How the Hidden Costs of FOIA and Open Records Laws Impact the Public’s Ability to Request Government Documents

By: Kelly Cox1Kelly Cox is a graduate of the University of Miami School of Law, Class of 2016. She is the General Counsel at Miami Waterkeeper & Adjunct Faculty Member at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science. Kelly is deeply grateful to her co-author Matthew Haber, Daniel Parobok, Susie Cox, Jim Porter, Brett Brumund, and the staff of Miami Waterkeeper for their support in developing this paper. She also wishes to thank the editorial board and staff of this law review for their work. & Matthew Haber2 Matthew Haber is a graduate of Duke University School of Law, Class of 2013, whose practice focuses on local government and administrative law. He helped build the City of Miami’s first Public Records Division and oversaw training for all of the city’s employees on fulfilling citizen requests for public records. Matthew is deeply grateful to his co-author Kelly Cox, Joseph Pulido, Jihan Soliman, Xavier Alban, Professor Dan Smith, and the public records custodians at Baton Rouge, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, and Los Angeles for making themselves available for interviews. He would also like to thank the officials at Cape Coral, Ft. Lauderdale, Miami, Orlando, and Tallahassee for providing their public records request logs.3[1] Both authors would like to thank our University of Florida research team for countless hours of public records review and attention to detail: Amanda J. Acevedo, Tara S. Garner, and Marcos J. Izquierdo. Thanks are also due to Jessica Dennis, Casey Dresbach, Nicole Sedran, and Meagan Collins for their research and mapping assistance.

December 15, 2020

Abstract:

Should the public be required to pay to access government records? This Article takes a broad look at public records fees across the United States, using Florida as a case study throughout. Under Florida law, governments may recover a reasonable fee in exchange for producing government documents. These fees can block access for individuals and organizations without the ability to pay. As we demonstrate, adding a public-interest fee-waiver provision would remove financial barriers to accessing records without burdening government agencies. Modeled after the fee waiver provisions in the federal Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”), we propose that state and local governments implement policies for reviewing records requests and granting waivers to entities and individuals pursuing documents in the public interest. As part of this study, we reviewed thousands of public records requests across five major cities in Florida to determine what percentage of requesters might actually qualify for a public-interest fee waiver.

I. Introduction

A. Public Records Fees

There is a longstanding expectation in the United States that government information is public property subject to inspection and review. With that in mind, should the public be required to pay to access government records?

This Article takes a broad look at public records fees in the United States, using Florida as a case study throughout. Across the country, individual state laws — including Florida’s Public Records Act — permit governments to recover reasonable fees in exchange for public documents. These fees can block access for individuals and organizations, favoring access for those entities with the capacity to pay.

In principle, a fee waiver policy would remove that obstacle by eliminating or reducing the fees associated with certain categories of public records requests. The Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) — the federal government’s public records law — contains such a fee waiver provision for entities acting in the public interest. FOIA was enacted in 1966 “in response to a persistent problem . . . of obtaining adequate information to evaluate federal programs and formulate wise policies.”4Soucie v. David, 448 F.2d 1067, 1080 (D.C. Cir. 1971). In adopting FOIA, Congress granted the public access to crucial information and bolstered concerned citizens’ ability to hold governmental institutions accountable.5Prior to the enactment of FOIA, many states already had regulations on the books pertaining to public records. Florida was an early adopter, enacting its first public records law in 1909. See Office of the Attorney General of Florida, Open Government — The “Sunshine” Law, available at https://myfloridalegal.com/pages.nsf/Main/DC0B20B7DC22B7418525791B006A54E4#:~:text=Florida%20began%20its%20tradition%20of,unless%20specifically%20exempted%20by%20the. Other states also enacted open records laws before FOIA: Louisiana lawmakers enacted the Public Records Act in 1940, New Mexico’s Open Records Law was enacted in 1947, Pennsylvania’s Right to Know Act was originally adopted in 1957, and Maine’s Freedom of Access Act was enacted in 1959. Sophie Winkler, Nat’l Ass’n of Counties, Open Records Laws: A State by State Report (2010), https://www.governmentecmsolutions.com/files/124482256.

This Article explores the practical application of fee waivers and recommends data-driven changes to align records policies more closely with the public’s interest in transparent and accountable government. Specifically, this Article discusses: (1) public records laws across the United States; (2) proposed criteria for fee waiver policies; (3) an analysis of public records requests across five Florida cities to determine what percentage of requesters might actually qualify for a public-interest fee waiver; and (4) the likely impacts of fee waiver policies. The results of this preliminary research suggest that, if a fee waiver provision were adopted into Florida’s public records law, it would not burden government records custodians.

B. Fees Obstruct the Public’s Access to Information

Before the adoption of FOIA’s fee waiver provision, early analyses of the law suggested that it primarily benefited commercial enterprises because high fees prevented most non-profit organizations, news media, and academic researchers from requesting government documents.6John Bonine, Public-Interest Fee Waivers Under the Freedom of Information Act, 1980 Duke L. Rev. 213, 214-15 (1981), https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2768&context=dlj. To remove this obstacle, Congress amended FOIA in 1974 to create a “fee waiver” provision.7Id. at 215 n.7. Even after the addition of a fee waiver provision, only 2% of all FOIA requests alleged a “benefit to the general public” that might qualify for a fee waiver.8Id. at 216; see generally United States Department of Justice, Create a FOIA Report, available at https://www.foia.gov/data.html (last accessed Dec. 14, 2020).

For the same reasons that FOIA’s fees initially hindered access to federal records, fees written into state public records laws and local ordinances can reduce government transparency and accountability, or even prevent access to government documents altogether.

Public records fees are an especially difficult hurdle for 501(c)(3) non-profit organizations. Non-profits are typically supported by donations, grants, and other funding that comes with restrictions. As a result, many non-profit budgets are dominated by funds that can only be spent on specific projects or programs, leaving a much smaller amount allocated to overhead.9See Jennifer Casacchia, 7 Things Every Nonprofit Should Know About Restricted Assets, American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Blog (Mar. 30, 2018), https://blog.aicpa.org/2018/03/7-things-every-nonprofit-should-know-about-restricted-assets.html; Greg McRay, Are You Misappropriating Your Nonprofit’s Funds?, Foundation Group (Mar. 23, 2017), https://www.501c3.org/misappropriating-nonprofit-funds/. If a non-profit organization needs government records to further its public purpose, fees associated with the records request can prevent it from accessing that information when discretionary funds are not available. In the case of Miami Waterkeeper,10See generally Miami Waterkeeper, www.miamiwaterkeeper.org. an environmentally focused non-profit organization, discretionary spending accounts for less than 10% of the yearly operating budget on average. Of the remaining 90% in the budget, approximately 80% of expenses are bound by restricted funds with 10% allocated to general operating expenses. Not all non-profit organizations maintain identical budget structures, but this example demonstrates that non-profit organizations may have little flexibility in discretionary spending.

To further illustrate the rigid nature of a non-profit budget, consider the following incident. In 2017, a member of the public warned Miami Waterkeeper about a potential leak in a sewage outfall pipe buried beneath Biscayne Bay. The report, which indicated that the sewage leak was occurring much closer to shore than legally permitted, was later confirmed by Miami Waterkeeper’s dive team. To determine whether or not the county was aware of the leak, Miami Waterkeeper requested information, under Florida’s public records law, from the county’s Water and Sewer Department. In response to this records request, the county issued an invoice for more than $750.11Invoice on file with the authors. The data requested was pre-existing in digital format, and no printing or copying was necessary in order to respond to this request. Additional legal review of these documents would have likely increased the cost of this request. Such a high fee is statutorily permitted under Florida’s public records law, but it is also much more than the average citizen can afford. The request ended up costing 2% of Miami Waterkeeper’s discretionary budget for the year.12Request on file with authors.

Under this fee structure, Miami Waterkeeper could only request digital records of this size a limited number of times per year.13See Miami Waterkeeper annual budget on file with authors. In 2017, 11% of MWK’s operating budget was discretionary. In 2017, 2% was discretionary. In 2018, 3% was discretionary. In 2019, 1% was discretionary. In 2020, 9% is discretionary. Although Miami Waterkeeper has a discretionary budget at its disposal, not all organizations or individuals do. Fees this high are not uncommon, which creates an imbalance as to who is actually entitled to view public information.14See invoices on file with authors. Without public-interest fee waivers, the public records request process can become a “pay-to-play” environment where only those entities or individuals who can pay for public access to information are afforded access to it.

C. Why Public Access to Information Matters

Forty years ago, the United States Supreme Court concluded that the “basic purpose of [public records laws] is to ensure an informed citizenry, vital to the functioning of a democratic society, needed to check against corruption and to hold the governors accountable to the governed.”15N.L.R.B. v. Robbins Tire & Rubber Co., 437 U.S. 214, 242 (1978). Beyond rhetoric, these democratic principles have real-world implications across all levels of government. Public records laws “allow individuals to request public documents from governments without need to demonstrate interest or standing, and require officials to respond, subject to certain legal exemptions.”16Daniel Berliner, Alex Ingrams & Suzanne J. Piotrowski, The Future of FOIA in an Open Government World: Implications of the Open Government Agenda for Freedom of Information Policy and Implementation, 63 Vil. L. Rev. 867, 869 (2019).

Consider the sewage leak example in the previous section. The records, as it turned out, contained emails between county officials undeniably showing that departmental leadership had been aware of the leak and failed to take action to repair the pipe for more than a year. As a result of this failure to respond promptly to a known leak, the pipe spewed approximately ten million gallons of partially treated sewage into the ocean less than one mile from a popular beach. Consequently, Miami Waterkeeper filed a 60-day Notice of Intent to Sue the county under the Clean Water Act. Within three days of filing this action, the county had plugged the leaking pipe. Without the ability to pay the records fee, Miami Waterkeeper would likely not have filed the notice letter, repair of the pipe may have never been prioritized, and public and environmental health could have remained compromised.17See, e.g., Indiana Department of Health, Diseases Involving Sewage (last visited Nov. 8, 2020), https://www.in.gov/isdh/22963.htm. Ultimately, the county charged a total fee of $450.71 for the digital records (which were primarily emails). This amount, although reduced, was still almost 1.4% of Miami Waterkeeper’s discretionary budget. Invoices on file with authors.

The importance of public records in holding governments accountable extends beyond the state of Florida. A federal judge recently ordered the Small Business Administration to publish detailed data about the businesses chosen to receive loans under the CARES Act Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) enacted in response to the coronavirus pandemic.18See Ben Popken & Andrew W. Lehren, Judge Orders Trump Administration to Reveal PPP Loan Data It Sought to Obscure, NBC News (Nov. 6, 2020), https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/judge-orders-trump-administration-reveal-ppp-loan-data-it-sought-n1246792. The order revealed troubling information about potential mismanagement of loan disbursements – information that would have remained secret without public access to government records.19See Ben Popken & Andrew W. Lehren, Release of PPP Loan Recipients’ Data Reveals Troubling Patterns, NBC News (Dec. 2, 2020), https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/release-ppp-loan-recipients-data-reveals-troubling-patterns-n1249629 (explaining that tenants of President Trump and his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, may have benefitted disproportionately from loan disbursements that, in turn, went to pay rent owed to them).

The water crisis in Flint, Michigan also demonstrates what can happen when members of the public do not become aware of a problem in time to protect themselves. In April 2014, Flint city officials changed the drinking water source for the city to the contaminated Flint River as a temporary cost-saving measure, causing harm and illness for hundreds of thousands of residents.20Contamination from the Flint River harmed more than 100,000 residents, causing an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease, among other illnesses. See Anya Smith et al., Multiple Sources of the Outbreak of Legionnaires’ Diseases in Genesee County, Michigan, in 2014 and 2015, 127 Envtl. Health Persp., (2019), available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6957290. Once made public, government records revealed that local officials had been aware of the health risks of the contaminated river but failed to act.21Ron Fonger, Expert Says TTHM Levels in Flint Water Were Immediate Evidence of Trouble Ahead, MLive, (last updated Jan. 30. 2019), https://www.mlive.com/news/flint/2018/08/expert_says_initial_tests_were.html; Jonathan Oosting, Jim Lynch & Chad Livengood, ‘Disaster’ Warning Preceded Flint Water Switch, Detroit News, (Mar. 10, 2016), https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/politics/2016/03/10/disaster-warning-preceded-flint-water-switch/81629048/; Oona Goodin-Smith, State Health Chief Gave Different Timelines of Flint’s Legionella Outbreak, MLive, (last updated Jan. 19, 2019). But public records can be used to prevent crises too. For example, a team of researchers in North Carolina attempted to use public records proactively to determine whether municipal waste disposal practices were affecting human health.22See Alexander Keil, Steven Wing & Amy Lowman, Suitability of Public Records for Evaluating Health Effects of Treated Sewage Sludge in North Carolina, 72 N.C. Med. J. 98 (2011), available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3136883/. Ultimately, the team concluded that: (1) “records constitute an important tool for public health investigation and exposure surveillance” and (2) better government records must be kept to monitor the risks posed by some types of municipal waste to growing populations.23Id. at *6.

Other examples of the benefits of open records may be less dramatic, but still illustrate how they enhance the public’s ability to understand or participate in their government. Generally, government agencies are not well equipped to provide information in a way that is easy to understand for a broad audience. Public access to information allows news media and non-governmental organizations to play an intermediary role by clarifying complicated facts and data sets for the broader public.24 Many nonprofits are chartered expressly to promote the purpose of public education. In that vein, Miami Waterkeeper offers the public information on water quality conditions around South Florida. To keep the information up-to-date, Miami Waterkeeper performs weekly water quality monitoring for select recreational areas around Biscayne Bay. Public records requests allow the organization to supplement its weekly monitoring, and cover a larger area, with additional data that the state government collects but does not regularly publish. Whenever Miami Waterkeeper requests this data, the state government charges a fee. As detailed above, a weekly fee of any size that is not included in the organization’s restricted budget could prevent Miami Waterkeeper from accurately updating the free water quality data and limiting public access to health information.

In addition, there are many laws that rely on members of the public to report issues to the government for proper enforcement.25Child Welfare Information Gateway, State Statutes (2019), https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/manda.pdf; Environmental Protection Agency, NPDES Self-Monitoring System User Guide (1985), https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyNET.exe/200049AL.txt?ZyActionD=ZyDocument&Client=EPA&Index=1981%20Thru%201985&Docs=&Query=&Time=&EndTime=&SearchMethod=1&TocRestrict=n&Toc=&TocEntry=&QField=&QFieldYear=&QFieldMonth=&QFieldDay=&UseQField=&IntQFieldOp=0&ExtQFieldOp=0&XmlQuery=&File=D%3A%5CZYFILES%5CINDEX%20DATA%5C81THRU85%5CTXT%5C00000002%5C200049AL.txt&User=ANONYMOUS&Password=anonymous&SortMethod=h%7C-&MaximumDocuments=1&FuzzyDegree=0&ImageQuality=r75g8/r75g8/x150y150g16/i425&Display=hpfr&DefSeekPage=x&SearchBack=ZyActionL&Back=ZyActionS&BackDesc=Results%20page&MaximumPages=1&ZyEntry=5; Report Scams or Frauds, usagov, (last visited Nov. 12, 2020), https://www.usa.gov/stop-scams-frauds. Concerned citizens are often the first to report pollutants like oil spills to governmental agencies.26In 2020, more than 80 pollution reports were received by Miami Waterkeeper from members of the public. Records on file with author. The issue here is follow-up. Too often, records requests are the only way the public can determine if the problem reported was addressed by the proper authority, whether through fines, enforcement actions, clean up, or otherwise. In this way, public records laws are essential to ensuring not just government accountability, but also appropriate government action and response.

These are just a few examples that demonstrate why broad access to government information matters. Prohibitive fees imposed upon organizations and individuals acting in the public interest diminish the records request process’ ability to promote civic accountability and transparency by keeping the public apprised of government activities. As the Supreme Court wrote years ago, “an informed citizenry [is] vital to the functioning of a democratic society.”27N.L.R.B., supra note 12, at 242.

II. Public Records Laws Across the United States

Before analyzing the effect of fee waiver policies, it is worth providing context to explain how public records request fees are treated across the fifty states and the federal government. Particular focus is given to Florida law as an example of a public records policy that does not incorporate fee waivers.

A. Florida

The Florida Constitution guarantees the right to inspect or copy any public record created at the state, county, or municipal levels of government.28Fla. Const. art. I, § 24. Even before the state constitution guaranteed this right, there were laws in Florida providing access to public records. See State v. City of Clearwater, 863 So. 2d 149, 152 (Fla. 2003) (noting that the first public records statute was enacted in 1909). However, Florida’s Public Records Act also allows governments to charge reasonable fees for responding to public records requests. If a Florida government is going to charge such a fee, it must: (1) let the requester know how much it will charge before it provides the public records, and (2) only charge fees to cover the actual costs of providing the records. Fees for copying public records are capped by statute and can only include the cost of materials or supplies used.29See Fla. Stat. Ann. § 119.07.

Where responding to a records request requires extensive labor or resources, governments can also use fees to cover those costs.30See Trout v. Bucher, 205 So. 3d 876, 878-79 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2016) (approving a fee based on the hourly wage of the specific employee fulfilling the public records request because the statute authorizes recovery of actual costs incurred). In the case of charging special service fees to cover an employee’s time, the government is still limited to charging fees that are reasonably based on the labor costs actually incurred to respond to the records request.31See Fla. Stat. Ann. § 119.07; Bd. of Cty. Comm’rs v. Colby, 976 So. 2d 31, 36 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2008) (costs can include costs for employee benefits as well as salaries). Although governments are expressly prohibited from profiting off of the public records process, the formula for calculating special service charges for extensive labor tends to vary between cities, counties, county departments, and state agencies.32See infra Part II.B. What counts as “extensive” can vary as well. One Florida court upheld fees under a policy that defined anything more than 15 minutes as “extensive” labor.33See Colby, 976 So. 2d at 35–37.

More common examples of requests that require truly extensive labor include requests for email communications or for documents that may contain sensitive personal information.34Similarly, some documents are simply too onerous to scan or photocopy without specialized equipment, such as hard copies of building plans, which can easily reach dimensions of 36” x 48” while being several inches thick. These records requests can require the government to review hundreds (or even thousands) of documents to prevent the disclosure of information like social security numbers and medical records.

As noted above, these fees can still become cost-prohibitive and bar access to all but the most well-funded records requesters even where there is not a lengthy review process to redact information protected by law or exempt from disclosure.35See Fla. Stat. Ann. § 119.07. Florida public records request fees, other than special service charges for extensive labor, are set and capped as follows: “$0.15 per one-sided copy for duplicated copies no larger than 14 x 8.5 inches; No more than an additional $0.05 for each double-sided copy; For all other copies, the actual cost of duplication, defined as “the cost of the material and supplies used to duplicate the public record, but does not include labor cost or overhead cost associated with such duplication.” Copies of county maps or aerial photos supplied by the County can include a reasonable charge for labor and overhead associated with duplication. Agencies can charge up to $1.00 for a certified copy of a public record. The custodian of public records may also charge a fee for remote electronic access, granted under a contractual arrangement with a user, that includes the direct and indirect costs of providing the access.

B. Other States

The purpose of this Article is to gauge the feasibility of implementing waivers for public records fees. Fortunately, existing state laws demonstrate that fee waiver policies are both common and can be implemented in a variety of forms, so governments can craft policies to meet their needs and the needs of the public.

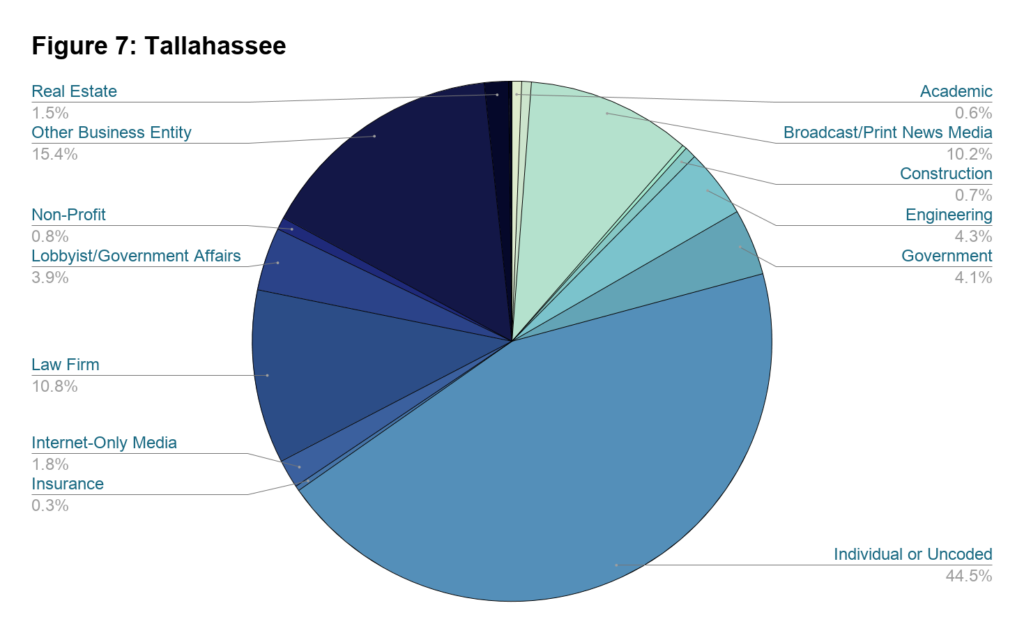

We surveyed state public records laws across the United States to produce the map in Figure 1.36See Appendix A.

Figure 1: The United States Categorized By Fee Waiver Type.

States fall into one of three categories: (1) mandatory, (2) discretionary, and (3) no waiver. “Mandatory” means that the state’s public records law requires that no fees be charged, or that fees be waived or reduced, in all or certain specified circumstances. “Discretionary” means that state agencies and local governments have some choice in whether to waive or reduce fees for records requests. “No waiver” means that the state’s public records law does not provide for fee waivers or reductions.

The vast majority of states’ public records laws allow for some form of fee waiver or fee reduction process.37Some states have very limited fee waivers. Arizona, for example, only waives fees for individuals who need public records to claim a benefit from the federal government. See Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 39-122 (LexisNexis 2020). Likewise, Hawaii does not waive fees completely but reduces fees when it serves the public interest. See Haw. Code R. § 2-71-1 (LexisNexis 2020). As shown in Figure 1 above, only nineteen states lack any type of waiver or exemption from public records fees.38The state laws that do not specifically address fee waivers are, nevertheless, relatively diverse. For example, California law does not include a fee waiver provision but allows individual state agencies and local governments to adopt their own records policies, which has enabled local governments to enact fee waivers of their own. See Cal. Gov’t Code § 6253 (Deering 2020); see, e.g., L.A. Admin. Code div. 12 ch. 2, https://urldefense.proofpoint.com/v2/url?u=http-3A__ens.lacity.org_clk_rmdroot_clkrmdroot1085140989-5F06082020.pdf&d=DwMFaQ&c=sJ6xIWYx-zLMB3EPkvcnVg&r=gMdtIVovaoc-J3hxgbf-9FAHX8x2shOkGtVWpUdwCRg&m=_p7itMrf04DriBcm0FS9R2jgabHeTE0SiKCvARaPyHQ&s=NiSyHIm1BdJkl7eM3bKvkL1yeT6m9JbqK-TguPQE-sE&e=. Likewise, Mississippi law does not provide a fee waiver but allows records custodians to “consider the type of information requested, the purpose or purposes for which the information has been requested and the commercial value of the information” when setting fees. Miss. Code Ann. § 25-61-7 (2019). Finally, Nebraska prohibits records custodians from charging attorney’s fees for the legal review of responsive documents. Neb. Rev. Stat. § 84-712 (LexisNexis 2020).

Of the states that do allow fee waivers, those waivers are granted under a variety of criteria and through different processes. Many states grant fee waivers to requesters based on whether the information is likely to be used for a public purpose. In Oklahoma, state law mandates that:

In no case shall a search fee be charged when the release of records is in the public interest, including, but not limited to, release to the news media, scholars, authors and taxpayers seeking to determine whether those entrusted with the affairs of the government are honestly, faithfully, and competently performing their duties as public servants.3951 Okl. St. § 24A.5. (emphasis added).

Illinois uses similar criteria but allows records custodians some discretion in granting fee waivers:

Documents shall be furnished without charge or at a reduced charge, as determined by the public body, if the person requesting the documents states the specific purpose for the request and indicates that a waiver or reduction of the fee is in the public interest. Waiver or reduction of the fee is in the public interest if the principal purpose of the request is to access and disseminate information regarding the health, safety and welfare or the legal rights of the general public and is not for the principal purpose of personal or commercial benefit. For purposes of this subsection, “commercial benefit” shall not apply to requests made by news media when the principal purpose of the request is to access and disseminate information regarding the health, safety, and welfare or the legal rights of the general public. In setting the amount of the waiver or reduction, the public body may take into consideration the amount of materials requested and the cost of copying them.405 ILCS 140/6(c) (emphasis added).

Occasionally, state laws require some oversight in the process of assessing fees for records requests. Massachusetts, for example, has a discretionary fee waiver provision.41Massachusetts law allows records custodians to waive or reduce fees if disclosure of a requested record is in the public interest, if the requester doesn’t have a commercial interest in the records, or if the requester lacks the financial ability to pay the full amount of the reasonable fee. See 950 C.M.R. 32.07(2)(k). However, local records custodians need to seek approval from the state government if they wish to impose fees beyond the statutory limit or need additional time to produce the documents requested.42See, e.g., 950 Mass. Code Regs. 32.07 (2020). Prior to 1984, Florida law required a similar procedure to set records request fees.43Ch. 79-187, § 4, at 726, Laws of Fla.; see Bd. of Cty. Comm’rs v. Colby, supra note 31. The state government’s role in setting records charges has since been eliminated and replaced with the requirement that fees be based on the salary rate of the personnel actually reviewing the record request. Ch. 81-245, § 1, at 989, Laws of Fla.; Ch. 84-298, § 5, at 1401, Laws of Fla.

The remainder of states with fee waiver policies also tend to focus on criteria like the requester’s ability to pay. Michigan requires an affidavit attesting to the requester’s indigence and includes some limits on the number of times a requester can receive discounted copies during the same calendar year.44Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 15.234 (2020). Maryland also examines the requester’s ability to pay but requires the requester to affirmatively ask for fees to be waived.45Md. General Provisions Code Ann. § 4-206 (2020).

Another criterion for some states’ fee waivers involves whether physical copies (as opposed to only digital files) are requested.46See, e.g., N. H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 91-A:4 (2020). Similarly, some states waive all fees where physical records are being inspected in-person but not copied.47See, e.g., Minn. Stat. Ann. § 13.03 (West 2019).

Finally, where a waiver of an entire fee is not granted, a few states have adopted provisions for fee reductions or waivers of charges affiliated with the first few hours of the records custodians’ work.48See, e.g., N.Y. Pub. Off. Law § 87; See also Haw. Code R. § 2-71-1 (LexisNexis 2020).

C. Federal Government

The Freedom of Information Act governs federal agencies’ responses to public records requests. FOIA requires fees to be waived, or reduced, for a public records request if: (1) the information requested will serve the public interest by significantly contributing to public understanding of government activities, and (2) it will not be used commercially.49Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), 5 U.S.C. § 552 (2018).

Although each federal agency drafts its own policies, fee schedules, and fee-waiver or fee-reduction procedures, the fee schedules must conform to guidelines promulgated by the Office of Management and Budget (“OMB”).505 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(A)(i). OMB has found that they only have authority to establish guidelines for charging fees and not when they should be reduced or waived. Beyond the plain statutory language outlined below, this authority is agency-specific. See Freedom of Information Reform Act of 1986, Pub. L. No. 99-570, §§ 1802-1804, 100 Stat. 3207, 3248-50 (1986); FOIA Fee Guidelines, 52 Fed. Reg. 10,012, 10,016 (Mar. 27, 1987). For OMB’s uniform fee schedule and guidelines, see id. at 10,017. These fees are generally limited to reasonable standard charges for document search and duplication.515 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(A)(ii). Only commercial requesters may be charged the cost of reviewing documents; specifically, for the purpose of determining if any information is exempt from disclosure.52Id. § 552(a)(4)(A)(ii)(II). Similar charges related to document review are typically a major expense in states that, like Florida, do not include fee waivers in their public records laws.

Likewise, federal agencies may not charge fees for the first two hours of searching or the first 100 pages of duplication unless the requester is using the information for commercial purposes.53Id. § 552(a)(4)(A)(iv)(II). In contrast, Florida governments commonly charge fees after the first fifteen or twenty minutes of work.54See City of Miami Administrative Policy, APM-4-11, at 5 (Feb. 2, 2015), available at http://archive.miamigov.com/employeerel/pages/CityAdminPolicies/APM/APM%204-11%20Public%20Records.pdf.

Under FOIA, fees are completely waived or reduced “if disclosure of the information is in the public interest because it is likely to contribute significantly to public understanding of the operations or activities of the government and is not primarily in the commercial interest of the requester.”555 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(A)(iii). For example, the Department of Defense has incorporated this “public interest fee waiver” requirement into its FOIA regulations.5632 C.F.R. § 286.12(l)(1) (2020). Under Department of Defense regulations, records must be furnished with charges waived, or at a reduced rate, when the following conditions are met: (1) the subject of the request concerns identifiable operations or activities of the federal government with a connection that is direct and clear, not remote or attenuated; (2) the disclosure of the requested information would contribute significantly to public understanding of those operations or activities by being meaningfully informative and by contributing to the understanding of a reasonably broad audience of interested persons; (3) the disclosure is not primarily in the commercial interest of the requester including a commercial, trade, or profit interest that would be furthered by the request.57Id. §§ 286.12(l)(2)(i)-(iii).

III. Proposed Fee Waiver Criteria for Florida Governments

Using FOIA as a model,58We selected FOIA as a model because: (1) it is a process that is broadly understood across the country and (2) it most directly serves the public interest. As will be discussed in the next section, it is also less likely to burden government records custodians. We propose the following criteria for state and local governments to consider waiving fees associated with public records requests:

- Where disclosure of the information is in the public interest because it is likely to contribute significantly to public understanding of the operations or activities of the government and is not primarily in the commercial interest of the requester; or

- Where the information is requested by educational, noncommercial scientific institutions, or any other person or organization that will not use information for commercial purposes; or

- The subject of the request concerns identifiable operations or activities of the government:

- With a connection that is direct and clear, not remote or attenuate; and

- The disclosure of the requested information would contribute significantly to public understanding of those operations or activities by being meaningfully informative and by contributing to the understanding of a reasonably broad audience of interested persons; and

- The disclosure is not primarily in the commercial interest of the requester including a commercial, trade, or profit interest that would be furthered by the request.59See 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(A)(iii).

This type of provision could certainly be enacted by state statute. However, under Florida law, there is nothing that would prevent local governments or state agencies from creating their own fee waiver policies without the need for a statewide, statutory amendment. Cities and counties, for example, could adopt these discretionary public-interest-fee-waiver criteria via a resolution to modify departmental practice, an ordinance to amend the local code, or even an administrative order.60See, e.g., Fees Charged to the Public for Examining and Duplicating Records, Miami-Dade County Administrative Order No. 4-48 (July, 24, 1990), http://www.miamidade.gov/aopdfdoc/aopdf/pdffiles/AO4-48.pdf (further defining county public records policies regarding fees charged to requesters).

If a waiver of the entire fee is not desirable, the criteria could be used to reduce fees or to waive fees for the first several hours of search time. Alternatively, fees could be entirely waived based on these criteria, with the exception of records requests that include physical documents and photocopying. The logic for limiting fees only to photocopies is simple: digital records involve fewer variable costs and are more easily distributed to a larger audience.

In Los Angeles, where fees are only imposed for physical copies, about 1,200 public records requests were made to the City Clerk’s Office over the course of one year. However, the online public records portal where Los Angeles publishes its digital records was accessed over two million times during the same period—more than a 150,000% increase.61Interview with LA City Clerk’s Office (on file with authors).

However, there is also a practical side of government records fees to consider. An important step in the public records request process is helping the requester narrow the parameters of their document search. Frequently, the request is not very specific when it is first submitted and a request that uses overly broad keywords and search terms can result in responses that contain thousands of pages of documents, creating a burden for public records custodians. Public records responses that include mountains of unnecessary or non-responsive documents rarely help the requester, serving only to create extra work for the government without benefiting the public at large. For that reason, records custodians sometimes use the specter of large fees to encourage requesters to narrow the scope of the information being sought. Unfortunately, using fees this way occasionally clashes with the primary objective of public records laws. It can force public-interest groups to abandon requests for documents that could be helpful but are too expensive (a predicament encountered by the authors even during the research for this Article) and prevent organizations that do not have the resources to pay for large data sets from accessing valuable government information.

In cases where the FOIA-inspired criteria can be satisfied, and any related fees waived, a simple reminder that the requester will have to pour through voluminous records may be enough of a nudge to narrow the request considerably. Likewise, an individual or organization eligible for a fee waiver under these criteria is unlikely to have the capacity to repeatedly sift through deluges of irrelevant data.

Our recommendation is for states and municipalities to customize the FOIA-inspired criteria, and the information contained in the next sections, to: (1) better calibrate how government labor and resources are allocated while (2) serving the public’s interest in transparent and accountable governance by removing, where appropriate, barriers to accessing government information. After all, the intent of Florida’s public records law explicitly states “all state, county, and municipal records are open for personal inspection and copying by any person,” rather than any person that can afford it.62Fla. Stat. § 119.01(1) (2020) (emphasis added).

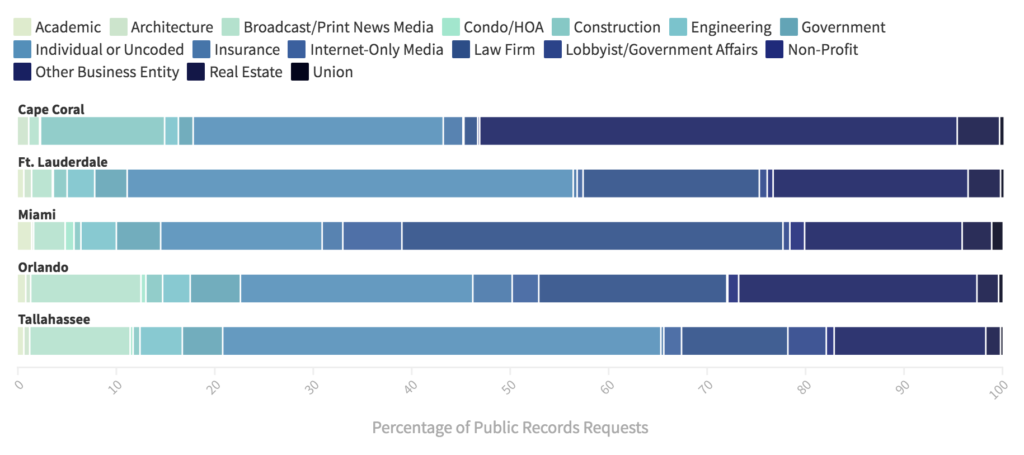

IV. Analysis of Public Records Requests across Five Florida Cities

To determine whether or not a fee waiver based on the FOIA-inspired criteria would burden Florida municipalities, we conducted a limited study of records requests to review which requests would quality for the fee waiver. In order to accomplish this, we obtained logs of requests for public records made between January 2019 and May 2020 for the following cities in Florida: Cape Coral, Fort Lauderdale, Miami, Orlando, and Tallahassee.63We chose these five cities because: (1) they are among the ten most populous cities in Florida and (2) they use software to track their public records requests, making it possible for us to obtain and review their request logs. It is worth noting that not every local government uses such software.

For each log entry, we attempted to categorize the identity of the person or organization making the request. For our purposes, records requesters were placed in one of the following categories:

- Academic: includes requesters linked to academic institutions. Whenever possible, we attempted to verify that the request was made for a research purpose.

- Architecture Firm: includes businesses primarily providing architectural services like planning and design for building construction.

- Broadcast/Print News Media: includes organizations in the field of journalism that primarily distribute content through print newspapers, television, or radio stations.

- Condominium Association/Neighborhood Association/Homeowners Association: includes any organized group of residents or property owners related to a specific, geographic community.

- Construction Industry: includes businesses primarily providing labor and expertise to erect buildings, roads, and other infrastructure.

- Engineering Industry: includes businesses primarily providing engineering services across a variety of more specialized fields.

- Government: includes government agencies of all sizes.

- Individual or Uncoded: refers to requests made by individuals unaffiliated with another organization or business as well as instances where we were unable to verify the requester’s affiliation or where the requester was anonymous.

- Insurance Company: refers to a business primarily providing insurance policies.

- Internet-Only Media: includes bloggers and media outlets, whether journalistic or not, that primarily distribute content online.

- Law Firm: includes any attorney or paralegal in private practice.

- Lobbyist/Government Affairs: refers to professionals, whether employed at an independent firm or by a larger company, who primarily provide services aimed at influencing government policy. These requesters were not compared against lobbyist registrations, only company websites and job descriptions.

- Non-Profit Organization: includes tax-exempt organizations whether affiliated with religious, political, educational, or other social causes.

- Other Business Entity: includes any for-profit entity not covered by one of the other categories.

- Real Estate Industry: includes realtors and real estate developers.

- Union: includes any association of workers forming a legally recognized bargaining unit.

To be clear, this analysis only included cities in Florida and no other local governments like counties, special districts, or state agencies. Nevertheless, it covers thousands of records requests for each jurisdiction.

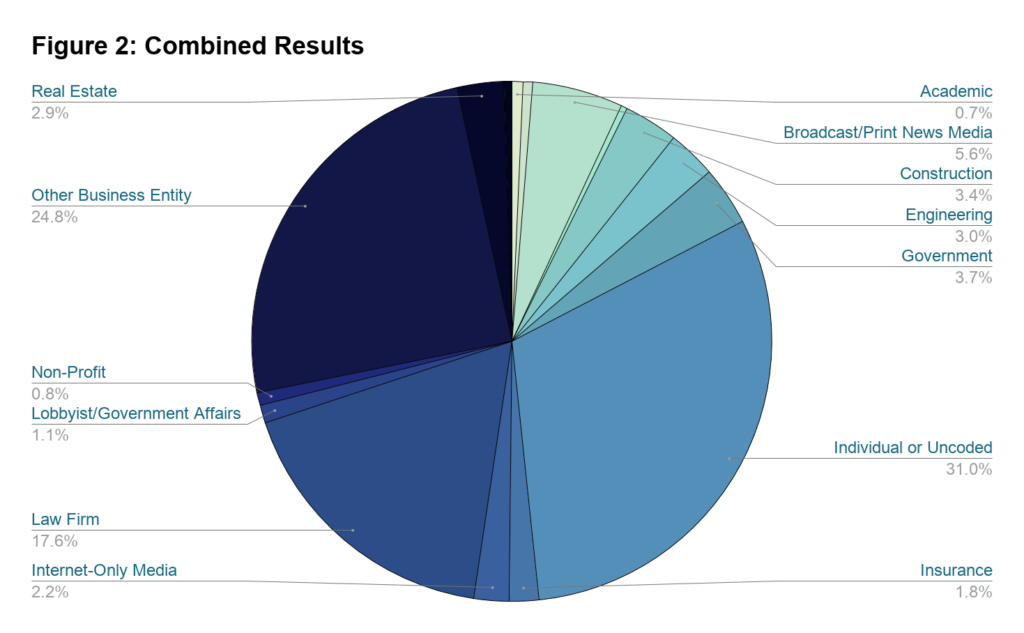

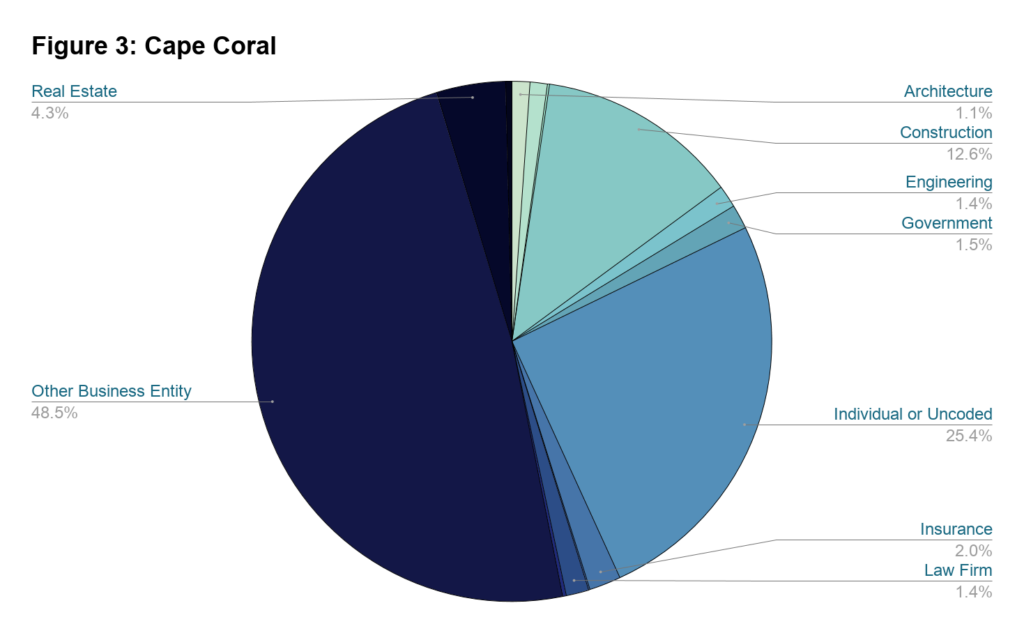

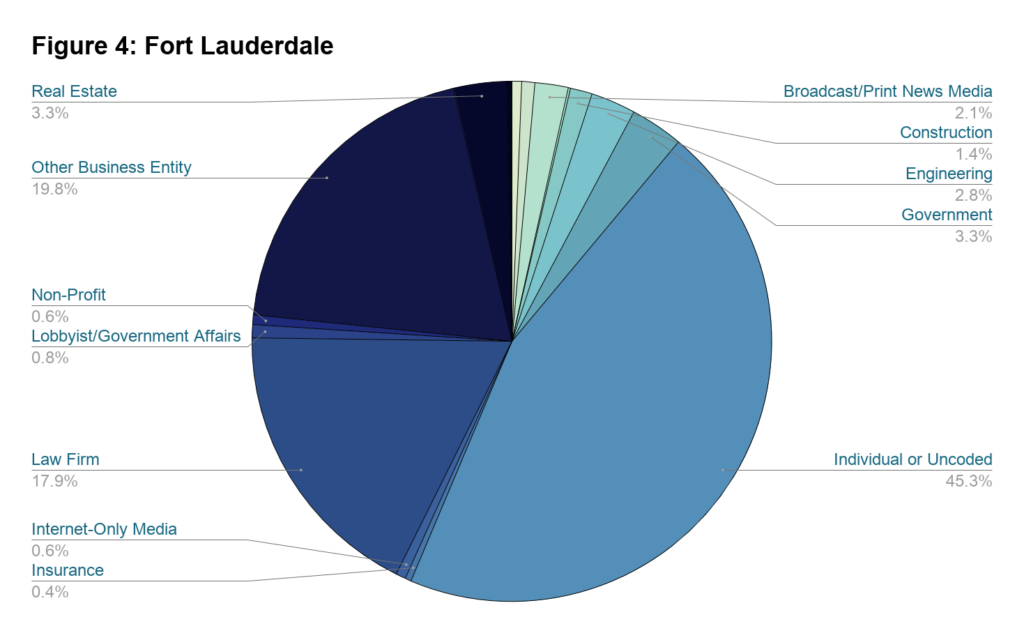

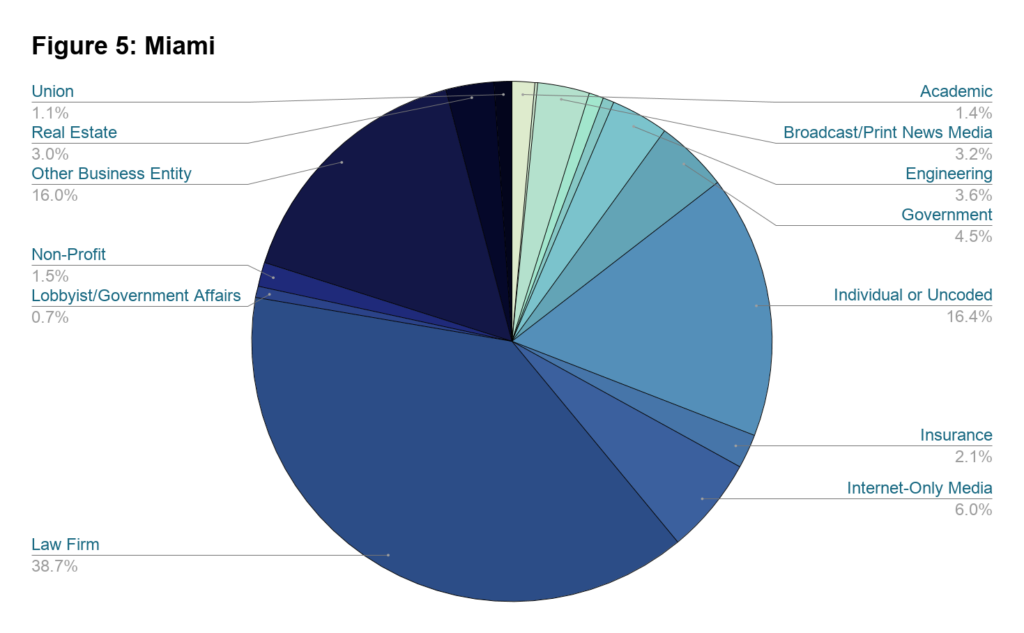

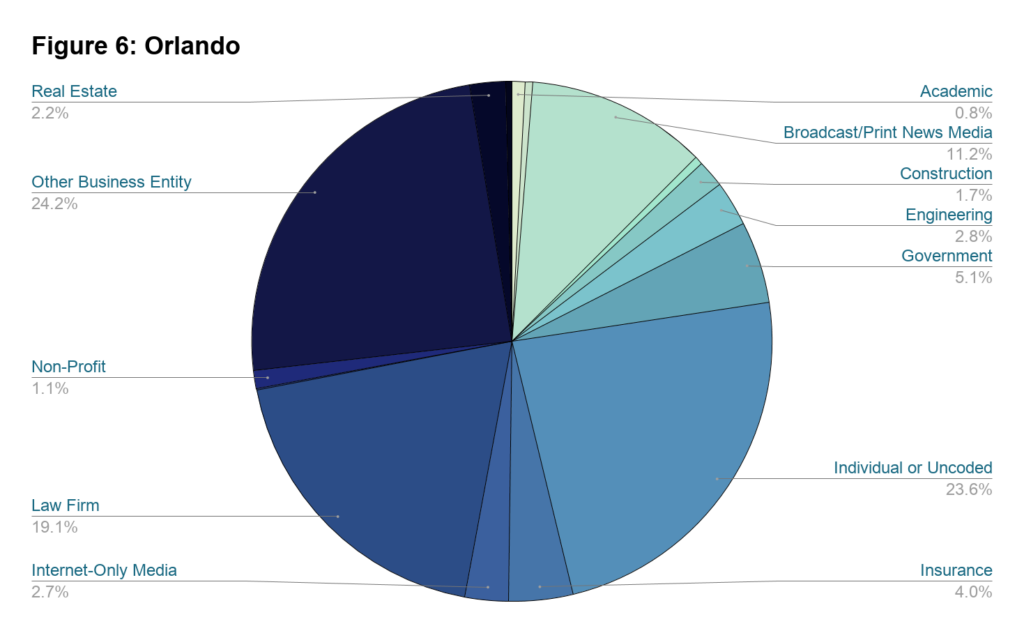

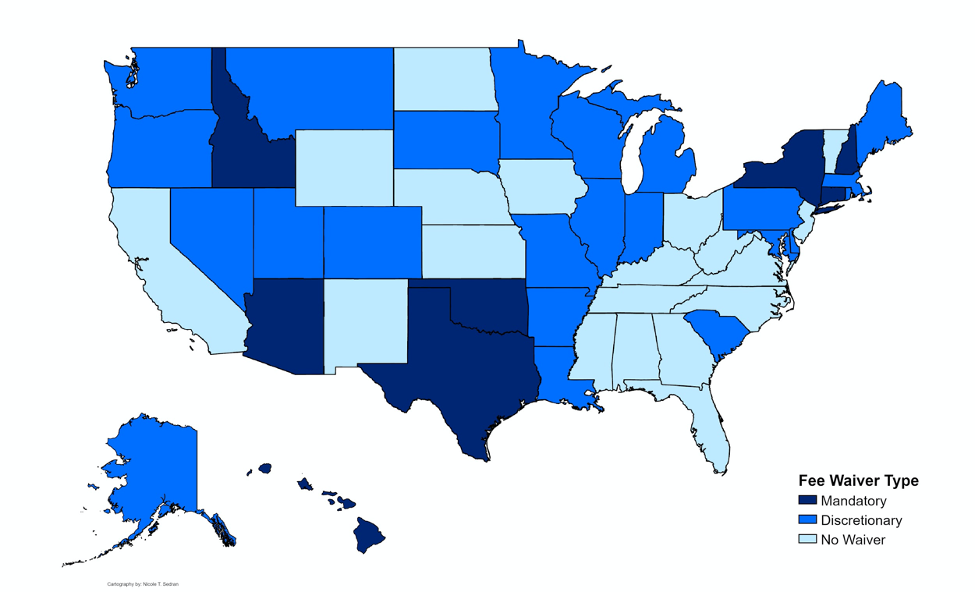

Each log entry represented an individual request for public records, meaning that one person or entity could appear in the log multiple times.64Note that Figure 2 is an average of the results for each category across the five Florida cities listed above. The mean rates of records requests per category are presented to illustrate how frequently certain community segments seek government documents. The averages in this figure are not weighted by municipal population size nor are they intended to predict specific outcomes. Instead, they are intended to help guide policy discussion surrounding the feasibility of waiving records fees for requests submitted by public interest entities. Accordingly, our results do not mean that most requesters fall into a specific category, but that most requests are made by individuals or organizations in those categories.65The percentages displayed in the pie charts are rounded up to the nearest tenth of a percent for the sake of simplicity.

Figure 8: Comparison of Public Records Requests Across Five Florida Cities

As another disclaimer, the records request logs included in this analysis omit requests made directly to the cities of Miami’s and Tallahassee’s police departments, as we did not have access to those documents.66The log we received is maintained by the Miami City Attorney’s Office on behalf of all city departments and does include many requests for police records. Similarly, the log we received from Tallahassee is maintained by city hall but does not include direct requests made on the police department. Likewise, the quality of data provided by each jurisdiction was not the same. In some cases, we were able to access the text of the request, in others, only the date of the request and name of the requester. Hence, the varying level of detail we received for each request affected our ability to apply a category in some instances. Where there was not enough information to make a determination, the label “Individual or Uncoded” was applied.67The relative size of the Individual or Uncoded category is a rough, but imperfect, indicator of the quality of data we received. Cities with a larger percentage of Individual or Uncoded category requests typically included less information in their logs. Additionally, the data for this analysis was processed by a research team. While data was reconciled and reviewed, a certain degree of individual bias is likely present in the coding of the records requests. Finally, the last few months of requests included in the logs took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic’s effect on public records requests, if any, is unclear.

V. Impact of Fee Waivers

A. Populations Most Likely to Benefit in Florida

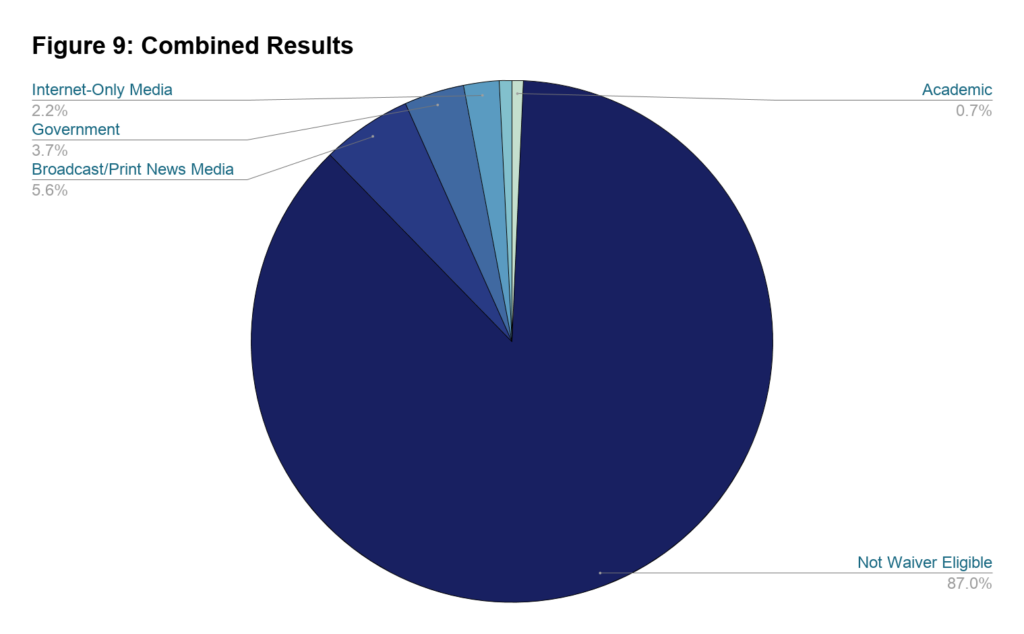

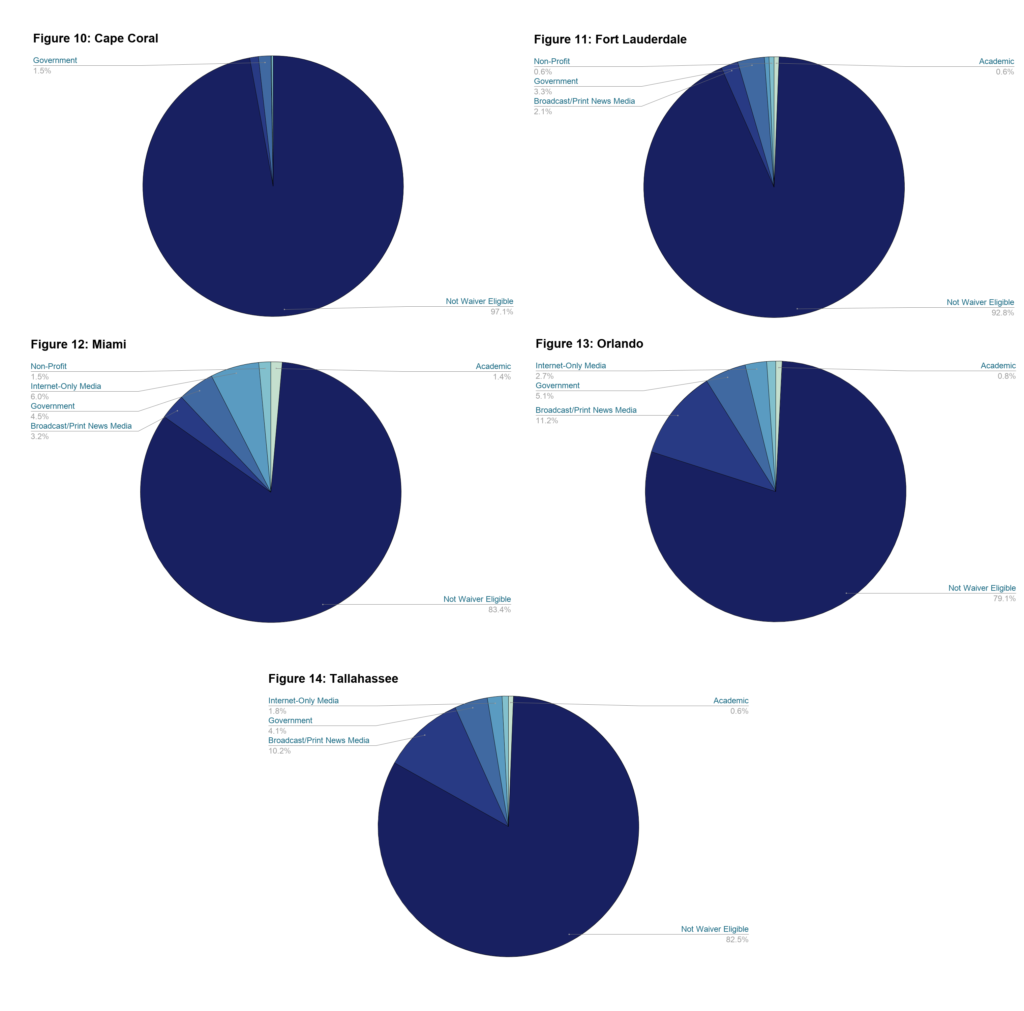

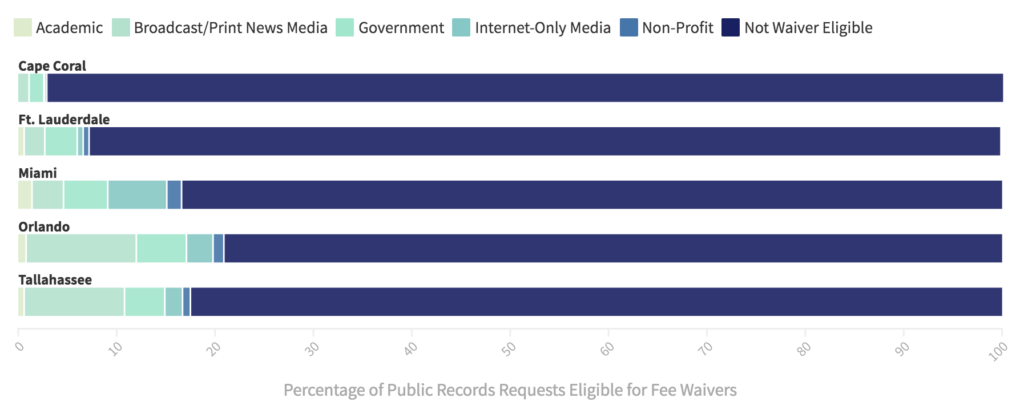

Based on the FOIA-inspired criteria proposed in Section III of this Article, most public records requests in the five cities we surveyed would not be eligible for a fee waiver.

On average, only 13% of requests across these cities would be likely to have their fees waived.68Again, this analysis only speaks to the number of requests made and not the amount of government labor required to respond to any individual request. Note also that Figure 9 is an average of the results for each category across the five Florida cities surveyed in this Article. As with Figure 2, it is not weighted by municipal population size nor is it intended to predict specific outcomes. Instead, the averages are intended to help guide policy discussion surrounding the feasibility of fee waivers for public interest entities. But for those that would become eligible, fee waivers would improve access to government information and support the goals of government transparency and accountability.69Government records are already less likely to receive public scrutiny as the decline of the news industry has left news outlets unable to cover the litigation costs associated with fighting for public access to records and government transparency. Amy Taxin, Amid decline, newspapers press less for records in court, AP News (Mar. 15, 2020), https://apnews.com/13ea494a8d9bcc201eef34a5c8cfff51.

In our analysis, we assumed that the following categories would most likely be eligible for fee waivers:

- Academic

- Broadcast/Print News Media

- Government

- Non-Profit Organization

The Internet-Only Media category was also included even though many bloggers and online content producers blur the lines between individuals, entertainment companies, and news organizations. Nevertheless, many traditional news organizations have switched to distribute journalism solely online and even individual podcasts and YouTube channels now reach and inform large audiences. Because the FOIA-inspired waivers are subject to record custodians’ discretion, it is possible that some requesters in this category could receive a waiver where others in the same category (as we applied it) would not.

Overall, we believe these categories of public records requests would qualify under the FOIA-inspired criteria for fee waivers because they are “likely to contribute significantly to public understanding of the operations or activities of the government” and contribute significantly to public understanding of those operations or activities by being meaningfully informative and by contributing to the understanding of a reasonably broad audience of interested persons.70See 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(A)(iii). Of note is that these entities are non-commercial interests (with the exception of some news media) with large audiences, broad constituencies, and obligations to educate, inform, and advise the general public. Therefore, any fee waiver benefiting these categories of requester would most likely benefit the general public as well.

Accordingly, we concluded that the other categories like Condominium Association/Neighborhood Association/Homeowners Associations, Unions, anonymous requesters, individual requesters unaffiliated with a public interest entity, and any of the various commercial (non-news media) entities would be less likely qualify for a FOIA-style fee waiver because a benefit to a large swath of the general public was not as clear. In short, these categories are less likely to be able to demonstrate a public interest as characterized under FOIA.

Figure 15: Comparison of Fee Waiver Eligibility Across Five Florida Cities

Comparing each of these categories, most groups likely to receive a fee waiver appeared to request public records at similar rates across the five cities we surveyed – except for Broadcast/Print News Media, which varied significantly.

There was also a notable amount of variation in the number of requests made by Internet-Only Media requesters, with the City of Miami as the primary outlier.71The Law Firm category also varied notably across the five cities we surveyed. Nevertheless, in each jurisdiction, law firms always accounted for a relatively large percentage of records requests. However, a single requester drove this variation by making 65% of the requests that fell under the Internet-Only Media category in the City of Miami.72Individuals making large numbers of public requests is not unique to Miami. In Cape Coral, for example, a swimming pool contractor made almost 1,000 requests for records.

Since most categories likely to qualify for waivers were requested at fairly consistent rates across cities, the percentage of requests eligible for a FOIA-inspired fee waiver will probably remain small in similar jurisdictions. Nevertheless, the next section will show that fee waivers – when applied in practice – do not seem to increase the burden on government records custodians regardless of the actual number of fee waiver-eligible requests.

B. Governments with Fee Waiver Policies are Not Overwhelmed by Records Requests

During the summer of 2020, we interviewed public records custodians and records management officers (hereinafter “records custodians”) from the following cities: Baton Rouge, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, and Los Angeles.73The results of these interviews are (1) anecdotal, (2) reflect the experiences of government officials serving larger U.S. cities, and, (3) in some instances, reflect the experiences of officials serving only one municipal department as opposed to an entire city. We selected these six cities for their regional diversity, population size, and the mix of policies related to fee waivers that they have adopted.

Anecdotally, the records custodians’ experiences did not demonstrate fee waivers contributing to abuse of the public records request process. Across these cities, records custodians reported that most records requests either were not charged fees (because local policy did not apply fees) or had their fees waived. For example, Dallas reported that 90% of requests had their fees waived, Boston stated that over half were not charged a fee, and Los Angeles primarily charged fees when photocopying physical documents.74This is in contrast to jurisdictions that also charge for staff time. Los Angeles also includes a fee waiver policy exempting records requests from government agencies. L.A., Cal., Administrative Code div. 12, ch. 2, § 12.41 (1999).

In fact, many of the records custodians we interviewed did not initially understand the idea of a “fee waiver” because their governments do not impose fees in the first place. Of these six cities, only Denver appears to consistently apply fees despite the discretionary waivers permitted by its state law.75Colo. Rev. Stat. § 24-72-205(4) (2016). Denver’s policy is that the first hour of research is always free. Subsequent hours are charged at a rate of $33/hour. The city officials we interviewed stated that the vast majority of requests are able to be completed within the first free hour.

Likewise, with only one exception, these records custodians signaled broad support for fee waivers.76The Dallas records custodian we interviewed preferred to eliminate fee waivers to prevent any potential for abuse or favoritism in the records process. However, the same official also stated that: (1) fee waivers had not been abused in Dallas, (2) there are no disadvantages to fee waivers, and (3) fee waivers cut down on the amount of time spent processing payments, allowing the city to provide information to requesters more quickly. See Dallas Interview (on file with authors). Two cities’ officials even stated that collecting fees for public records requests was more trouble than it is worth.77See Boston and Chicago Interviews on file with authors. There were more differences among the records custodians when it came to the question of which type of fee waiver policy is most beneficial: some preferred the flexibility granted by discretionary policies while others preferred the fairness — as well as the simplicity — that mandatory fee waivers provide.78See all interviews on file with authors

Overall, fee waivers appear to neither create nor solve problems for government records custodians, except for the issue of collecting fees. The challenges posed by the public records response process are fundamentally the same in each city we studied regardless of whether or not fees are charged to requesters (and whether fee waivers are mandatory or discretionary). Often, the primary concern is the amount of labor required, and the time allotted, to respond to records requests. Based on our research, fee waiver policies do not appear to impact records custodians’ work one way or the other.

Across the cities we analyzed and interviewed, the number of requests did not seem to vary based on the availability of fee waivers.79Again, these numbers may not all be direct comparisons because some of the cities we researched, both inside and outside of Florida, do not have centralized departments for responding to records requests. Hence, some of the numbers reported could be missing requests made directly to other municipal departments. Additionally, the records collected for Florida cities are not annual numbers, but rather 1.25 years’ worth of records. Two of the cities outside of Florida where we interviewed officials reported a larger number of annual records requests than those catalogued by the Florida cities we reviewed. Another two of the cities outside of Florida reported annual records requests at a lower number than the Florida cities we reviewed.

Ultimately, the difference between cities that allow fee waivers and those that do not is whether the public has to pay to access government documents.

VI. Conclusion

In Florida, and 18 other states,80These 19 states account for 131 million people. State Population Totals and Components of Change: 2010-2019, U.S. Census Bureau (last updated Dec. 19, 2019), https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-state-total.html. the law permits governments to recover a fee in exchange for government documents but does not provide a legal process to waive those fees when it benefits the public.81In practice, many Florida governments will decide to waive fees for individual public records requests. All five Florida cities provided their request logs without charge for example. But without a formal policy in place, these ad hoc fee waivers are applied inconsistently. When governments charge these fees to access public records, it creates a barrier to access for individuals and organizations without the funds to pay.

Adding a fee waiver policy to records request laws removes that financial barrier to accessing records. Moreover, these waivers can be tailored to serve the public interest without burdening government agencies. Already, the majority of states (and the federal government) have adopted some version of a fee waiver into their laws regulating public records requests.

Further, our limited study found no evidence that fee waivers negatively impact the public records process. In firsthand interviews with records custodians in the cities of Baton Rouge, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, and Los Angeles we learned that each of these cities has adopted a distinct approach to fee waivers. Similarly, each receives varying amounts of records requests on an annual basis (from approximately 1,000 requests per year to almost 50,000 per year), and each one grants fee waivers at vastly different rates. In spite of this diversity, none of the government officials we interviewed had encountered a situation where their government’s fee waiver policy had been abused.

In general, we recommend a policy modeled after the fee waiver provisions in the federal Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) because it is broadly understood and focuses on the public interest.82Nevertheless, state and, where appropriate, local government policymakers could also adopt fee waivers based on alternative criteria like cases of indigence, news organizations with a certain threshold of circulation, or simply remove fees for producing any digital files not provided in hard copy. Using FOIA’s specific criteria for granting fee waivers as our example, we analyzed over a year’s worth of public records requests across five Florida cities. In each case, we determined that the vast majority of municipal records requests made for those cities would not have qualified under the federal government’s fee waiver criteria. The relatively small number of requests that would be eligible for such a fee waiver suggests that it is a policy that would be practically feasible to implement.83The common thread throughout our conversations with government officials about the public records process, regardless of whether they had a fee waiver policy in place, was their concern related to person-hours expended, compliance with statutory deadlines, and litigation exposure for failure to comply. Our research indicates that fee waivers would have little impact on these government operations one-way or the other.

Overall, the analysis in this Article demonstrates that fee waivers pose little risk to governments. In fact, they appear to be a common policy in the United States: some governments, such as Dallas, waive fees for as many as 90% of all records requests.84See Dallas Interview (on file with authors). Likewise, the evidence did not suggest a relationship between the adoption of fee waivers and the number of requests received by a government.

Although fee waivers do not seem to affect the burdens shouldered by government records custodians, there are many policies and resources that could simplify the work of responding to requests for documents. For instance, states could set up grants to help local governments invest in e-discovery software to facilitate the review of potentially responsive documents—a process that is normally very time consuming and costly. Alternatively, open data and open document websites can remove the need for numerous requests by proactively publishing government records and data sets online. In Los Angeles, the city’s open document portal was visited over two million times in one year whereas records requests numbered in the mere thousands. Likewise, many governments already use specialized software, like GovQA, JustFOIA, NextRequest, etc., to streamline the process of managing incoming public records requests.85Many of the findings in this Article would not have been possible if the cities of Cape Coral, Ft. Lauderdale, Miami, Orlando, and Tallahassee did not use this type of software to log the requests they receive.

Public records laws are a critical mechanism to maintain government accountability and support citizen involvement in government decision-making. The real-world consequences of restricting access to that information can range from serious to routine but, in all cases, result in a less informed citizenry. Fee waivers offer a simple and flexible solution. Lawmakers can use the information contained in this Article to craft policies that effectively allocate government resources and labor while promoting transparent and accountable governance by granting waivers to those pursuing documents in the public interest.

Kelly Cox, General Counsel, Miami Waterkeeper & Adjunct Faculty Member, University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science

Matthew Haber, Esq.

Suggested Citation: Kelly Cox & Matthew Haber, Does Freedom of Information Mean “Free”? How the Hidden Costs of FOIA and Open Records Laws Impact the Public’s Ability to Request Government Documents, N.Y.U. J. Legis. & Pub. Pol’y Quorum (2020).

- 1Kelly Cox is a graduate of the University of Miami School of Law, Class of 2016. She is the General Counsel at Miami Waterkeeper & Adjunct Faculty Member at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science. Kelly is deeply grateful to her co-author Matthew Haber, Daniel Parobok, Susie Cox, Jim Porter, Brett Brumund, and the staff of Miami Waterkeeper for their support in developing this paper. She also wishes to thank the editorial board and staff of this law review for their work.

- 2Matthew Haber is a graduate of Duke University School of Law, Class of 2013, whose practice focuses on local government and administrative law. He helped build the City of Miami’s first Public Records Division and oversaw training for all of the city’s employees on fulfilling citizen requests for public records. Matthew is deeply grateful to his co-author Kelly Cox, Joseph Pulido, Jihan Soliman, Xavier Alban, Professor Dan Smith, and the public records custodians at Baton Rouge, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, and Los Angeles for making themselves available for interviews. He would also like to thank the officials at Cape Coral, Ft. Lauderdale, Miami, Orlando, and Tallahassee for providing their public records request logs.

- 3[1] Both authors would like to thank our University of Florida research team for countless hours of public records review and attention to detail: Amanda J. Acevedo, Tara S. Garner, and Marcos J. Izquierdo. Thanks are also due to Jessica Dennis, Casey Dresbach, Nicole Sedran, and Meagan Collins for their research and mapping assistance.

- 4Soucie v. David, 448 F.2d 1067, 1080 (D.C. Cir. 1971).

- 5Prior to the enactment of FOIA, many states already had regulations on the books pertaining to public records. Florida was an early adopter, enacting its first public records law in 1909. See Office of the Attorney General of Florida, Open Government — The “Sunshine” Law, available at https://myfloridalegal.com/pages.nsf/Main/DC0B20B7DC22B7418525791B006A54E4#:~:text=Florida%20began%20its%20tradition%20of,unless%20specifically%20exempted%20by%20the. Other states also enacted open records laws before FOIA: Louisiana lawmakers enacted the Public Records Act in 1940, New Mexico’s Open Records Law was enacted in 1947, Pennsylvania’s Right to Know Act was originally adopted in 1957, and Maine’s Freedom of Access Act was enacted in 1959. Sophie Winkler, Nat’l Ass’n of Counties, Open Records Laws: A State by State Report (2010), https://www.governmentecmsolutions.com/files/124482256.

- 6John Bonine, Public-Interest Fee Waivers Under the Freedom of Information Act, 1980 Duke L. Rev. 213, 214-15 (1981), https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2768&context=dlj.

- 7Id. at 215 n.7.

- 8Id. at 216; see generally United States Department of Justice, Create a FOIA Report, available at https://www.foia.gov/data.html (last accessed Dec. 14, 2020).

- 9See Jennifer Casacchia, 7 Things Every Nonprofit Should Know About Restricted Assets, American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Blog (Mar. 30, 2018), https://blog.aicpa.org/2018/03/7-things-every-nonprofit-should-know-about-restricted-assets.html; Greg McRay, Are You Misappropriating Your Nonprofit’s Funds?, Foundation Group (Mar. 23, 2017), https://www.501c3.org/misappropriating-nonprofit-funds/.

- 10See generally Miami Waterkeeper, www.miamiwaterkeeper.org.

- 11Invoice on file with the authors. The data requested was pre-existing in digital format, and no printing or copying was necessary in order to respond to this request. Additional legal review of these documents would have likely increased the cost of this request.

- 12Request on file with authors.

- 13See Miami Waterkeeper annual budget on file with authors. In 2017, 11% of MWK’s operating budget was discretionary. In 2017, 2% was discretionary. In 2018, 3% was discretionary. In 2019, 1% was discretionary. In 2020, 9% is discretionary.

- 14See invoices on file with authors.

- 15N.L.R.B. v. Robbins Tire & Rubber Co., 437 U.S. 214, 242 (1978).

- 16Daniel Berliner, Alex Ingrams & Suzanne J. Piotrowski, The Future of FOIA in an Open Government World: Implications of the Open Government Agenda for Freedom of Information Policy and Implementation, 63 Vil. L. Rev. 867, 869 (2019).

- 17See, e.g., Indiana Department of Health, Diseases Involving Sewage (last visited Nov. 8, 2020), https://www.in.gov/isdh/22963.htm. Ultimately, the county charged a total fee of $450.71 for the digital records (which were primarily emails). This amount, although reduced, was still almost 1.4% of Miami Waterkeeper’s discretionary budget. Invoices on file with authors.

- 18See Ben Popken & Andrew W. Lehren, Judge Orders Trump Administration to Reveal PPP Loan Data It Sought to Obscure, NBC News (Nov. 6, 2020), https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/judge-orders-trump-administration-reveal-ppp-loan-data-it-sought-n1246792.

- 19See Ben Popken & Andrew W. Lehren, Release of PPP Loan Recipients’ Data Reveals Troubling Patterns, NBC News (Dec. 2, 2020), https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/release-ppp-loan-recipients-data-reveals-troubling-patterns-n1249629 (explaining that tenants of President Trump and his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, may have benefitted disproportionately from loan disbursements that, in turn, went to pay rent owed to them).

- 20Contamination from the Flint River harmed more than 100,000 residents, causing an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease, among other illnesses. See Anya Smith et al., Multiple Sources of the Outbreak of Legionnaires’ Diseases in Genesee County, Michigan, in 2014 and 2015, 127 Envtl. Health Persp., (2019), available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6957290.

- 21Ron Fonger, Expert Says TTHM Levels in Flint Water Were Immediate Evidence of Trouble Ahead, MLive, (last updated Jan. 30. 2019), https://www.mlive.com/news/flint/2018/08/expert_says_initial_tests_were.html; Jonathan Oosting, Jim Lynch & Chad Livengood, ‘Disaster’ Warning Preceded Flint Water Switch, Detroit News, (Mar. 10, 2016), https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/politics/2016/03/10/disaster-warning-preceded-flint-water-switch/81629048/; Oona Goodin-Smith, State Health Chief Gave Different Timelines of Flint’s Legionella Outbreak, MLive, (last updated Jan. 19, 2019).

- 22See Alexander Keil, Steven Wing & Amy Lowman, Suitability of Public Records for Evaluating Health Effects of Treated Sewage Sludge in North Carolina, 72 N.C. Med. J. 98 (2011), available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3136883/.

- 23Id. at *6.

- 24Many nonprofits are chartered expressly to promote the purpose of public education. In that vein, Miami Waterkeeper offers the public information on water quality conditions around South Florida. To keep the information up-to-date, Miami Waterkeeper performs weekly water quality monitoring for select recreational areas around Biscayne Bay. Public records requests allow the organization to supplement its weekly monitoring, and cover a larger area, with additional data that the state government collects but does not regularly publish. Whenever Miami Waterkeeper requests this data, the state government charges a fee. As detailed above, a weekly fee of any size that is not included in the organization’s restricted budget could prevent Miami Waterkeeper from accurately updating the free water quality data and limiting public access to health information.

- 25Child Welfare Information Gateway, State Statutes (2019), https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/manda.pdf; Environmental Protection Agency, NPDES Self-Monitoring System User Guide (1985), https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyNET.exe/200049AL.txt?ZyActionD=ZyDocument&Client=EPA&Index=1981%20Thru%201985&Docs=&Query=&Time=&EndTime=&SearchMethod=1&TocRestrict=n&Toc=&TocEntry=&QField=&QFieldYear=&QFieldMonth=&QFieldDay=&UseQField=&IntQFieldOp=0&ExtQFieldOp=0&XmlQuery=&File=D%3A%5CZYFILES%5CINDEX%20DATA%5C81THRU85%5CTXT%5C00000002%5C200049AL.txt&User=ANONYMOUS&Password=anonymous&SortMethod=h%7C-&MaximumDocuments=1&FuzzyDegree=0&ImageQuality=r75g8/r75g8/x150y150g16/i425&Display=hpfr&DefSeekPage=x&SearchBack=ZyActionL&Back=ZyActionS&BackDesc=Results%20page&MaximumPages=1&ZyEntry=5; Report Scams or Frauds, usagov, (last visited Nov. 12, 2020), https://www.usa.gov/stop-scams-frauds.

- 26In 2020, more than 80 pollution reports were received by Miami Waterkeeper from members of the public. Records on file with author.

- 27N.L.R.B., supra note 12, at 242.

- 28Fla. Const. art. I, § 24. Even before the state constitution guaranteed this right, there were laws in Florida providing access to public records. See State v. City of Clearwater, 863 So. 2d 149, 152 (Fla. 2003) (noting that the first public records statute was enacted in 1909).

- 29See Fla. Stat. Ann. § 119.07.

- 30See Trout v. Bucher, 205 So. 3d 876, 878-79 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2016) (approving a fee based on the hourly wage of the specific employee fulfilling the public records request because the statute authorizes recovery of actual costs incurred).

- 31See Fla. Stat. Ann. § 119.07; Bd. of Cty. Comm’rs v. Colby, 976 So. 2d 31, 36 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2008) (costs can include costs for employee benefits as well as salaries).

- 32See infra Part II.B.

- 33See Colby, 976 So. 2d at 35–37.

- 34Similarly, some documents are simply too onerous to scan or photocopy without specialized equipment, such as hard copies of building plans, which can easily reach dimensions of 36” x 48” while being several inches thick.

- 35See Fla. Stat. Ann. § 119.07. Florida public records request fees, other than special service charges for extensive labor, are set and capped as follows: “$0.15 per one-sided copy for duplicated copies no larger than 14 x 8.5 inches; No more than an additional $0.05 for each double-sided copy; For all other copies, the actual cost of duplication, defined as “the cost of the material and supplies used to duplicate the public record, but does not include labor cost or overhead cost associated with such duplication.” Copies of county maps or aerial photos supplied by the County can include a reasonable charge for labor and overhead associated with duplication. Agencies can charge up to $1.00 for a certified copy of a public record. The custodian of public records may also charge a fee for remote electronic access, granted under a contractual arrangement with a user, that includes the direct and indirect costs of providing the access.

- 36See Appendix A.

- 37Some states have very limited fee waivers. Arizona, for example, only waives fees for individuals who need public records to claim a benefit from the federal government. See Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 39-122 (LexisNexis 2020). Likewise, Hawaii does not waive fees completely but reduces fees when it serves the public interest. See Haw. Code R. § 2-71-1 (LexisNexis 2020).

- 38The state laws that do not specifically address fee waivers are, nevertheless, relatively diverse. For example, California law does not include a fee waiver provision but allows individual state agencies and local governments to adopt their own records policies, which has enabled local governments to enact fee waivers of their own. See Cal. Gov’t Code § 6253 (Deering 2020); see, e.g., L.A. Admin. Code div. 12 ch. 2, https://urldefense.proofpoint.com/v2/url?u=http-3A__ens.lacity.org_clk_rmdroot_clkrmdroot1085140989-5F06082020.pdf&d=DwMFaQ&c=sJ6xIWYx-zLMB3EPkvcnVg&r=gMdtIVovaoc-J3hxgbf-9FAHX8x2shOkGtVWpUdwCRg&m=_p7itMrf04DriBcm0FS9R2jgabHeTE0SiKCvARaPyHQ&s=NiSyHIm1BdJkl7eM3bKvkL1yeT6m9JbqK-TguPQE-sE&e=. Likewise, Mississippi law does not provide a fee waiver but allows records custodians to “consider the type of information requested, the purpose or purposes for which the information has been requested and the commercial value of the information” when setting fees. Miss. Code Ann. § 25-61-7 (2019). Finally, Nebraska prohibits records custodians from charging attorney’s fees for the legal review of responsive documents. Neb. Rev. Stat. § 84-712 (LexisNexis 2020).

- 3951 Okl. St. § 24A.5. (emphasis added).

- 405 ILCS 140/6(c) (emphasis added).

- 41Massachusetts law allows records custodians to waive or reduce fees if disclosure of a requested record is in the public interest, if the requester doesn’t have a commercial interest in the records, or if the requester lacks the financial ability to pay the full amount of the reasonable fee. See 950 C.M.R. 32.07(2)(k).

- 42See, e.g., 950 Mass. Code Regs. 32.07 (2020).

- 43Ch. 79-187, § 4, at 726, Laws of Fla.; see Bd. of Cty. Comm’rs v. Colby, supra note 31. The state government’s role in setting records charges has since been eliminated and replaced with the requirement that fees be based on the salary rate of the personnel actually reviewing the record request. Ch. 81-245, § 1, at 989, Laws of Fla.; Ch. 84-298, § 5, at 1401, Laws of Fla.

- 44Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 15.234 (2020).

- 45Md. General Provisions Code Ann. § 4-206 (2020).

- 46See, e.g., N. H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 91-A:4 (2020).

- 47See, e.g., Minn. Stat. Ann. § 13.03 (West 2019).

- 48See, e.g., N.Y. Pub. Off. Law § 87; See also Haw. Code R. § 2-71-1 (LexisNexis 2020).

- 49Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), 5 U.S.C. § 552 (2018).

- 505 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(A)(i). OMB has found that they only have authority to establish guidelines for charging fees and not when they should be reduced or waived. Beyond the plain statutory language outlined below, this authority is agency-specific. See Freedom of Information Reform Act of 1986, Pub. L. No. 99-570, §§ 1802-1804, 100 Stat. 3207, 3248-50 (1986); FOIA Fee Guidelines, 52 Fed. Reg. 10,012, 10,016 (Mar. 27, 1987). For OMB’s uniform fee schedule and guidelines, see id. at 10,017.

- 515 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(A)(ii).

- 52Id. § 552(a)(4)(A)(ii)(II).

- 53Id. § 552(a)(4)(A)(iv)(II).

- 54See City of Miami Administrative Policy, APM-4-11, at 5 (Feb. 2, 2015), available at http://archive.miamigov.com/employeerel/pages/CityAdminPolicies/APM/APM%204-11%20Public%20Records.pdf.

- 555 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(A)(iii).

- 5632 C.F.R. § 286.12(l)(1) (2020).

- 57Id. §§ 286.12(l)(2)(i)-(iii).

- 58We selected FOIA as a model because: (1) it is a process that is broadly understood across the country and (2) it most directly serves the public interest. As will be discussed in the next section, it is also less likely to burden government records custodians.

- 59See 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(A)(iii).

- 60See, e.g., Fees Charged to the Public for Examining and Duplicating Records, Miami-Dade County Administrative Order No. 4-48 (July, 24, 1990), http://www.miamidade.gov/aopdfdoc/aopdf/pdffiles/AO4-48.pdf (further defining county public records policies regarding fees charged to requesters).

- 61Interview with LA City Clerk’s Office (on file with authors).

- 62Fla. Stat. § 119.01(1) (2020) (emphasis added).

- 63We chose these five cities because: (1) they are among the ten most populous cities in Florida and (2) they use software to track their public records requests, making it possible for us to obtain and review their request logs. It is worth noting that not every local government uses such software.

- 64Note that Figure 2 is an average of the results for each category across the five Florida cities listed above. The mean rates of records requests per category are presented to illustrate how frequently certain community segments seek government documents. The averages in this figure are not weighted by municipal population size nor are they intended to predict specific outcomes. Instead, they are intended to help guide policy discussion surrounding the feasibility of waiving records fees for requests submitted by public interest entities.

- 65The percentages displayed in the pie charts are rounded up to the nearest tenth of a percent for the sake of simplicity.

- 66The log we received is maintained by the Miami City Attorney’s Office on behalf of all city departments and does include many requests for police records. Similarly, the log we received from Tallahassee is maintained by city hall but does not include direct requests made on the police department.

- 67The relative size of the Individual or Uncoded category is a rough, but imperfect, indicator of the quality of data we received. Cities with a larger percentage of Individual or Uncoded category requests typically included less information in their logs.

- 68Again, this analysis only speaks to the number of requests made and not the amount of government labor required to respond to any individual request. Note also that Figure 9 is an average of the results for each category across the five Florida cities surveyed in this Article. As with Figure 2, it is not weighted by municipal population size nor is it intended to predict specific outcomes. Instead, the averages are intended to help guide policy discussion surrounding the feasibility of fee waivers for public interest entities.