or in response to cyber incidents with federal funding.35General Paul Nakasone, Commander of the United States Cyber Command and the Director of the National Security Agency, stated that “Even six months ago, we probably would have said, ‘Ransomware, that’s criminal activity’ . . . But if it has an impact on a nation, like we’ve seen, then it becomes a national security issue. If it’s a national security issue, then certainly [CYBERCOM is] going to surge toward it.” Nooman Merchant, General Promises US ‘Surge’ Against Foreign Cyberattacks, AP (Sept. 14, 2021), https://apnews.com/c4c8dace4708035d059be0fcd10e9e18. Likewise, Mieke Eoyang, Assistant Secretary of Defense (DASD) for Cyber Policy, also confirmed in her Congressional testimony that DOD “currently works to counter the ransomware threat as part of [its] mission to defend the nation in cyberspace.” Hearing to Receive Testimony on Recent Ransomware Attacks Before the Subcomm. on Cybersecurity of the S. Comm. on Armed Services, 117th Cong. 10 (2021) (statement of Mieke Eoyang, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Cyber Policy) https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/21-57_06-23-2021.pdf.

The DOD Domestic Operational Law Handbook has taken a relatively liberal view of Title 32 authorities, noting that the National Guard can be mobilized “to provide support to (1) active [duty military] component, (2) civil authorities, and (3) other statutorily eligible entities.”36Ctr. for Law and Military Operations, Domestic Operational Law Handbook for Judge Advocates 279 (2018), https://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/Military_Law/pdf/domestic-law-handbook-2018.pdf [hereinafter Domestic Law Handbook]. Supporting active components incidental to training is allowed so long as the primary purpose for mobilization was training. In practice, this may mean that the National Guard can be mobilized for a broad range of missions organized and funded by DOD, such as training for cyber incident response and emergency preparedness, so long as a training justification is provided. The Joint Chiefs of Staff memorandum on Defense Support of Civilian Authorities (DSCA) states that the National Guard in a Title 32 status can operate “in response to requests for assistance from civil authorities [whether state or federal] for domestic emergencies, law enforcement support, and other domestic activities, or from qualifying entities for special events.”37Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Pub. 3-28, Defense Support of Civil Authorities, at I-6 (2018).

Title 32 operations may fall under the Posse Comitatus Act (PCA), which prohibits the military from operating domestically and conducting law enforcement functions.38The PCA reads: “whoever, except in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress, willfully uses any part of the Army or the Air Force as a posse comitatus or otherwise to execute the laws shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than two years, or both.” The act effectively serves as a prohibition on the use of military force domestically unless in the case of a statutory exemption from Congress or an express Constitutional authorization. Title 10’s traditional military activities are generally subject to the PCA and thus, the federal military cannot operate domestically. 18 U.S.C. § 1385. See generally Jennifer K. Elsea, Cong. Research Serv., R42659, The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters: The Use of the Military to Execute Civilian Law (2018), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/R42659.pdf. While the PCA clearly applies to the National Guard in its federal Title 10 status, there are questions as to when it could apply to a Title 32 operation given the potential involvement of DOD and the President. Courts are split as to how far the PCA applies to the National Guard. In the Wounded Knee case, the United States District Court for the District of Nebraska construed the PCA as a bar on all military involvement in law enforcement, including the National Guard.39United States v. Jaramillo, 380 F. Supp. 1375 (D. Neb. 1974). In Red Feather, the United State District Court for the District of South Dakota conversely held that the PCA only barred military law enforcement when there was a risk of direct conflict with civilians.40United States v. Red Feather, 392 F. Supp. 916 (D.S.D. 1975). But, Courts have uniformly held that the PCA does not prohibit Section 112 counter-drug operations, despite their similarity to law enforcement duties, because the Guardsmen are conclusively not in federal service at the time.41Proving the National Guard is not in federal service is a statutory requirement for counterdrug operations’ approval. 32 U.S.C. § 112(c). See also Gilbert v. United States, 165 F.3d 470, 473–474 (6th Cir. 1999); Wallace v. State, 933 P.2d 1157, 1160 (Alaska Ct. App. 1997) (“Both the Third Circuit and a federal district court in Oregon have concluded that use of National Guard soldiers to enforce state criminal drug laws does not violate the Posse Comitatus Act.”). See generally Steven B. Rich, The National Guard, Drug Interdiction and Counterdrug Activities, and Posse Comitatus: The Meaning and Implications of “In Federal Service”, 1994 Army Law 35 (1994).

The Washington D.C. National Guard poses a unique complication to Title 32 operations. The mayor of D.C. does not control the D.C. Guard unit, rather, it always rests under federal control.42Elizabeth Goitein & Joseph Nunn, D.C.’s National Guard Should Be Controlled by Its Mayor, Not by a President Like Trump, Slate (Dec. 2, 2021, 3:56 PM), https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2021/12/defense-authorization-dc-national-guard-trump.html. The use of Section 502(f) by the President and Secretary of Defense to mobilize the D.C. Guard has raised questions about a federal “backdoor around the [PCA],” as articulated by Constitutional law scholar and professor Steve Vladeck in the aftermath of the mobilization of the National Guard to perform “law enforcement-like tasks” in Washington D.C. in the summer of 2020.43Steve Vladeck, Why Were Out-of-State National Guard Units in Washington, D.C.? The Justice Department’s Troubling Explanation, Lawfare (Jun. 9, 2020, 10:47 PM), https://www.lawfareblog.com/why-were-out-state-national-guard-units-washington-dc-justice-departments-troubling-explanation. Vladek argues that either Section 502(f) authorizes the President to call up any National Guard units to Washington D.C. at any point for any federal purpose, or the Guard units that were mobilized from eleven states were there illegally if Section 502(f) is read narrowly.44Id. In either case, Section 502(f) should be narrowed by Congress to address the ambiguities lest they are abused again in the future. Congress has debated amendments to Title 32 that would place more control of the National Guard in the mayor’s hands and reduce the President’s ability to use Title 32 to control the D.C. National Guard as a go-around of the PCA, but none have been successful thus far.45See, e.g., Norton Introduces Bill Requiring D.C. National Guard Commanding General to Live in D.C. (Apr. 1, 2021), https://norton.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/norton-introduces-bill-requiring-dc-national-guard-commanding-general-to. Congresswoman Norton (D-DC) previously introduced the District of Columbia National Guard Home Rule Act. H.R. 1090, 116th Cong. (2019–2020).

c) Title 10

Title 10 of the U.S. Code governs Traditional Military Activities (TMAs) which includes National Guard operations in a federal status, at the opposite end of the command-and-control continuum from SAD. The National Guard has a federal duty at all times, which is articulated by the Air National Guard as as maintaining “well-trained, well-equipped units available for prompt mobilization during war and provide assistance during national emergencies (such as natural disasters or civil disturbances).”46ANG Federal Mission, Air National Guard,https://www.ang.af.mil/About-Us/. Title 10 sets forth when the National Guard can be mobilized into federal service.

The primary provision for active-duty service and operations, 10 U.S.C. § 12304(b), states that military “Service Secretaries can call up reserve units, including the Guard, for 365 days or less without their consent, to active-duty service in support of preplanned operations for a Combatant Command.” In order for the Service Secretaries to call up the National Guard, or any other military units, they must have a legal authorization, pursuant to congressional authorization and presidential approval.47An example of a Congressional authorization is the 2002 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), which gives the President broad military powers to direct operations against al-Qaeda and successor forces. Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002, H.R.J. Res. 114, 107th Cong. § 3(a)(1) (2002) (enacted); 50 U.S.C. § 1541 (2018). Accordingly, Title 10 allows for the Guard to be deployed to an active theater of war.48 ANG Federal Mission, supra note 46. The National Guard can additionally be called up for duty in a Title 10 status in the case of a national emergency. Under Title 10, the National Guard is subject to the same regulations and rules as active-duty military troops, including the restrictions on law enforcement operations enshrined in the PCA.

In 2015, the Department of Defense (DOD) promulgated a manual on Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA) which was notable for its addition of cyber incidents to the list of circumstances under which the military may be involved in domestic responses, alongside natural disaster preparation and relief, and severe attacks on the homeland, nuclear or otherwise.49Air Land & Sea Application Ctr., Multi-Service Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Defense Support of Civilian Authorities (DSCA) (2021), https://fas.org/irp/doddir/army/atp3-28-1.pdf. The DSCA manual notes that, “[l]arge-scale cyber incidents may overwhelm government and private-sector resources by disrupting the internet and taxing critical infrastructure information systems. Complications from disruptions of this magnitude may threaten lives, property, the economy, and national security…. State and local networks operating in a disrupted or degraded environment may require DOD assistance.”50Id. at 74. When DOD assistance is required by states for any of the stated purposes, the National Guard can be federalized under Title 10 to perform these DOD DSCA missions. This manual provides that the National Guard “may be ordered or called into Federal service to ensure unified command and control of all Federal military forces for [cyber defense operations] when the President determines that action to be necessary in extreme circumstances.”51U.S. Dep’t of Def., Instr. 3025.21, Defense Support of Civilian Law Enforcement Agencies enclosure 4, para 4.b.

NDAA Cyber Provisions

The NDAA has served as a vehicle to introduce both cyber legislation and expand the operating scope of the National Guard under Title 10 and Title 32. Accordingly, the NDAA has opened the door to further National Guard involvement in cyber operations and defense and has promoted a more robust National Guard role in cyber resilience, even in SAD operations.

A notable NDAA innovation is the creation of a dual command status for Title 32 and Title 10 operations.5210 U.S.C. § 315; 32 U.S.C. §§ 315, 325 (2012 & Supp. IV 2017). The mobilized units operate under a dual status commander receiving orders from both the state and federal authorities, arguably allowing for more streamlined coordination between the state and federal governments during a crisis. In the cyberspace context, when incidents can span multiple states or implicate both state and federal equities, such flexibility is important. In these situations, the “Secretary of Defense must authorize the dual status, and the Governor of the effected State must consent.”5310 U.S.C. § 315; Domestic Law Handbook, supra note 36, at 25; 32 U.S.C. §§ 315, 325 (2012 & Supp. IV 2017). The dual status commander “could serve as an intermediate link between the separate chains of command for state and federal forces and is intended to promote unity of effort between federal and state forces to facilitate a rapid response during major disasters and emergencies.”54U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, GAO-16-332, DOD Needs to Clarify Its Roles and Responsibilities for Defense Support of Civil Authorities During Cyber Incidents 8 (2016), https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-16-332.pdf; see also LTG Laura Richardson, Commander, U.S. Army North, Conversation with Pallas Advisors (Apr. 7, 2021) (recognizing that when 29 states activated a dual status commander for their National Guard units involved in distributing vaccines it streamlined communication and coordination) (author’s notes). It is important to note though, that the commander does not command from a federal and state perspective simultaneously, rather they “command both federal and state forces in a mutually exclusive manner,” to avoid duplication of state and federal efforts in a crisis.55John T. Gereski, Jr., Two Hats Are Better Than One: The Dual-Status Commander in Domestic Operations, 2010 Army Law 72, 73 (2010).

The dual status command has been difficult to parse through in practice and there are not publicly available instances where a dual status command has been used to respond to a cyber incident. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) noted in a report that “in a recent cyber exercise there was a lack of unity of effort among the DOD and National Guard forces that were responding to the emergency but were not under the control of the dual status commander.”56GAO-16-332, supra note 53. In 2014, the Chief of the National Guard likewise expressed his desire for clarity about the role of dual status commanders, particularly with regards to cyberspace operations.57National Guard Bureau, Cyber Mission Analysis Assessment 9 (2014), https://info.publicintelligence.net/NG-CyberMissionAnalysis.pdf (submitted as required by the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2014). Given the especially fluid nature of cyber incidents that implicate both state and federal equities, a dual status command for a cyber incident could offer an attractive option to consolidate communication and response efforts.

Another push for innovative use of the National Guard in cyberspace operations came from the bipartisan Cyberspace Solarium Commission in 2020, which was created by Congress in the FY-2019 NDAA.58John McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 [NDAA FY-19], Pub. L. No. 115-232, 132 Stat. 1636 (2018). The Solarium report noted that “[s]tates have increasingly relied on National Guard units… to prepare for, respond to, and recover from cybersecurity incidents that overwhelm state and local assets.”59U.S. Cyberspace Solarium Commission, Cyberspace Solarium Commission Report, 65–66 (2020), https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ryMCIL_dZ30QyjFqFkkf10MxIXJGT4yv/view. The Solarium ultimately recommended that to best utilize the National Guard for cyber incident response, Congress needs to clarify National Guard duties and reimbursement policies particularly under Title 32, and better integrate the National Guard into military cyber incident response planning and training.60The Report also suggested that DOD clarify its internal policies on the same topics. Id. at 65. As a result of one of the Cyberspace Solarium’s recommendations, the FY-2021 NDAA “[d]irects the DoD to evaluate statutes, rules, regulations, and standards that pertain to the use of the National Guard for the response to and recovery from significant cyber incidents.”61The William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 [NDAA FY-21], H.R. 6395, 116th Cong., § 1729 (2020). See generally Senator Angus King, NDAA Enacts 25 Recommendations from the Bipartisan Cyberspace Solarium Commission (Jan. 2, 2021), https://www.king.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/ndaa-enacts-25-recommendations-from-the-bipartisan-cyberspace-solarium-commission (summarizing the Solarium recommendations that were ultimately included in the NDAA).

The NDAA FY-21 also suggests there is some ambiguity between 32 U.S.C. 502(f) and 32 U.S.C. 902 with respect to the National Guard’s authority to respond to cyber incidents. Congress required DOD to provide a review of regulations and the promulgation of guidance relating to National Guard responses to cyber incidents by Dec. 31, 2021. The report should “clarify when and under what conditions the participation of the National Guard in a response to a cyber attack qualifies as a homeland defense activity that would be compensated for by the Secretary of Defense under section 902 of such title.”62NDAA FY-21, supra note 61, § 1625(a)(1). This report, although not public at the time of this publication, should provide clarity on the parameters of the National Guard’s incident response authorities under Title 32.

The FY-2022 NDAA also introduced some cyber provisions, although many are written for DOD and not the National Guard specifically. For example, Section 1502 implements a pilot regional cybersecurity training center for the Army National Guard, highlighting a Congressional recognition for greater cyber training and resources in the National Guard.63 National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022 [NDAA FY-22], Pub. L. 117-81, 117th Cong., § 1502 (2021). Although the civilian membership National Guard has been seen as a presumptive source of cyber expertise, there are real constraints on manpower, talent retention, and budget that necessitate more robust cyber training within the National Guard. Section 1510 requires an assessment of the National Guard’s “capabilities to counter adversary use of ransomware, capabilities, and infrastructure.”64 Id., § 1510. Given the National Guard’s prior involvement in ransomware response at the state level,65See supra notes 18–28 and accompanying text. such an assessment should include to what extent and how the National Guard fits into the counter-ransomware surge. Section 1513 requires a report on potential DOD support and assistance for increasing the awareness of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) of cyber threats and vulnerabilities affecting critical infrastructure,66 NDAA FY-22, supra note 63, § 1513. which could also serve as a touchpoint for integrating the National Guard in domestic cyber incident response.

Other Legislation

Many other proposals related to the National Guard have wound their way through Congress but have not made it into the NDAA. Although these proposals are not law, they show Congress’s increasing appetite for understanding the National Guard’s role in cyberspace and willingness to support it accordingly. As recently as April 28, 2021, lawmakers introduced a bill that would create a joint DHS and DOD “Civilian Cybersecurity Reserve,” a National Guard-like corps that could serve as a surge force to response to cyber incidents.67 Civilian Cyber Security Reserve Act, S.1324, 117th Cong. (2021). However, this proposal from Sen. Jacky Rosen (D-NV) and Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) arguably just duplicates or even displaces existing National Guard capabilities. A stronger proposal would have instead focused on increasing state cyber capacity in the National Guard and committing more funding for specialized cyber units within the National Guard. The recently codified support for the National Guard cyber training facility in the FY-21 NDAA may lend itself towards this proposal by institutionalizing National Guard cyber expertise.

Other Congressional proposals have focused more directly on the National Guard’s cyber capacity, including the National Guard Cybersecurity Support Act, introduced by Senator Maggie Hassan (D-NH).68 NationalGuard Cyber Security Support Act, S.70, 117th Cong. (2021). The proposed legislation simply amends 32 U.S.C. 502(f)(1) to include “cybersecurity operations and missions to protect critical infrastructure.” However, this proposal, like the Rosen and Blackburn bill, doesn’t address the issue of constrained manpower and resources within the National Guard. While the authority of the National Guard to partake in such operations would be clearer, federal reimbursements for pay under this new bill would still be at the discretion of DOD. Representative Sheila Jackson (D-TX) introduced a similar bill to the 117th Congress. The bill would authorize a feasibility study on creating a “Cyber Defense National Guard,” although the bill does not make it clear if such a force would be under the purview of the National Guard, or more akin to the civilian corps proposed by Senators Rosen and Blackburn.

Each of these legislative proposals have their own logistical challenges and limitations. The reality remains that across the federal and state governments, cyber talent is hard to come by and retain, especially in consideration of governmental budgetary restraints that deny civil servants the flashy salaries and perks offered by the private sector. But in the context of defending against cyber threats, the National Guard is well situated to augment state incident response capacity, the military’s cyberspace operations, and the broader federal homeland security response to cyber incidents. Since National Guard troops only serve for limited periods of time, they can bring valuable expertise from their private sector jobs and may help close some of the talent gap that the federal government is grappling with in cybersecurity.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, Congress has not been as productive as it could be to capitalize on the National Guard’s nascent role in cyberspace, although there have been many positive developments in recent NDAAs. Cyber threats will continue to impact both the federal government and individual states; the National Guard is well positioned to be the critical connection between these sovereigns but the existing statutory authorizations for mobilization must be amended to clarify the scope of the National Guard’s role and provide adequate funding. The federal government and state authorities have overlapping interests in a more effective use of the Guard in domestic cyberspace, provided there can be clear legal guardrails by way of the NDAAs. In March 2021, General Paul N. Nakasone, Commander of the United States Cyber Command, stated at the Command’s annual legal conference that understanding how to utilize the Guard is an important problem for lawyers to tackle.69 Gen. Paul Nakasone, Commander, USCYBERCOM, U.S. Cyber Command Legal Conference (Mar. 4, 2021). Almost a year later, this is certainly still the case but the continued evolution of the National Guard’s role in cyberspace by legislators is a promising step forward. Changes to the law will be a key component of any future role the National Guard plays in responding to cyber threats. The current legal framework can only take us so far.

Mari Dugas, J.D. Class of 2022, New York University School of Law. Inaugural Student Volunteer at the United States Cyber Command Office of the Staff Judge Advocate. The views presented in this paper reflect the author’s alone and do not represent the views or policies of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Suggested Citation: Mari Dugas, Cyberspace Multiplier: Enhancing Domestic Cyberspace Resiliency with the National Guard, N.Y.U. J. Legis. & Pub. Pol’y Quorum (2022).

- 1Michael Daniel, Tony Scott & Ed Felton, The President’s National Cybersecurity Plan: What You Need to Know, White House Blog (Feb. 9, 2016), https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2016/02/09/presidents-national-cybersecurity-plan-what-you-need-know; Christina Bergmann, There Are No Boundaries in Cyber Space, DW (Apr. 2, 2011), https://www.dw.com/en/there-are-no-boundaries-in-cyber-space/a-14817437; Fernando Heller, EU Digital Official: Cyber Threats Know No Borders, Euractiv (Sept. 26, 2017), https://www.euractiv.com/section/cybersecurity/interview/eu-digital-official-digital-threats-know-no-borders/.

- 2Michael Garcia, The Militarization of Cyberspace? Cyber-Related Provisions in the National Defense Authorization Act, Third Way (Apr. 5, 2021), https://www.thirdway.org/memo/the-militarization-of-cyberspace-cyber-related-provisions-in-the-national-defense-authorization-act (noting in his review of the last five NDAAs, 2017-2021, that the NDAA “is now the primary vehicle to pass all matters of cybersecurity legislation”).

- 3The National Governor’s Association (NGA) has identified the National Guard’s cyberspace operations as a priority for funding and support from Congress. The NGA argues that the National Guard could serve as an augmentation for addressing future cyber threats and incidents that state governments are ill-equipped to respond to. Letter Outlining Governors’ Legislative Priorities for the National Defense Authorization Act, Nat’l Governors Ass’n (Oct. 23, 2020), https://www.nga.org/advocacy-communications/letters-nga/letter-outlining-governors-legislative-priorities-for-the-national-defense-authorization-act/.

- 4Federal Courts have articulated the history surrounding the National Guard’s founding. See e.g., Perpich v. Dep’t of Def., 496 U.S. 334, 340–47 (1990); Rendell v. Rumsfeld, 484 F.3d 236, 244 (3d Cir. 2007).

- 5How We Began, Nat’l Guard, https://www.nationalguard.mil/about-the-guard/how-we-began/.

- 6Id.

- 7NGAUS Fact Sheet: Understanding the Guard’s Duty Status, Give an Hour (Sept. 27, 2018), http://giveanhour.org/wp-content/uploads/Guard-Status-9.27.18.pdf.

- 8During the COVID-19 pandemic, National Guard units have been mobilized across the country to assist with emergency response and support. One article estimates that 15,600 National Guard troops are supporting the COVID-19 response, with more than 6,000 providing direct support to medical facilities. Zach Sheely, National Guard Helps Medical Facilities with COVID-19 Peak, Nat’l Guard, (Jan. 14, 2022), https://www.nationalguard.mil/News/Article/2900042/national-guard-helps-medical-facilities-with-covid-19-peak/.

- 9NGAUS Fact Sheet – Guard Status, supra note 6.

- 10In response to nation-wide protests after the killing of an unarmed Black man, George Floyd, by police, President Donald Trump threatened state governors, stating that “he would dispatch the U.S. military to ‘quickly solve the problem for them’” if the governors did not deploy their own National Guard units in SAD status. Alana Wise, Trump Says He’ll Deploy Military to States if They Don’t Stop Violent Protests, NPR (June 1, 2020), https://www.npr.org/2020/06/01/867420472/trump-set-address-protests-against-police-killings-in-white-house-remarks. By June 2020, 24 states had already mobilized their National Guard units in SAD in response to protests across the country. Alexandra Sternlicht, Over 4,400 Arrests, 62,000 National Guard Troops Deployed: George Floyd Protests by the Numbers, Forbes (June 2, 2020), https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexandrasternlicht/2020/06/02/over-4400-arrests-62000-national-guard-troops-deployed-george-floyd-protests-by-the-numbers/?sh=2fa9aaed4fe1.

- 11National Guard Fact Sheet Army National Guard (FY2005), Nat’l Guard Bureau 4 (May 3, 2006), https://www.nationalguard.mil/About-the-Guard/Army-National-Guard/Resources/News/ARNG-Media/FileId/137011/.

- 12“The governor shall be the commander in chief of the military forces except so much thereof as may be in the actual service of the United States and may employ the same for the defense or relief of the state, the enforcement of its laws, the protection of life and property therein, and the implementation of the Emergency Management Assistance Compact; for service in a national special security event or in situations involving imminent danger of emergency or disaster; and for the training of the military forces for all appropriate state missions.” Colo. Rev. Stat. § 28-3-104 (2017).

- 13“[1] As commander in chief of the National Guard, the governor may order the National Guard to State Active Duty for the defense or relief of the state, the enforcement of its laws, and the protection of life and property in the state; [2] The governor may also order the National Guard to State Active Duty in anticipation of or in response to emergencies or disasters, to include the implementation of the Emergency Management Assistance Compact; [3] The governor may also call the National Guard to State Active Duty for their training for appropriate missions.” Regulation 612: Colorado National Guard State Active Duty Status, Dep’t Mil. & Veteran Aff. 1 (Sept. 1, 2010), https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/State%20Active%20Duty%20Regulation%20Handbook%201%20Oct%202010.pdf.

- 14U.S. Dep’t of Def., Instr. 3025.21, Defense Support of Civilian Law Enforcement Agencies enclosure 4, para 4.b.

- 15The NCIRP was a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) document written during the Obama administration that offers guidance and institutional roles and responsibilities in the case of a national cyber incident. DHS is the executive branch agency responsible for homeland disaster and emergency planning and The Plan includes the National Guard as one of the entities that will be necessary in responding to a cyber incident. National Cyber Incident Response Plan, Dep’t Homeland Sec. (Dec. 2016), https://us-cert.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/ncirp/National_Cyber_Incident_Response_Plan.pdf.

- 16Id. at 17. Since National Guard duty is not full time, National Guard members will have other careers, and in the context of cyberspace, may work for technology or cyber security companies and have strong technical backgrounds. See e.g., Monica M. Ruiz & David Forscey, The Hybrid Benefits of the National Guard, Lawfare (July 23, 2019, 8:00 AM), https://www.lawfareblog.com/hybrid-benefits-national-guard.

- 17Id.

- 18SamSam is a type of ransomware that primarily targeted critical infrastructure sectors. Ransomware actors would gain access to victim computers and lock them until receiving a cryptocurrency payment. Alert (AA18-337A) SamSam Ransomware, Dep’t Homeland Sec. (Dec. 3, 2018), https://www.cisa.gov/uscert/ncas/alerts/AA18-337A.

- 19Tamara Chuang, How SamSam Ransomware Took Down CDOT and How the State Fought Back — Twice, Colo. Sun (Feb. 3, 2020), https://coloradosun.com/2020/02/03/how-samsam-ransomware-took-down-cdot-and-how-the-state-fought-back-twice/.

- 20Id.

- 21Terri Moon Cronk, National Guard Disrupts Cyberattacks Across U.S., Dep’t Def. (Nov. 7, 2019), https://www.defense.gov/Explore/News/Article/Article/2011827/national-guard-disrupts-cyberattacks-across-us/.

- 22State of La., Proclamation No. 115 JBE 2019, State of Emergency: Cybersecurity Incident (July 24, 2019), https://gov.louisiana.gov/assets/EmergencyProclamations/115-JBE-2019-State-of-Emergency-Cybersecurity-Incident.pdf; See also Benjamin Freed, Louisiana Declares Emergency Over Cyberattacks Targeting Schools, State Scoop (July 25, 2019), https://statescoop.com/louisiana-declares-emergency-over-cyberattacks-targeting-schools/.

- 23Freed, supra note 22.

- 24The State and Local Election Cybersecurity Playbook, Belfer Ctr. for Sci. & Int’l Affairs, Harv. Kennedy Sch.(Feb. 2018), https://www.belfercenter.org/index.php/publication/state-and-local-election-cybersecurity-playbook.

- 25Colorado National Guard Teams Assist with Cyber Defense During Statewide Elections, Colo. Nat’l Guard Pub. Affairs (June 22, 2020), https://co.ng.mil/News/Archives/Article/2227488/colorado-national-guard-teams-assist-with-cyber-defense-during-statewide-electi/.

- 26Davis Winkie, Here’s How the National Guard Is Supporting the Nov. 3 Election, Military Times (Oct. 28, 2020), https://www.militarytimes.com/news/election-2020/2020/10/28/heres-how-the-national-guard-is-supporting-the-nov-3-election/.

- 27Homeland security is distinguishable from homeland defense, the former is under the Department of Homeland Security and the latter is generally governed by Title 10 of the U.S. Code and under DOD’s purview. Homeland defense is defined by Chapter 9 of Title 32 as “activit[ies] undertaken for the military protection of the territory or domestic population of the United States, or of infrastructure or other assets of the United States determined by the Secretary of Defense as being critical to national security, from a threat or aggression against the United States.” 32 U.S.C. § 901(1) (2007).

- 28Gilbert v. United States, 165 F.3d 470, 473 (6th Cir. 1999) (“The issue of status depends on command and control and not on whether . . . state or federal funds are being used…”); Stirling v. Brown, 227 Cal. Rptr. 3d 645, 651 (2018) (“When conducting domestic law enforcement support and mission assurance operations under the authorities of Title 32, National Guard members are under the command and control of the state and thus in a state status, but are paid with federal funds. Under Title 32, the Governor maintains command and control of National Guard forces even though those forces are being employed ‘in the service of the United States’ for a primarily federal purpose.”); Stirling v. Minasian, 955 F.3d 795, 799 (9th Cir. 2020) (“[M]embers of the National Guard only serve the federal military when they are formally called into the military service of the United States. At all other times, National Guard members serve solely as members of the State militia under the command of a state governor.”).

- 29Jim Absher, What’s the Difference Between Title 10 and Title 32 Mobilization Orders?, Military.com (Jan. 27, 2022), https://www.military.com/benefits/reserve-and-guard-benefits/whats-difference-between-title-10-and-title-32-mobilization-orders.html.

- 3032 U.S.C. § 112.

- 3132 U.S.C. § 502(f)(2)(A).

- 3232 U.S.C. § 503(a)(1).

- 33Id.

- 3432 U.S.C. § 901(1) (2007).

- 35General Paul Nakasone, Commander of the United States Cyber Command and the Director of the National Security Agency, stated that “Even six months ago, we probably would have said, ‘Ransomware, that’s criminal activity’ . . . But if it has an impact on a nation, like we’ve seen, then it becomes a national security issue. If it’s a national security issue, then certainly [CYBERCOM is] going to surge toward it.” Nooman Merchant, General Promises US ‘Surge’ Against Foreign Cyberattacks, AP (Sept. 14, 2021), https://apnews.com/c4c8dace4708035d059be0fcd10e9e18. Likewise, Mieke Eoyang, Assistant Secretary of Defense (DASD) for Cyber Policy, also confirmed in her Congressional testimony that DOD “currently works to counter the ransomware threat as part of [its] mission to defend the nation in cyberspace.” Hearing to Receive Testimony on Recent Ransomware Attacks Before the Subcomm. on Cybersecurity of the S. Comm. on Armed Services, 117th Cong. 10 (2021) (statement of Mieke Eoyang, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Cyber Policy) https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/21-57_06-23-2021.pdf.

- 36Ctr. for Law and Military Operations, Domestic Operational Law Handbook for Judge Advocates 279 (2018), https://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/Military_Law/pdf/domestic-law-handbook-2018.pdf [hereinafter Domestic Law Handbook].

- 37Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Pub. 3-28, Defense Support of Civil Authorities, at I-6 (2018).

- 38The PCA reads: “whoever, except in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress, willfully uses any part of the Army or the Air Force as a posse comitatus or otherwise to execute the laws shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than two years, or both.” The act effectively serves as a prohibition on the use of military force domestically unless in the case of a statutory exemption from Congress or an express Constitutional authorization. Title 10’s traditional military activities are generally subject to the PCA and thus, the federal military cannot operate domestically. 18 U.S.C. § 1385. See generally Jennifer K. Elsea, Cong. Research Serv., R42659, The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters: The Use of the Military to Execute Civilian Law (2018), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/R42659.pdf.

- 39United States v. Jaramillo, 380 F. Supp. 1375 (D. Neb. 1974).

- 40United States v. Red Feather, 392 F. Supp. 916 (D.S.D. 1975).

- 41Proving the National Guard is not in federal service is a statutory requirement for counterdrug operations’ approval. 32 U.S.C. § 112(c). See also Gilbert v. United States, 165 F.3d 470, 473–474 (6th Cir. 1999); Wallace v. State, 933 P.2d 1157, 1160 (Alaska Ct. App. 1997) (“Both the Third Circuit and a federal district court in Oregon have concluded that use of National Guard soldiers to enforce state criminal drug laws does not violate the Posse Comitatus Act.”). See generally Steven B. Rich, The National Guard, Drug Interdiction and Counterdrug Activities, and Posse Comitatus: The Meaning and Implications of “In Federal Service”, 1994 Army Law 35 (1994).

- 42Elizabeth Goitein & Joseph Nunn, D.C.’s National Guard Should Be Controlled by Its Mayor, Not by a President Like Trump, Slate (Dec. 2, 2021, 3:56 PM), https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2021/12/defense-authorization-dc-national-guard-trump.html.

- 43Steve Vladeck, Why Were Out-of-State National Guard Units in Washington, D.C.? The Justice Department’s Troubling Explanation, Lawfare (Jun. 9, 2020, 10:47 PM), https://www.lawfareblog.com/why-were-out-state-national-guard-units-washington-dc-justice-departments-troubling-explanation.

- 44Id.

- 45See, e.g., Norton Introduces Bill Requiring D.C. National Guard Commanding General to Live in D.C. (Apr. 1, 2021), https://norton.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/norton-introduces-bill-requiring-dc-national-guard-commanding-general-to. Congresswoman Norton (D-DC) previously introduced the District of Columbia National Guard Home Rule Act. H.R. 1090, 116th Cong. (2019–2020).

- 46ANG Federal Mission, Air National Guard,https://www.ang.af.mil/About-Us/.

- 47An example of a Congressional authorization is the 2002 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), which gives the President broad military powers to direct operations against al-Qaeda and successor forces. Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002, H.R.J. Res. 114, 107th Cong. § 3(a)(1) (2002) (enacted); 50 U.S.C. § 1541 (2018).

- 48ANG Federal Mission, supra note 46.

- 49Air Land & Sea Application Ctr., Multi-Service Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Defense Support of Civilian Authorities (DSCA) (2021), https://fas.org/irp/doddir/army/atp3-28-1.pdf.

- 50Id. at 74.

- 51U.S. Dep’t of Def., Instr. 3025.21, Defense Support of Civilian Law Enforcement Agencies enclosure 4, para 4.b.

- 5210 U.S.C. § 315; 32 U.S.C. §§ 315, 325 (2012 & Supp. IV 2017).

- 5310 U.S.C. § 315; Domestic Law Handbook, supra note 36, at 25; 32 U.S.C. §§ 315, 325 (2012 & Supp. IV 2017).

- 54U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, GAO-16-332, DOD Needs to Clarify Its Roles and Responsibilities for Defense Support of Civil Authorities During Cyber Incidents 8 (2016), https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-16-332.pdf; see also LTG Laura Richardson, Commander, U.S. Army North, Conversation with Pallas Advisors (Apr. 7, 2021) (recognizing that when 29 states activated a dual status commander for their National Guard units involved in distributing vaccines it streamlined communication and coordination) (author’s notes).

- 55John T. Gereski, Jr., Two Hats Are Better Than One: The Dual-Status Commander in Domestic Operations, 2010 Army Law 72, 73 (2010).

- 56GAO-16-332, supra note 53.

- 57National Guard Bureau, Cyber Mission Analysis Assessment 9 (2014), https://info.publicintelligence.net/NG-CyberMissionAnalysis.pdf (submitted as required by the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2014).

- 58John McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 [NDAA FY-19], Pub. L. No. 115-232, 132 Stat. 1636 (2018).

- 59U.S. Cyberspace Solarium Commission, Cyberspace Solarium Commission Report, 65–66 (2020), https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ryMCIL_dZ30QyjFqFkkf10MxIXJGT4yv/view.

- 60The Report also suggested that DOD clarify its internal policies on the same topics. Id. at 65.

- 61The William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 [NDAA FY-21], H.R. 6395, 116th Cong., § 1729 (2020). See generally Senator Angus King, NDAA Enacts 25 Recommendations from the Bipartisan Cyberspace Solarium Commission (Jan. 2, 2021), https://www.king.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/ndaa-enacts-25-recommendations-from-the-bipartisan-cyberspace-solarium-commission (summarizing the Solarium recommendations that were ultimately included in the NDAA).

- 62NDAA FY-21, supra note 61, § 1625(a)(1).

- 63National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022 [NDAA FY-22], Pub. L. 117-81, 117th Cong., § 1502 (2021).

- 64Id., § 1510.

- 65See supra notes 18–28 and accompanying text.

- 66NDAA FY-22, supra note 63, § 1513.

- 67Civilian Cyber Security Reserve Act, S.1324, 117th Cong. (2021).

- 68NationalGuard Cyber Security Support Act, S.70, 117th Cong. (2021).

- 69Gen. Paul Nakasone, Commander, USCYBERCOM, U.S. Cyber Command Legal Conference (Mar. 4, 2021).